Omnes Films has a goal. “Our mission is to fill a void in modern cinema,” says its website. “Our films are passionate, ambitious works made by friends that favor atmosphere over plot and study the many forms of cultural decay in the 21st Century. Whatever the subject or genre, we seek projects that are original in conception and feel like they’ve never been made before.” It sounds wildly ambitious, and maybe it is, but Cannes audiences will be the judge of that when two of its films — Christmas Eve in Miller’s Point by Tyler Taormino and Eephus by Carson Lund — premiere in Directors’ Fortnight.

Taormina and Lund met at college in Boston, where the former was studying screenwriting and the latter film production. Lund, says Taormina, “was always like the crazily prodigious cinematographer. Everyone was very intimidated by this man.” Taormina, meanwhile, wanted to make kids TV (“Like the type I grew up to, the Nickelodeon of the ’90s”). While waiting for a script to sell, Taormina had the idea for a loose indie called Ham on Rye (2019). Lund signed on as DoP, and Omnes was born.

Says Lund, “Omnes is a loose collective that’s becoming tighter. In college I made a short film called Omnes. It’s a sort of a Latin term that’s used often in theater by a director when he needs to get the attention of the cast and crew. And so, we started to tag our films as Omnes Productions. And then we said, ‘You know what? We should make this a real thing.’ So, we rebranded from Omnes Productions to Omnes Films. We wanted to really make it a cinema collective. We’re not an official company, in the sense that we don’t have an LLC or anything. To us, just a symbol of our friendship, our collaboration.”

Christmas Eve in Miller’s Point

Omnes Filmes

First out of the gate was Taormina’s Christmas Eve in Miller’s Point, based on the director’s experience of family gatherings in the early 2000s. “This movie came from many things,” he says, “but I think the genesis was watching my parents’ wedding video on their 30th anniversary. This was some years ago now, and it deeply moved me.”

“I started to revisit some home videos at that time,” he continues, “and I realized pretty quickly that I actually have a total incapability of watching them. I’m too sentimental. It’s too heavy for me to watch my family when we were all so much younger.” That was when the idea of making a Christmas movie came to him. “Once I had that, I knew it would be the way to go. Or, maybe I didn’t know, but I figured that it would be the way that I could reanimate and dwell in the sentimentality that means so much to me.”

Taormina’s film is notable for its striking barrage of kitsch pop classics, which cineastes will recognize from Kenneth Anger’s experimental 1963 film Scorpio Rising. “The option of using Christmas music was just an absolute no. That would’ve been a real cringe-worthy move. But I’m very inspired by Kenneth Anger, very much so, to the point where there’s a central scene in my previous film, Ham on Rye, which was originally conceived and shot to the song he uses in Kustom Kar Kommandos [1965].

“Anger has remained an inciting inspiration for all the work I’ve done so far,” he continues, “and, for this one, Scorpio Rising was there at the beginning. I think we subconsciously realized that this music from the ’60s would make perfect Christmas music, because groups like The Ronettes and so on and so forth went on to make all these famous Christmas songs, so you hear that sound and it immediately feels festive. So, it was kind of a cheat. And on top of that, which ones to choose was very fun for me, because I was actually really interested in how the lyrics of these songs speak so much to the themes of the movie, because the context for a lot of these songs is love and love lost, you know?”

Eephus

Omnes Films

Lund, meanwhile, had been cooking up Eephus, a personal story of his own, about a baseball field that is being demolished to build an elementary school. “We shot Eephus five months before Miller’s Point,” he recalls. “Tyler, I believe, had conceived of Miller’s Point maybe a little bit before I started writing Eephus, though I know we were kind of discussing the ideas at a similar time. I wrote Eephus largely during the pandemic, over Zoom, with my two co-writers, Mike Bassa and Nate Fisher. And then eventually when we finally got to work together in a room, we felt like things moved a bit quicker.”

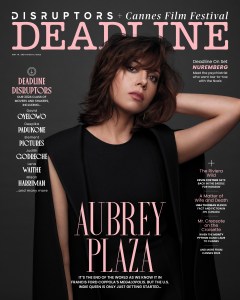

Read the digital edition of Deadline’s Disruptors/Cannes magazine here.

Most of Lund’s career has been as a cinematographer and an editor. “I’d made short films, but I’d never written many screenplays,” he says. “I’m very attracted to location and light — that’s sort of the engine for my creative process — I had stumbled upon an idea where that was sort of the emphasis. Eephus is almost a landscape film, in that respect. I play baseball, and I play in a Sunday League, like the one depicted in the film. I was looking for material that would be personal to me but that also scratched this itch of making a film that would track the process of day turning to night over the course of one afternoon in New England and in fall, which is to me the most beautiful time for baseball.”

The directors were taken aback when both films made it into Cannes. “Honestly,” says Lund, “when one of them got in, we thought, ‘OK, maybe they won’t program both.’ I mean, we don’t want to look like we’re trying to corner the market! But it happened, and we’re thrilled and a little surprised, for sure. But I think it’s a testament to the Fortnight that they’re keeping their eye on these kind of homegrown, handmade, independent films from America. Films that have a kind of different tone and vision.”