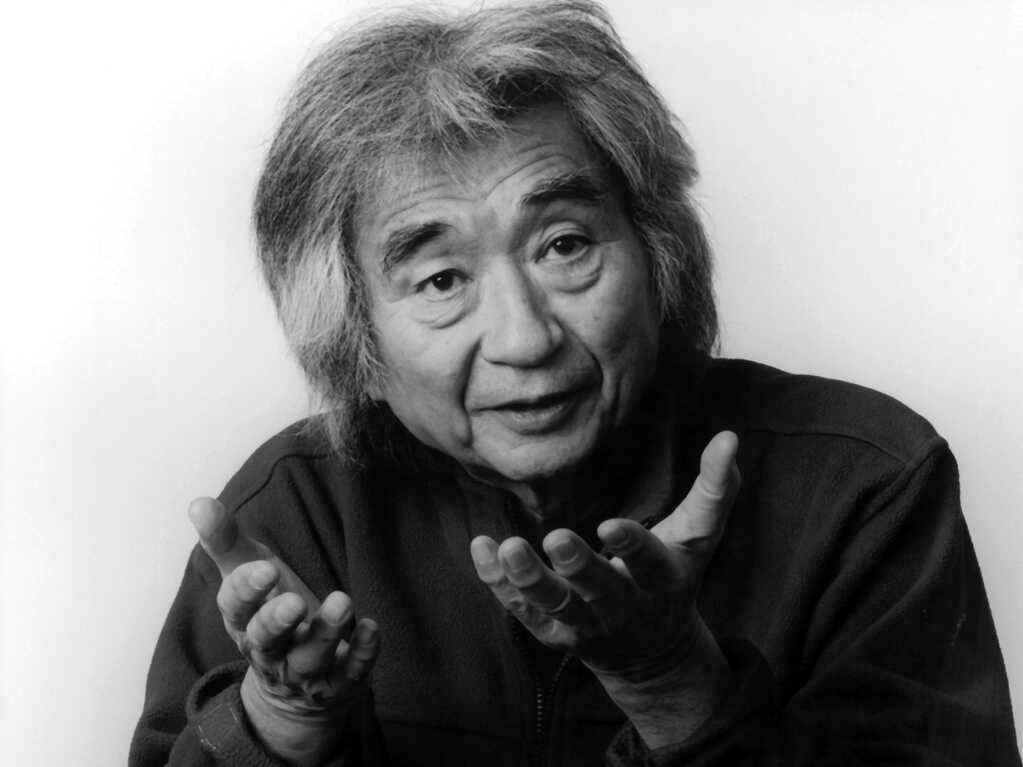

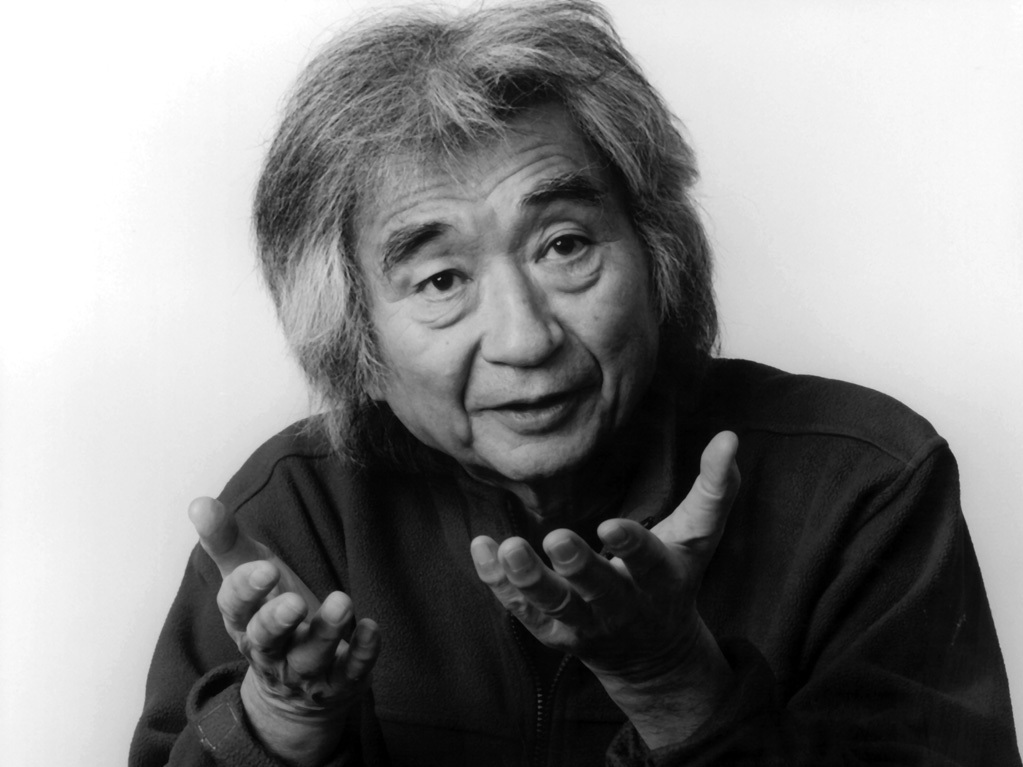

Seiji Ozawa led the Boston Symphony orchestra for nearly 30 years.

