It’s late one Saturday night and the Mall, one of the oldest shopping centres in Nairobi’s Westlands district, is deceptively quiet, a stark contrast to the busy streets outside. But walk down one flight of stairs and the dimly lit basement is teeming with life as bodies pulsate to the heady rhythms of jungle, dancehall, UK funky, and South African gqom and amapiano. The Mist – the kind of underground club where you can catch anything from grime to glitch, and the resident DJ takes to spinning Pharoah Sanders at 4am – is hosting nu.wav, an event organised by recent graduates of Santuri Electronic Music Academy’s DJing 101 programme. Course mates and clubbers surround the decks, dancing and cheering loudly as each person finishes their set.

Santuri Electronic Music Academy (SEMA) is the educational arm of Santuri East Africa, a Nairobi-based platform that supports east African music producers, DJs, sound engineers and other music industry professionals. SEMA runs courses in both music production and DJing, and the focus is placed on creating community and culture as much as it is on technical skills. Students learn how to ethically interact with traditional music, and are encouraged to engage with topics around identity, class and gender. Out of the 150 students that have been trained by SEMA over the past two years, 55% have been non-male, with the balance tipping even further in recent courses.

“It was really cool to have a female-heavy cohort” says Marion Muthiani, a recent SEMA graduate who DJs under the name nowisgood. “Santuri is a welcoming space so we feel comfortable in the classes and events.”

Self-described “ethnomusicology nerd” Nabalayo joined SEMA’s advanced music production course as an accomplished artist, having already self-produced her 2020 debut Changanya, a sublime exploration of Kenyan folklore and Nairobian life. “Before I would call myself a singer masquerading as a producer, but after [the SEMA course] I felt validated and confident in what I’m doing,” says Nabalayo. The course gave her the confidence to mix and master her new album IPO, as well as singing, playing, and producing every part of it.

Most of Santuri’s current activities are based on findings from a 2020 report conducted in partnership with Ableton. The research, carried out by Kenyan artists and Santuri associates KMRU and Coco Em, found that lack of equipment and community spaces were major barriers in the industry, and that female and queer artists felt unwelcome in most music spaces. Armed with this knowledge and some funding from the Goethe Institut, Santuri launched the Electronic Music Academy in 2021 with a specific focus on these areas.

Santuri had been active on and off since 2013, when its co-founders, Kenyan DJ and cultural activist Gregg Tendwa and British DJ David Tinning, began organising one-off events at festivals around east Africa. These sessions birthed a couple of great records, like Esa and Auntie Flo’s The Highlife World Series and On the Corner’s Nyako, but the team quickly understood the need for longer-term, more locally impactful projects. Their first step was to support Femme Electronic, a platform started in Kampala by DJ Rachael to train female DJs and producers.

Kampire, a core member of Kampala’s Nyege Nyege collective, who has played clubs and festivals across the world with her eclectic and bass-heavy sets, remembers attending some of those early workshops: “It was back in 2016 so I had really just been DJing for a few months at that point,” she recalls. “It was valuable for me to get into the technicalities and history of DJing, but it also introduced me to the idea that so much of DJing and electronic music is about organising around community, and that it is important for women and queer people to organise, because men are mentoring each other and booking each other.”

Spearheaded by Justin Doucet (AKA DJ Huilly Huile) and supported by Santuri, Femme Electronic launched in Nairobi in 2017, and several people who were involved back then are involved with Santuri to this day. Among them is Coco Em, who is a SEMA tutor and who is quickly becoming a fixture on dancefloors across the world (including gigs at Boiler Room and London’s Fabric) with her sets that move between Afro house, kuduro, and Kenyan gengetone.

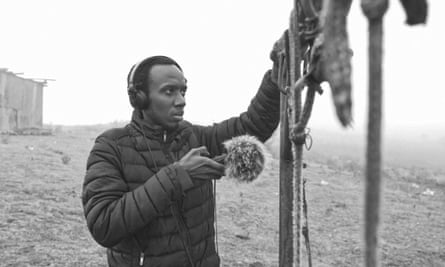

Renowned sound artist KMRU was also accepted into the Femme Electronic programme as he was too young to sign up to other DJ schools. “This was the time in my music journey that I wanted to start playing live, I was really trying to find a performative side to my music” he says. KMRU is quick to acknowledge Santuri’s contribution to the Kenyan music scene over the past few years: “New artists are getting access to equipment and software, and they’re sharing knowledge about production and music-making. There is so much potential, I’m curious to see how it’s going to evolve.”

As well as taking part in the Femme Electronic DJing courses, KMRU offered to informally teach production at a time when Santuri was running workshops with “no funding and none of our own equipment”, says Doucet, who now works full-time with Santuri. To ensure the workshops were accessible to everyone, the team would offer lunch and transport. “We found that as soon as we catered for that and had a good internet connection it was really easy, people learned a lot and made their first beats on Ableton. That was the first iteration of SEMA.”

For KMRU the experience planted the seed for the Nairobi Ableton User Group, an organisation he co-founded that offers Nairobi-based musicians who use Ableton a space to meet, learn, and support each other that has since scaled back its activities. “KMRU is hailed as a bit of a hero and has helped foster a culture of experimentation,” says Tinning. “His commitment to the community has been huge.” Even since moving to Berlin, KMRU has continued to share his processes in SEMA masterclasses and panels on experimental music, as has Kenyan composer Nyokabi Kariũki.

after newsletter promotion

“When Santuri first started doing workshops nine years ago, we relied on a lot of artists and educators coming from Europe, the UK or South Africa,” says Tinning. “Now we are really happy that all our teaching team are east African, and only a few guest tutors or specialists are involved from outside the region. We’ve focused on building the skills of our tutors so the knowledge – and how to share it – resides in east Africa.”

Santuri connects students to the local scene through a series of events, and to the rest of the world through their Santuri Signal show on Accra-based Oroko Radio. The events are key, says Doucet. “Instead of the students graduating and waiting to be picked up by some festival or club night, they often get their first performance opportunities directly from us, surrounded by their friends and peers.” By fostering an inclusive music scene, Santuri is slowly dismantling barriers in the industry: “I’ve never seen a community where there are so many female sound engineers, producers, and DJs. We are front and centre,” says DJ Shock, who is both a DJ tutor and a production student in SEMA.

“Platforms like Santuri are very important, particularly in east Africa,” agrees Kampire. “One thing I’ve learned about DJing is that it’s never just about you as an artist, it’s also about the scene you come from and the sounds you represent. Literally, I’m not winning unless all of us are winning.”