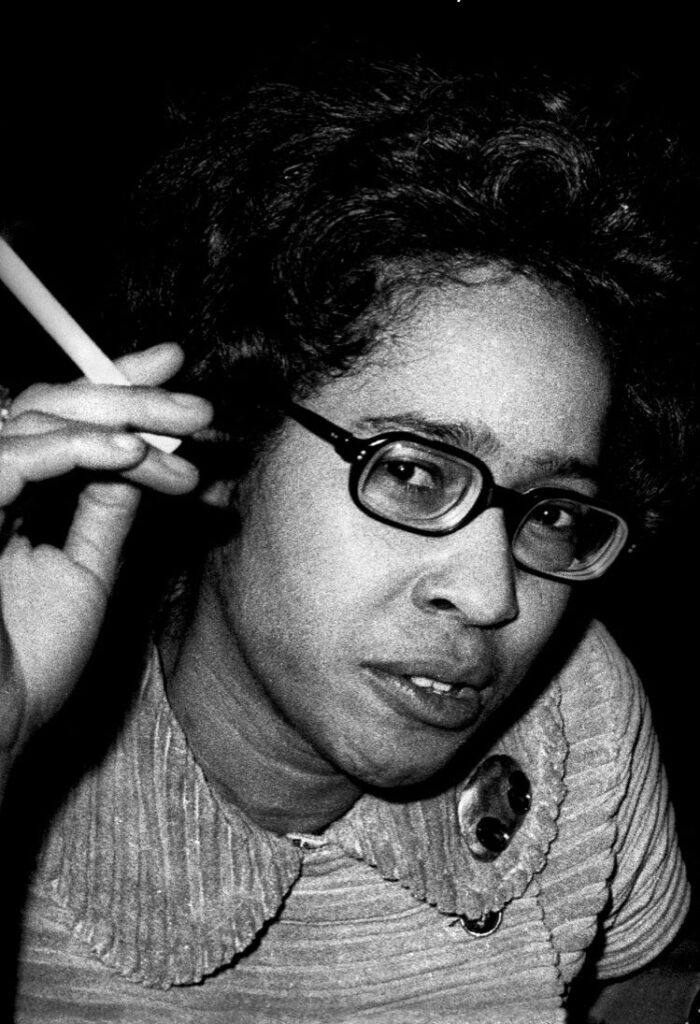

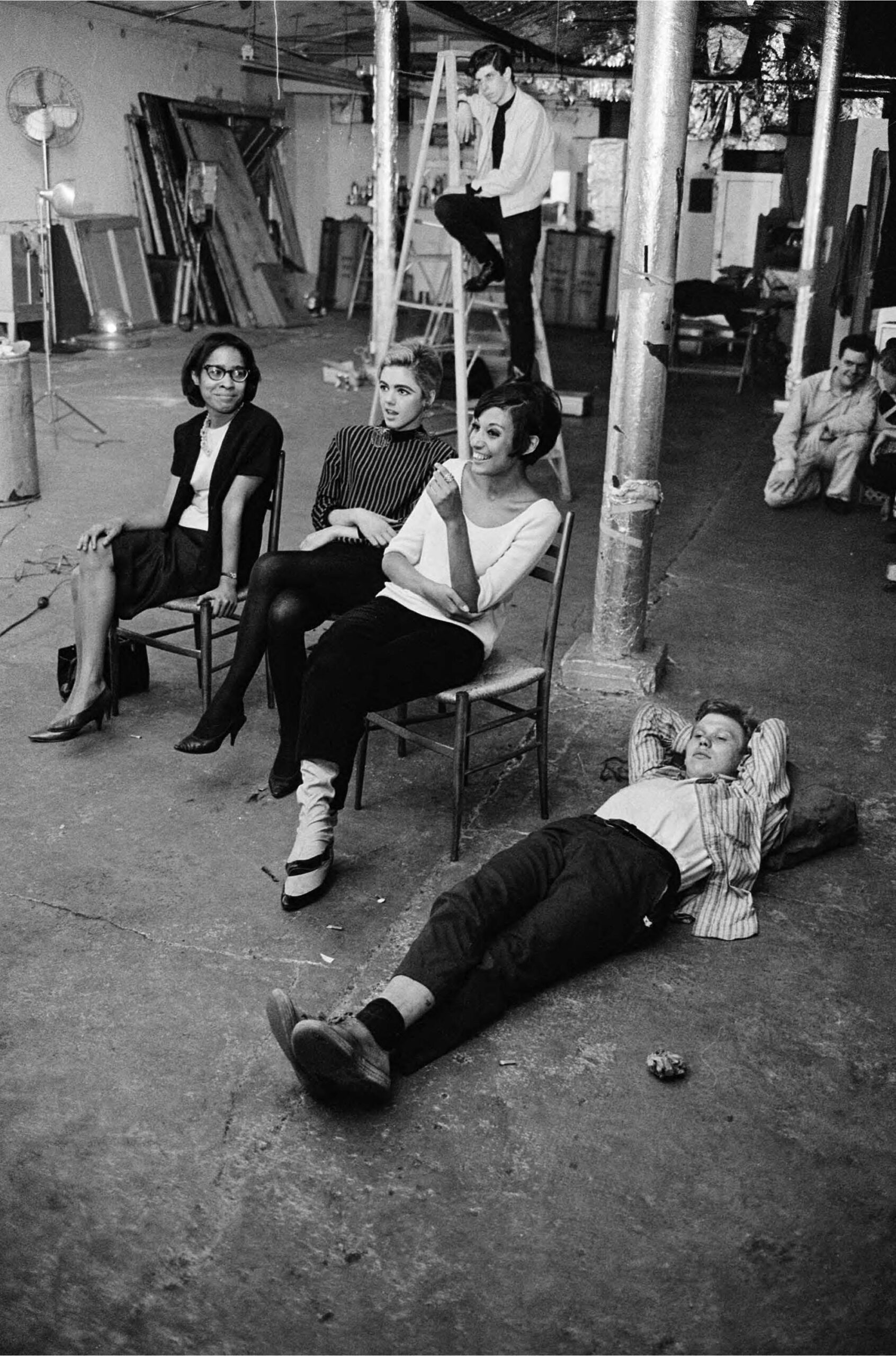

In the universe of Andy Warhol’s Factory, we typically name-check the requisite cast of characters: Jane Holzer, Edie Segdwick, Candy Darling. But one woman, Dorothy Dean, remains relatively unknown. A writer, socialite, Harvard graduate, Warhol actress, and freelance copy editor, Dean’s biting humor and whip-smart intelligence was mostly lost to the annals of history.

But now, Anaïs Ngbanzo, the Parisian publisher and editor, wants to remedy the oversight. Debuting this month, her new book Who Are You Dorothy Dean? is a compilation of Dean’s correspondences with Warhol figures, unpublished newsletter of film reviews called the “All-Lavender Cinema Courier,” and original essays by Emily Wells and Ara Osterweil. “I was so surprised that I’d never heard about her before because I’ve read a lot about artists and personas of Warhol’s Factory,” Ngbanzo says. Dean flitted between jobs as the first female fact checker at The New Yorker and the tough-as-nails bouncer of Max’s Kansas City. In Just Kids, Patti Smith calls her “small, black and brilliant,” recounting how she “stood before the entrance to the back room like an Abyssinian priest guarding the Ark.” Her sharp tongue followed her everywhere: in her starring role in Warhol’s film My Hustler, (1965), Dean says to Warhol superstar Paul America: “You are very pretty but you are not exactly literate.”

On the eve of Ngbanzo’s debut of Dorothy, a play written and directed by the polymath that premiered at the ICA in London for a special one-night performance earlier this week, we connected to talk about correcting Hilton Als’ critical portrayal of Dean in The Women, the plight of being brilliant but lazy, and leaving the gossip out of a book on a legendary gossip.

———

DALYA BENOR: Hi Anais, thank you so much for talking with me about the book and Dorothy Dean. It was so nice to read it.

ANAÏS NGBANZO: Did you like the book?

BENOR: Yeah, I loved it. I was not only blown away by Dorothy and her writing, but also her as a figure, and how much she resonates with contemporary society. How did it all begin?

NGBANZO: The first time I read about her was in The Women [by Hilton Als]. It was summer in Paris and I remember going to the bookstore. I was so surprised that I’d never heard about her before because I’ve read a lot about artists and personas of Warhol’s Factory. She made a strong impression on me when I read this essay. I launched my press [Éditions 1989] three years later and I was researching what to publish next. I found out that NYU was holding Dean’s archive. I went to NY to go through them. It was a very emotional period for me. I was releasing a film documentary about another artist, Julius Eastman, and going through the archive during that same time was quite intense. But after 2 days going through the boxes, I knew I was doing something right by publishing this book.

