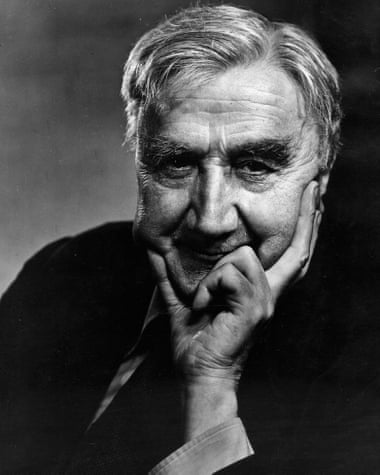

When Steve Roud was young, he began collecting records. Hardly unusual for a child of the 1950s – but this boy from south London was different. Not content with just listening to LPs, Roud began indexing them – his own and ones he found mentioned in newspapers and magazines. He used old shoe boxes as a primitive filing system and wrote the titles on 5×3 inch record cards that his mum bought him once a week. He soon realised his hobby was turning into something more. “Without knowing it,” he says, “I was becoming a librarian.”

Soon enough, Roud would become one for real, working much of his career for the London borough of Croydon. His infatuation with indexing would persist too, those shoe boxes finally swelling into something remarkable. Even as a teenager, Roud had been fascinated by folk music – how across the centuries, dozens of voices could send songs shooting countless different ways, their titles and lyrics shifting even as their cores remained the same. As he grew up, armed with proper training and new technology, Roud took to collating this bounty in earnest, hunting down leads and developing an elegant method to trace a song’s heritage.

The result, the product of 52 years of effort, is the Roud Folk Song Index. Including hundreds of thousands of references to tens of thousands of songs, Roud’s work spans the anglophone oral tradition, taking in English villages, Appalachian hilltops and harbours in the Caribbean. The index has become indispensable for folk fans worldwide, bolstering genealogy projects and inspiring musicians. In its size and ambition, Roud’s project speaks to the challenges of constraining such a varied tradition – and even to deciding what folk music actually is.

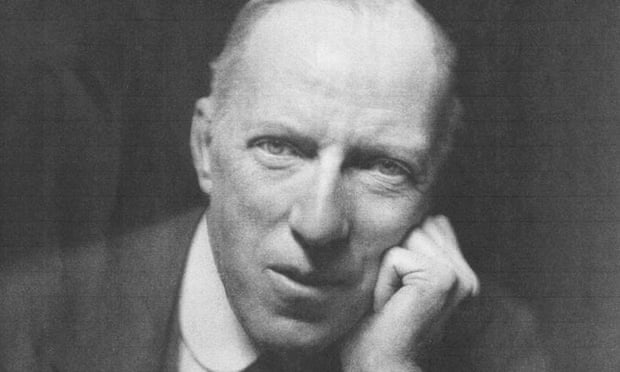

People have systematically collected traditional English music for more than a century. In the years before the first world war, enthusiasts such as Ralph Vaughan Williams and Cecil Sharp scoured country lanes and village inns for people to record, worried that industrialisation and urban life would soon wash traditional tunes away. Musicians both, Williams and Sharp also wanted folk melodies to inform English classical music, just as Sibelius did in Finland or Antonín Dvořák in Bohemia. Visiting King’s Lynn, in 1905, Vaughan Williams spent time at the Tilden Smith, a pub where local fishers were sheltering from January storms. The songs Vaughan Williams heard there may have influenced some of his most famous compositions, appropriate for a man who once called music “the expression of the soul of a nation”. These early English collectors, for their part, were shadowed by colleagues across Britain and Ireland, and in the New World.