Boston Symphony Orchestra

hide caption

toggle caption

Boston Symphony Orchestra

Seiji Ozawa led the Boston Symphony orchestra for nearly 30 years.

Boston Symphony Orchestra

Seiji Ozawa, the conductor who led the Boston Symphony Orchestra longer than any other music director, has died at age 88.

The conductor died Feb. 6 in Tokyo, according to a statement by the Seiji Ozawa International Academy Switzerland.

In his Boston career, which spanned nearly three decades, he was a both a celebrated and controversial figure. When Ozawa arrived to lead the BSO in 1973, he was different from the start. Longtime classical critic Ellen Pfeifer remembers how the then 38-year-old conductor often wore a tunic at the podium, rather than a tux. He had a moptop head of hair and hanging around his neck were love beads.

“He was very much a product of that era,” Pfeifer says.

Ozawa’s older predecessors had names like Leinsdorf, Steinberg, Munch, Koussevitsky. Choosing a thirty-something Asian was a bold move for the BSO.

“They went out on a limb,” Pfeifer says.

Ozawa’s rise paved the way for other Asians to break into a genre dominated for centuries by white men. This cultural sea change wasn’t lost on the maestro either, as Ozawa told NPR in 2002.

“Since I’m kind of a pioneer I must do my best before I die, so people younger than me think, ‘Oh, that is possible. I think it’s possible, I hope it’s possible.‘” Ozawa said.

Ozawa conducts the Boston Symphony Orchestra, with soloist Yo-Yo Ma, in Prague.

YouTube

In Japan, Ozawa’s father was a country dentist who — as the story goes — pulled a piano 25 miles in a wagon so his son would have an instrument to play. But as a teenager, Ozawa sprained a finger playing rugby, so he turned to conducting. In 1959, he took the top prize at the International Competition of Orchestra Conductors in Besançon, France, which caught the attention of then BSO music director Charles Munch. Later, Leonard Bernstein took notice and gave Ozawa a job at the New York Philharmonic. After stints in Japan, Toronto and San Francisco, Ozawa won the position of music director for the Boston Symphony Orchestra. And there he stayed for 29 years.

Ozawa conducted massive symphonies from memory. He didn’t always use a baton and his body swayed on the podium.

“What a dancer he was!” longtime BSO trombonist Norman Bolter says. He played just feet away from Ozawa from 1975 to 2002 — nearly the entire duration of Ozawa’s time with the orchestra.

“But not only just a dancer getting up there and doing his own jig,” Bolter recalls. “His clarity in conducting was extraordinary, but it just wasn’t this persnickety, trying-to-be-clean detail. It had a fluidity, it had a ballet aspect to it, and it was alive.”

Ozawa was also fun. In 1988, he led the All-Animal Orchestra on “Sesame Street” and in 1963 he was a guest on the TV show “What’s My Line?”

Sesame Street

YouTube

Bolter says Ozawa’s grasp of certain composers was profound.

“Seiji did Bartók, in my mind, like nobody did. I mean he just had this unbridled fervor that would go over him with Bartók and certain other pieces,” Bolter says. “He let the orchestra play; he wasn’t a control freak in that way.“

But a string of controversial personnel decisions enraged longtime BSO administrators and musicians in the mid-1990s, leading to resignations, bad press and a precipitous drop in morale.

Even so, Pfiefer says Ozawa changed the face of the orchestra and was something of a musical ambassador. He took the BSO to China, making it the first U.S. cultural organization to do so after relations with the country were normalized. At Tanglewood, the summer home of the BSO, a new hall was named after Ozawa in 1994.

During his Boston tenure, Ozawa never forgot his native Japan. There, he founded the Saito Kinen Orchestra in 1984 and the Saito Kinen Music Festival seven years later. In November, 2022, the 87-year-old conductor led the orchestra from a wheelchair in Beethoven’s Egmont Overture, the first time a live symphonic performance was beamed to the International Space Station.

Ozawa left the BSO in 2002 to lead the Vienna State Opera. But fans could still hear the maestro in Boston — not at the podium, but at Fenway Park, egging on his favorite baseball team.