BENOR: Were there any stories about her that you connected with?

NGBANZO: I think what hit closest to home was the fact that she was a Black woman evolving in an experimental scene. I was also quite intrigued and surprised by her social standing in New York. The artists, poets and musicians she was friends with, are people I’ve been listening to and reading since a very young age.

BENOR: Reading the New Yorker article that Hilton Als wrote, and seeing how she had a very moralistic view of the world and really decided whether she liked someone or didn’t, I really related to that. I think we both have that sensibility.

NGBANZO: Exactly. This is something I related to.

BENOR: Do you know how she first met Andy Warhol and solidified her place in the Factory scene?

NGBANZO: I wish, but this part remains unclear.

BENOR: A while ago, I think I asked how you decided what to include in the book and you said you chose materials that weren’t too personal to Dorothy. What were those personal materials, and why didn’t you put them in?

NGBANZO: I didn’t include the correspondence with Lou Reed, it was too personal I felt. Also, I didn’t want the book to be too gossipy and many letters were mainly gossip so I didn’t include them. I also stayed away from her correspondence with her mother. Every time I would make a decision in terms of editing, I would ask myself, “Is it something she would be happy about?”

BENOR: I think you did a good job of portraying her in a neutral light.

NGBANZO: Thank you. This was the most important thing to me when working on this book. I didn’t want to take any sides. I just wanted to present her and her work.

BENOR: To go back to Warhol and the Factory members, can you describe what her relationship was like with some of the other characters that were around?

NGBANZO: I mean, it’s hard to say because I’ve been in touch with only one artist from that era, the poet Bibbe Hansen and she met her quite late in her life. She couldn’t share much as she had known Dorothy for a short period of time.

BENOR: She had flaws, but she was also insanely brilliant—insanely smart and talented. And she kind of decided to reject all that and be part of downtown New York and the underground scene. Do you know about her time while she was the bouncer at Max’s Kansas City?

NGBANZO: I guess it was just a ‘money-job’ for her in a difficult period of her time, financially. There’s an existing interview of the woman who hired her for this job. I can read you the quote about Dorothy. It’s quite funny. So the [interviewer] asked, “I understand you were the person who hired Dorothy Dean to work at the door at Max’s. How did that come about?” and [Abigail Rosen] said, “So, I tell my incredibly chic gay pals Michael Maslansky and Frank Macfie that I need an assistant. They tell somebody and somebody else tells somebody else and next thing I know, Mickey is groveling at my feet thanking me for Dorothy Dean. I had never met the woman. I had heard that she was a caustic, mean bitchy alcoholic fag hag. Nothing could have been farther from the truth. When we finally met, she was actually warm to me. The big deal about Dorothy and a lot of people like her is that they want to be noticed at all costs. So, she would say outrageous, scintillating, scatological, sexy things – not because she meant them, but because she wanted to be remembered and noticed. She wanted to make sure that people didn’t think she was ordinary. Being ordinary was the cardinal sin in those days.”

BENOR: I love that. Now that you’ve published the book, I hope she’ll come to life in the collective consciousness as one of the important cultural figures of the Sixties. What do you hope that readers will learn from her and her legacy?

NGBANZO: I think Dorothy Dean matters in terms of visual representation, especially in that era and scene.

BENOR: Should we talk about the play?

NGBANZO: As director, my first idea was to make a film, but there’s not enough existing material. Theater work was always something I was interested in. As for now, the play will be a one-time performance only, at ICA [the Institute of Contemporary Arts]. I’ve learned a lot putting together this play and the cast is great! It has been a beautiful experience.

BENOR: How did you envision the letters being integrated into the script?

NGBANZO: It’s a two-act play. The first act is set in London and basically, it’s two friends meeting at a café. One of them is reading Who Are You Dorothy Dean? and the other is intrigued about the book so they start discussing the life of Dean. The second act stages the correspondences with Edie Sedgwick, Rene Ricard and Lisa Robinson.

BENOR: That sounds incredible.

NGBANZO: I can’t wait!