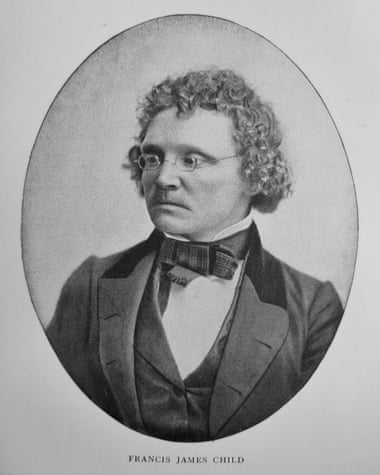

Up to a point, the Roud Folk Song Index fits into this older tradition. For one thing, it incorporates the efforts of Francis James Child, an American collector who amassed more than 300 ballads in the late 19th century. But in vital ways, Roud’s work is different. Unlike earlier collectors, he dispassionately notes songs referenced in other sources. When possible, he provides digital scans of song sheets, avoiding the habit of purging lyrics that older collectors considered rude or inappropriate. But speak to experts in the field and what really makes Roud’s index special is its colossal scale. “It’s huge,” says Dr Fay Hield, a folk musician and ethnomusicologist at the University of Sheffield. Roud himself says his database now boasts about 25,000 tunes, painstakingly gathered from newspaper archives, magazines and songbooks, to say nothing of past collectors and fellow “nerds” online.

Spend time exploring Roud’s index and this scale can be almost overwhelming. There are war songs and love songs and songs about cattle and mining and bar-room cheats in the East End. There are songs about Bonnie Prince Charlie, and finding solace in death, and one, Hares on the Mountain, where the singer decides to forget male advances and “attend to my schooling” instead. This thematic spread is matched by geography. Between migration and colonisation, slavery and settlement, anglophone culture has swept the planet. Variations of one song, The Lowlands of Holland, were once known at Axford in Hampshire, Perth in Scotland, and across the Atlantic in Maine and Tennessee, alongside dozens of other places. It’s harder to know how old these songs actually are – the best Roud can do is tell us when they were first jotted down or printed, something rather different – but here too his index is vast in scope. One of the older tunes in the index was first mentioned by Samuel Pepys in 1666, while most were put down in the 19th century.

Beyond the songs themselves, meanwhile, Roud’s index is impressive for its system of references. Transmitted orally, or else learned from ephemeral printed sheets called “broadsides”, folk songs are often hard to track back to a single source (Roud maintains a separate Broadside Index as part of his larger folk song index). To explain what he means, Roud gives the example of Gypsy Laddie, a song with about 500 different versions and 100 titles. As Roud laconically puts it, this could make grasping how tunes interacted “quite chaotic”. But by grouping songs together through so-called “Roud numbers” – each one encompassing every variation on a particular tune – he makes it easy to find and compare dozens of Gypsy Laddies at once. As Tiffany Hore of the Vaughan Williams Memorial Library says, that helps researchers answer a torrent of important questions (the VWML also hosts the index on its website). Among other things, adds Hore, that includes how different musical cultures intermingled, or how songs changed over time.

Not that Roud’s influence is simply down to his talent for record-keeping. He has battled to spread his index’s popularity, running workshops and attending conferences. He’s never been paid for his indexing, except to cover expenses, and his home has become a fortress of documents and books. But perhaps the most telling example of Roud’s dedication came when he started digitising his index in the 1980s. Eager to share his hobby, he began posting floppy disks, sometimes 20 at a time, to subscribers around the world. From there, Roud recalls he spent hours on the phone, helping muddled (and often elderly) fans work his database on hulking Commodore computers. “I did think it was important,” he says of his efforts. “When you’re in a small field like ours, you do tend to be cooperative, because you’re either that way or at each other’s throats.”

Hore is more direct: “It’s his whole life, really.”

If the Roud Folk Song Index is the most ambitious project in traditional music, Sing Yonder might be a close second. The brainchild of Karl Sinfield, an amateur folk musician and graphic designer, it aims to take every song in Roud’s database and give it context. Offering potted histories of performances and suggestions on setting notes, Sinfield says he wants Sing Yonder to make the index “more approachable, more accessible”. He jokes that at his current pace it’ll take him 630 years to get through every song on the list – but he’s hardly the first to be seduced by the vastness of Roud’s database. For if professional researchers now take the index almost as gospel, habitually quoting the Roud number whenever they reference a song, others are tugging Roud’s work far beyond the academy.

