Brandon Deener, former producer for hip-hop and R&B royalty such as Timbaland, Missy Elliot and Lil Wayne, wears the multi-hyphenate badge well. He’s now known more as a visual artist and musician among other titles, dedicated to painting the Black community and carving its people a place in modern history by illustrating both boundless beauty and agency.

It’s been nine years in the making and now Deener is bringing his third solo exhibition, In Unison, to Adam Cohen’s A Hug from the Art World in Manhattan, New York, where the Guardian is introduced to him. Last year, Brandon was behind two solo exhibitions in Los Angeles where he and his studio reside – Children of the Sun, Sol Searchin’ at Simchowitz Gallery in West Hollywood and Inward at the Jac Forbes Gallery in Malibu. With music still guiding his work, Deener also offers The Sound of Unison as his debut to the world as a leading musician and as a formal wedding of his music to his visual art.

Deener credits many of his achievements to a star-studded team who supports him. Managed by Jaha Johnson and mentored by art industry legends and collectors, with particular emphasis on Stefan Simchowitz and Tony Shafrazi, who has partnered with Keith Haring, Jean Michel-Basquiat, Andy Warhol and David LaChapelle, and the estate of Francis Bacon, Deener urges the importance of having a team, stating, “It is as important as the artwork we create.”

Deener defines himself as an Afrofuturist artist. Afrofuturism is a genre rooted in the explicit intersection of science fiction, technology, innovation, and Black and African mysticism and Black history across art, film, literature and music. It is more commonly regarded for its “dystopian” essence from Octavia Butler’s Kindred as genre-defining literature. In the past decade, Afrofuturism has witnessed a swift rise to mainstream films and television with Ryan Coogler and Joe Robert Cole’s adaptation of Black Panther achieving worldwide success. When asked what it means to contribute to the genre, he says, “It means to manifest and see what you bring into fruition, realizing that higher power … and as a creator not bound by time, I want to look at us as a people of every time – past, present and future.”

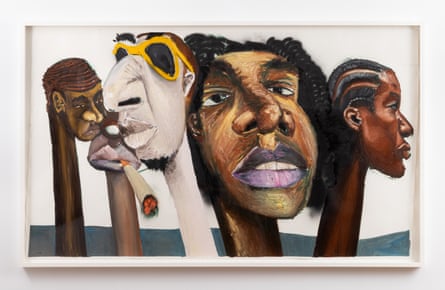

Through his painted visions of Black pride as they exist and should continue to exist, Deener realizes that higher power. Black pride is represented through spray-painted, acrylic-painted, and oil stick-applied long necks, large and exaggerated lips, and personified noses. In explaining why he illustrates noses the way he does Deener says: “It’s about self-love … just to show how prominent our features are, and that no matter what color they are, that’s a Black nose, that’s a Black person.” He uses somewhat incomplete dimension-bending backgrounds, hovering classic cars, inventions offering freedom of exploration and discovery. I asked if he was ever worried about his works being criticized or used against him and Black people to reclaim the stereotypes that whiteness has projected through its labor of minstrelsy and colonial history. “No,” he said. “I am very true to being very unapologetically Black in my work. Given the history of Blackness and art and the lack thereof being represented and represented in the work, I have a duty or dedication to depicting us, always.”

The Sound of Unison complements In Unison as its theme music, a timeless body of 10 tracks including familial words of affirmation in Brand New Brandon, loving Yoruba chants in Mo Ni Ife, and pensive pendulums in Ridgeway. The Sound of Unison does its job in bending time and not clinging to one music category, but clinging to undying soul and spirit.

At the opening reception, Deener explained in reference to his artwork, “There is music in the faces.” He listens to 1960s improvisational jazz, preferably sounds and rhythms of Miles Davis, Herbie Hancock and Fela Kuti to inform his style and guide his creative process. He relates the oneness of improvisational jazz musicians playing together to his mixed media approach, trusting his own experimentation.

When asked what it means to contribute to the Afrofuturism genre, Deener states he “had no idea that art was going to happen for me … at all”. The South Memphis native was born into and raised in the church by a spiritually and musically gifted family. Although an only child raised by a single mother, Deener was not alone. Surrounding him was also his uncle, a bishop who plays the drums, and cousins who all can sing. “Everything was all music,” Deener reveals, and so much so that he unintentionally summons the spirit, energy and likeness of his ancestors through his work. “I have depicted ancestors unbeknownst to me. One of the figures in Summoned by Hickory Smoke, the figure driving the car, reminds me of my great-grandad. It looks like him.” This despite him confessing to having only one memory of him. Deener’s genesis as an Afrofuturist artist comes from his past and South Memphis as an anchor, which he left in 2007. He channels the melodies and improvisation of life’s journey for Black people to project an Afrofuturist world.

Despite producing some of hip-hop’s biggest artists, Deener reveals he “… played small, being a fly on the wall and often got overlooked”. After experiencing a stale start to his creative career in Miami, the dream of being an artistwaned and depression sank in. “I used to be a negative thinker, and a lot of this stuff is passed down from generations … We speak negativity on ourselves and repel blessings or postpone them. I was speaking against what I was trying to manifest … I was in search of a relationship with God.”

After much maturation through self-love, meditation, prayer and getting rid of “a problem-based mindset for solution-based mindset” since his music producing days, Deener refuses to “hide his blessings” and shares his God-given talent with the world through his artwork and music. In a humorous outburst he shares, “I once cleaned the toilets! I went from cleaning the toilets in Timbaland’s studio in Virginia to now Timbaland owning my work.” Timbaland does not just own one of Brandon’s works; he owns four of them.