Last month, Columbia University Press published Transfigured New York by Brooke Wentz. As an undergrad, Wentz hosted a radio show interviewing experimental musicians and avante-garde artists of the 80s and 90s. The book features never-before-heard conversations with genre-bending musicians that capture the candid and creative energy of downtown New York. In this excerpt, Wentz talks to Philip Glass, notorious composer and pianist, about carving a path in the industry.

———

In the 1980s, no other contemporary composer created more buzz among audiences and in the press than Philip Glass. His repetitive, minimalist style made classical music hip to younger audiences and mesmerized stalwart listeners. His music took its cues from the sustained tones of La Monte Young and Terry Riley’s A Rainbow in Curved Air (1969) and echoed New York colleague Steve Reich’s famed tape loop pieces. But Glass’s subtle, shift-shaping chord progressions were entirely his own.

Glass grew up in Baltimore, where he poured over his father’s record collection as if it were a canonical text. His formal schooling came at the Juilliard School, and he studied in Paris with Nadia Boulanger and Darius Milhaud. Around that time, Glass visited India and met Ravi Shankar and the Dalai Lama, whose expertise broadened his philosophical and sonic palette.

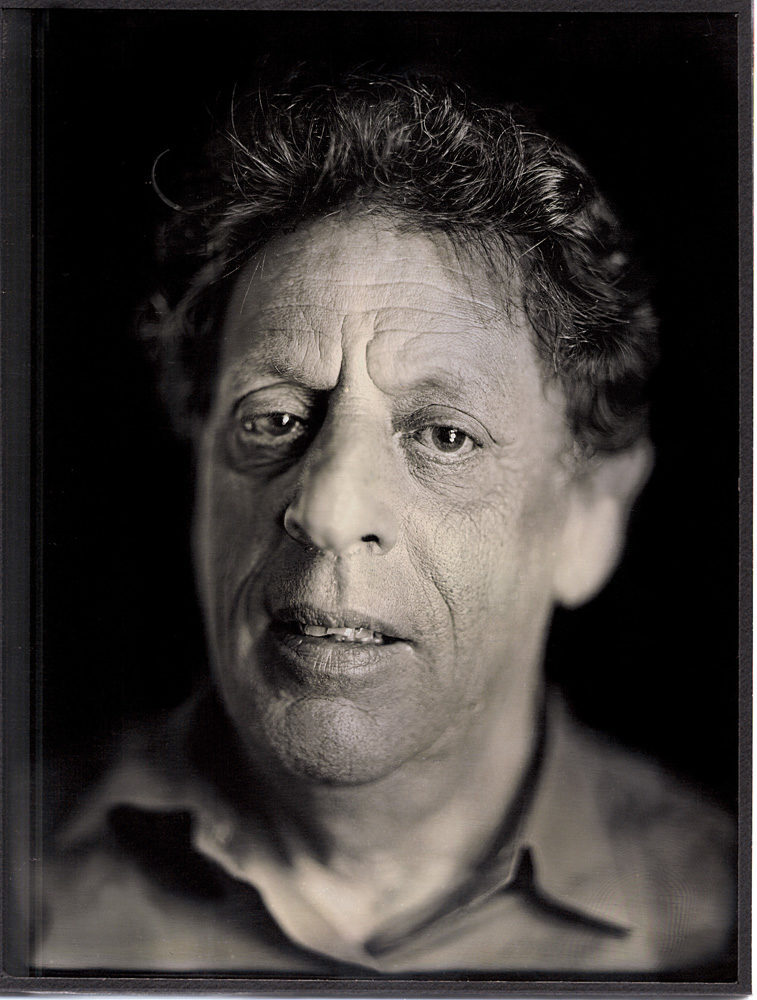

After returning to New York, he began performing small ensemble works in art galleries and for various avant-garde theater productions, including one he cofounded called Mabou Mines in Nova Scotia. Glass was attracted to the trance-like qualities found in Indonesian gamelan music and the soothing sitar of Indian music. His composing style began to bring in voices and electric keyboards. His 1971 composition Music in Twelve Parts was a pivotal four-hour piece that culminated in soprano voice under a twelve-tone theme and launched his definitive composition style for years to come. An upcoming performance of that composition at Town Hall was the impetus for what would be my first artist interview at WKCR. Even for a nineteen-year-old novice, Glass was an easy composer to chat with, with his quick wit, fast Martin Scorsese-like speech, tousled hair, and sad-eyed charm.