For starters, the University of Sheffield’s Hield explains how she uses Roud numbers to craft her own arrangements of songs, borrowing lyrics from multiple versions. Then there’s its rising influence in genealogy. As Roud puts it: “I get letters from people saying, ‘I’ve found my great-grandad’s name in your index, tell me what you know!’” As he admits, that often isn’t much. But since his database started adding audio recordings of songs, Roud can increasingly offer people crackly renditions by long-lost ancestors. He is anxious to reflect modern concerns in other ways, such as adding a feature to search songs by location. Working with colleagues, Roud has also started organising ballads by subject – a boon given around half the requests he receives are on specific topics such as poaching or the harvest.

Not that Roud would ever claim that his database is perfect – or even perfectable. To a large degree, that’s down to the project’s sprawling nature. Cobbled together over the span of two generations, Roud has come too far to start again from scratch. In practice, that makes certain tweaks, such as categorising songs by the race of the singer, incredibly challenging. That’s doubly true, Roud adds, given that many early collectors ignored or actively disdained these very questions. In Britain, most people were white until the mid-20th century, and while on a trip to Appalachia, Cecil Sharp shunned ballads sung by African Americans.

Some in the folk community have worries about exactly what gets added to Roud’s index. Roud himself offers a simplified explanation: “Songs sung informally by ordinary people, by their own volition, in their everyday lives, and passed on from person to person and down the generations.” But Hield fears that Roud’s work overlooks everything the folk tradition has to offer. Should new folk songs, she ponders, receive their own Roud numbers? What about dramatic reworkings of old favourites?

Of course, none of this is unique to Roud’s index. Arguments about what constitutes folk music have grumbled on for decades. Roud speaks for the field at large when he says that deciding what makes it into his index is a “very knotty” question. But if he has some limits – for instance rejecting contemporary folk compositions on the grounds that they’re not performed spontaneously – Roud does seem to have a broadly catholic attitude towards his database. “If Harry Cox had sung Yellow Submarine then it would have to go in,” is how he puts it, partnering the Norfolk farmhand and folk giant with the Beatles’ classic. In a similar vein, Roud happily includes songs ignored by the likes of Cecil Sharp, including Jamaican ballads, and music hall ditties that kept being sung after the curtain fell. The point, he emphasises, is less a song itself and more the tradition that grows up around it.

Some of Roud’s judgments do feel subjective. But perhaps that’s inevitable given the notorious malleability of the genre in general. As Louis Armstrong is rumoured to have put it: “All music is folk music. I ain’t never heard a horse sing a song.” Hore agrees. “It’s very hard to say what a folk song is nowadays,” she suggests, adding that even a pop hit like Sweet Caroline could plausibly claim the title given its oral popularity since England’s recent Euro 2022 victory.

As a self-proclaimed historian, however, Roud seems content sticking to the music of times gone by. At the same time, he stresses that he is constrained by what he can find in archives, noting, for instance, that few early collectors were interested in the music of immigrants. Beyond these tussles over definition and delineation, moreover, you get the sense that Roud would be buried under the weight of his index if he tried to grow it further. “I’ve got to stop somewhere,” he says of the idea of indexing modern folk performers. “I’m waiting for somebody else to do that – some other idiot like me to come along! But then they’ll have the problem of defining what folk is. It’s even worse now than it used to be.”

Yet even if the Roud Folk Song Index can’t offer a dictionary definition of folk music, everyone I spoke to still considers it a highly valuable resource. As well as its enormous breadth, it’s true in how its songs continue to evoke universal themes. Few women would nowadays disguise themselves as men and sneak aboard their lover’s battleship, as in Jack Munro (Johnny’s Gone A-Sailing). But as Hield explains, that hasn’t stopped some in today’s queer community from “trying to find themselves” in these very tunes.

Hore makes a similar point, suggesting that songs about love or loss are never going to age, even if the lyrics risk sounding antique to modern ears: “They speak about what it is to be human.” That feels like a fair summary of Roud’s project as a whole. Meanwhile, the man himself keeps working in his 73rd year, and his battered shoe boxes slowly gather dust.