The crack of the bat. The roar of the crowd. The green grass and the brown dirt. These are the sights and sounds that bring joy to baseball fans every April, both in person and on the silver screen. Historically, baseball films are released in the spring to coincide with Opening Day, when even the most deadened fanbase can spare a smidge of romance and optimism. The Bad News Bears, Major League, Field of Dreams, Fever Pitch and 42 were all released in April. This year, there are none to be found, and that’s not a scheduling accident. A baseball film hasn’t had a significant theatrical release – in any month, let alone April – since 2016, when Richard Linklater’s Everybody Wants Some!! landed with a thud at the box office.

It’s a strange phenomenon since movies about other sports are thriving. In March and April, no fewer than four basketball films will be released (Champions, Air, Somewhere in Queens, Sweetwater). Already this year there have been hit movies about the NFL (80 for Brady) and boxing (Creed III). Other 2023 films will tackle wrestling (The Iron Claw), tennis (Challengers), and soccer (Next Goal Wins). The only baseball film on the calendar is The Hill, a faith-friendly true story of a disabled minor leaguer in the 1970s, but it lacks any major stars and is being released in the doldrums of August.

The death of the baseball film might be bewildering to some, but it’s actually consistent with how Hollywood has viewed the genre, as a money-loser that lucked into two boom periods. In the years following 1942’s The Pride of the Yankees, studios approved a series of copycats about major leaguers who overcame various disabilities and challenges. Jimmy Stewart played a pitcher who returns to the mound after having his legs amputated in The Stratton Story, while Ronald Reagan stars as the presidentially named Grover Cleveland Alexander, who battled epilepsy and alcoholism, in The Winning Team. Jackie Robinson played himself in The Jackie Robinson Story, a re-enactment of the season he broke baseball’s color line. William Bendix played the game’s greatest slugger (at the time) in The Babe Ruth Story, one of the worst sports films ever made.

Once the public got their fill of baseball biopics, the genre lay dormant for three decades. There was the occasional hit, like Damn Yankees, Fear Strikes Out or Bang the Drum Slowly. Billy Dee Williams, James Earl Jones and Richard Pryor teamed up for the unfairly forgotten Bingo Long and the Traveling All-Stars and Motor Kings, a 1976 comedy about a group of Negro Leaguers who strike out on their own as a barnstorming team. That same year, The Bad News Bears pioneered the tropes of the underdog sports comedy – including a team of misfits and a reluctant coach – that would be imitated for decades to come.

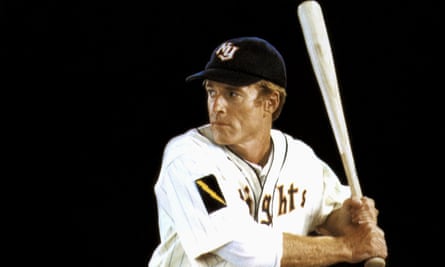

It wasn’t until The Natural, however, that Hollywood once again saw the baseball film as a profitable venture. Based on the Bernard Malamud novel – and notably changing his bleak ending to a more hopeful one – the Robert Redford starrer grossed $48m and was nominated for three Oscars, paving the way for Bull Durham, Major League, Eight Men Out and Field of Dreams, as well as a wave of kids’ baseball movies like The Sandlot, Angels in the Outfield, Rookie of the Year and Little Big League. After that, the baseball film petered out again, and while the last decade produced both a massive hit (Moneyball) and a hidden gem (Sugar), Hollywood seems to have returned to its baseline position of wariness about the genre’s profitability.

Historically, numerous forces conspire to keep the baseball film down. “They’re relatively expensive and skew mostly to men, which limits the audience,” said John Sayles, director of Eight Men Out who has recently ditched Hollywood to write novels. “They’re also about teams, which encourages ensemble casts, while Hollywood prefers to concentrate on one or two bankable stars.” Studios might also be concerned that they don’t play well overseas. Moneyball grossed $34m internationally, largely due to the presence of Brad Pitt, but before that baseball films rarely warranted an international release. Being the national pastime carries with it both benefits and drawbacks.

Recently, new challenges have emerged. In an industry increasingly focused on building cinematic universes, baseball movies aren’t exactly franchisable. The sport itself has been leapfrogged in popularity in the US by basketball and football, making it an even tougher sell to American audiences. Not to mention that baseball itself is suffering from a crisis of confidence. As Major League Baseball institutes new rules seemingly every year – from a pitch clock to an automatic runner in extra innings – it may create some newfound interest in the sport, but it also carries a whiff of desperation. That sort of thing makes studio executives nervous.

It’s for this very reason, however, that Major League Baseball should be on the phone to Hollywood right now, ginning up opportunities for collaboration. “A thriving national pastime requires good movies to support it,” according to Joe Posnanski, an award-winning sports journalist and author of The Baseball 100. “If you asked a casual fan for the 10 greatest moments in baseball history, they’d have Roy Hobbs hitting it into the lights and Kevin Costner playing catch with his dad, or Dottie Hinson dropping the ball. Those moments are more famous in some ways than Kirk Gibson’s World Series home run or the Shot Heard ’Round the World.” Even in this down period, the baseball movie is still what real-life baseball aspires to. That’s why fans continue making videos of their favorite baseball moments set to the score from Moneyball, like last fall’s playoff home run by Bryce Harper or the recent grand slam by Trea Turner in the World Baseball Classic.

Perhaps that’s the path forward for the baseball film. If a key obstacle to its economic viability is the lack of an international audience, the World Baseball Classic could help overcome it. This year’s tournament shattered US attendance and viewing numbers, but its ratings globally were even more impressive. A total of 42.4% of Japanese households watched the WBC Final between Japan and the US, despite the game being shown at 8am on a Wednesday. Japan, of course, is already a baseball country, but the impact in some of the other, less heralded countries – like Australia, Israel, Italy and Great Britain, which won its first ever WBC game this year – could be even greater. Baseball is expected to grow by leaps and bounds in those countries over the next few years, which will naturally create an eager audience for the baseball film.

In fact, let’s make this as simple as possible: what about a baseball film set at the World Baseball Classic? You’ve got all the ingredients. Underdogs and powerhouses. Minor leaguers who may never sniff the majors facing off against superstars. Former players trying their hand at managing. Shocking injuries. Dramatic defections by Cuban players. The opportunities for drama are endless, and the potential benefits to both baseball and Hollywood are limitless. The baseball movie may be in a slump, but, if the game has taught us anything, that’s when you know the magic is about to happen.