———

BROOKE WENTZ: How would you describe your music?

PHILIP GLASS: That’s always a problem. The ways that composers define themselves are broken down now, and that’s a really good thing. It used to be called avant-garde music. Nobody calls it that anymore. Then we called it new music, but that could mean anything. So I think of it as concert music as opposed to, say, popular music. I was trained as a concert musician at Juilliard. I studied with Nadia Boulanger. I had a lot of academic training, so I came out of a world of notated, written-down music. But in a certain way, my music is what you would call abstract music in the sense that it’s music about music. Now, there are certain things about my music that have generated a lot of interest and a large audience: It’s high-energy, and there’s a strong rhythmic profile. So it’s very accessible to people who come out of listening to rock music. We play in both concert halls and in clubs, but I don’t think anyone mistakes us for a rock act. So I think of it as concert music that is very parallel to the popular music of our time.

WENTZ: You have a series of performances coming up at Town Hall here in New York. One of them is a five–hour concert of the experimental opera Einstein on the Beach, which you conceived with director Robert Wilson in 1976. It’s a landmark work. Why not put on the whole opera, with singers and actors?

GLASS: It’s just not practical to put the whole thing together again. That’s a little frustrating, but it’s also frustrating not to be able to hear the music at all, either. So I’m doing an unstaged concert version of Einstein. All the music is there, and I think the theatrical content of the music is still there. The full trilogy did about thirty performances in 1976: Twenty–eight were in Europe and two were at the Metropolitan Opera House in New York. At the time, it was considered too renegade or maverick to find much of an audience. Now I’m talking with some European opera houses that are seriously thinking about producing Einstein again. That way, we would not be financially responsible for the production, which was the real killer with that piece. The thing about Einstein was that it really tied me and the ensemble up for a couple of years—playing it, rehearsing it, staging it, performing it, and then recovering from it. Basically, operas should only be put on by opera houses; they’re just too expensive. It’s like making a movie or something.

WENTZ: Is your work generally more popular in Europe?

GLASS: Every major theater piece I’ve done has opened in Europe and then come to America for only one or two performances. Now with Satyagraha, my latest opera, which is partly based on the early life of Mahatma Gandhi, that opened in Holland and it will be here at the Art Park this summer and next year at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. There has been more interest in that opera because I wrote it for an orchestra and a chorus. Einstein, in the context of the world of opera, was considered a very weird piece. [The opera does not have a plot, and it was written for an ensemble.] In the context of the music world that I live in, it was not considered that weird of a piece. It was just another step in the work that I was doing.

WENTZ: What can people expect from this new one compared to Einstein?

GLASS: I think they better give up any expectations. It doesn’t sound like the son of Einstein. The music of Satyagraha really is, I would say, unrecognizable, except I don’t think anyone could hear it without knowing that I wrote it. And the language of the opera is a language that I chose for its sound value: Sanskrit, which is a beautiful vocal language. Most of the Indian music you hear, when it’s sung, you’re hearing Sanskrit. When I was looking for a text for the opera, I picked up the Bhagavad Gita, which is a Hindu scripture that Gandhi based a lot of his thinking on. And I decided to use that text—which is written in Sanskrit—as a commentary on the action that we see on stage so that the singers are actually singing in a language that we don’t understand. For me, when I hear opera, I find that the literal content of the language is always a problem. Even when operas are in English, I find I understand maybe 40 percent of what they’re saying, and I can never hear the music because I’m trying desperately to hear the other 60 percent that I can’t understand, so I get torn between literary comprehension and musical comprehension. It’s not a very pleasant experience. So in my own operas, I just separate the content of the language into the sound and the meaning. The sound is what we hear. The meaning is often, like, in a book that came with the opera, just like in a regular libretto that you get when you go to an opera house, you quickly read the synopsis before the lights go down for the first act.

WENTZ: You recently produced an album by the New York post-punk band Polyrock. How does that fit into the scheme of what you’ve been doing?

GLASS: I was interested in doing it because I had never done a pop record before. I’ve had a lot of friends in pop music, and I’ve always liked pop music. I’m more inclined to go out and hear a new wave band like Polyrock or an old new wave band like Talking Heads than go to Carnegie Hall and hear the League of International Composers or whatever the heck they are. I don’t listen to that very much. I got the idea of producing a pop record from Brian Eno. We were talking, and he told me how he really liked producing records, and he thought it might be fun for me to do it. I didn’t think about it too much until RCA came to me and asked if I was interested in producing a rock band. I said, “Well, if I like the music, I might: We ultimately decided on the New York band Polyrock. I like them a lot. They play new wave, they’re young guys, they have a lot of energy. It turned out that they knew my music and had been to hear my concerts—which isn’t surprising. We’re all in New York, and a lot of young people come and hear my music. The only problem I had was that it took a really long time to make that record. It was a good month of work, which for me is a lot of time. I enjoyed doing it, but I have a lot of things I want to do on my own. So I’m not really looking to produce more rock records.

WENTZ: Eno’s Ambient 1 album shares some traits with the soundtrack you did for the documentary North Star about the sculptor Mark di Suvero. For the film, you composed short pieces that include repetitive melodies. I was wondering if that album got more airplay than your other work.

GLASS: I wrote short pieces to go with sections of the film that were montages of di Suvero’s sculpture, so the names of the pieces are named after the sculpture. I looked at pictures of the sculpture, and I wrote music in the way that you would write music for a dancer. But instead of looking at a dance or thinking about movement, I thought about the sculpture. So they were like musical portraits. They happen to be short pieces because that’s how the movie went. Virgin Records was very keen to do that soundtrack—I’m sure they were thinking that these were shorter pieces and therefore easier to put on the radio and easier to sell. Whereas more difficult pieces of mine, like Music in Twelve Parts—which is nearly three hours long—have been much harder to get recorded. The North Star record, which was done in 1975, sold more copies than any other record of mine until the Einstein record came out in 1978. And the pieces on that soundtrack were really just little sketches. Not that they weren’t important, but it’s not the same thing as a major work. I think it’s good to find the kind of audience that will maybe listen to North Star, and then maybe later on they will listen to Einstein or Music in Twelve Parts or some of the other things that are heavier and longer and more complex. It’s a good opener for a lot of people.

WENTZ: Will you do more music for film or other multimedia?

GLASS: I’m involved in several things right now. I’m doing the music for a beautifully shot documentary called Koyaanisqatsi, about the decay of cities and the contradictions of technology in the modern world. Kind of heavy socio-political stuff, which I vaguely understand, but I liked very much what they were doing. There are no words in that film at all. It’s just images and music. I’m also working on a third opera now, and I have a kind of chamber opera that I did last year that will be done in New York sometime in the spring. It’s called The Panther. It’s a piece I wrote for six voices, violin, and viola. It’s like a chamber opera for voices and a few instruments. So that’s kind of like a small opera.

WENTZ: How would you describe the direction of music in general right now?

GLASS: It’s very hard for me to say because I’m less of a listener than other people at this point. I remember talking to the composer Moondog years ago. He lived at my house for about a year in 1970, and I got to know him pretty well. He was telling me about these pieces he did as a young man that would last all night and that changed rhythms and that went on and on and on. I said, “Moondog, that sounds great, what happened to those pieces?” He said, “Well, there I was leading the pack, and I turned around and no one was following!” So the thing is, I know what direction I’m going in. I’m not sure whether other people are with me or not.