For one more night, the papaya bar still beckons at the Conga Room in downtown L.A.

The yellow sculptural design from Cuban American artist Jorge Pardo — meant to resemble the tropical fruit split open — has served cocktails to Latin music lovers since this incarnation of the Conga Room opened at L.A. Live in 2008, a decade after the club debuted in Miracle Mile. The murals of angelic luchadors, from artist Sergio Arau, are still up for now, as are the ceiling panels meant to resemble a cascade of flowers.

“This thing is not evergreen,” said co-founder Brad Gluckstein, looking over a wall of portraits and concert shots taken on the Conga Room’s stage. “But it’s allowing a really exhilarating transition, as opposed to just longing for what was. Twenty-five years is a long run.”

The Conga Room’s papaya bar.

(Wally Skalij / Los Angeles)

The Conga Room will go dark forever on Wednesday with what’s expected to be a rowdy, teary send-off show. The closure marks the end of a chapter in local Latin music, one in which the Conga Room cultivated multiple generations of stars and brought titans of music history through its doors, from Celia Cruz to Bad Bunny, Los Van Van to J Balvin.

The music that the Conga Room has championed since the ‘90s has never been more popular globally. Amid the success of Latin music on stadium tours, festival stages and streaming platforms, the venue’s founders are making peace with what that has meant for their nightlife niche. They can reflect on the impact that the Conga Room had — and why it’s time to let it rest.

“All that’s happening right now in front of us is probably, to a certain degree, because of us,” Gluckstein said. “I don’t think LeBron’s scoring record will ever be broken, and I have a hard time believing that in Los Angeles, you’ll see a run with the same success that we had.”

Legendary singer Celia Cruz performs at the Conga Room in 1998.

(Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

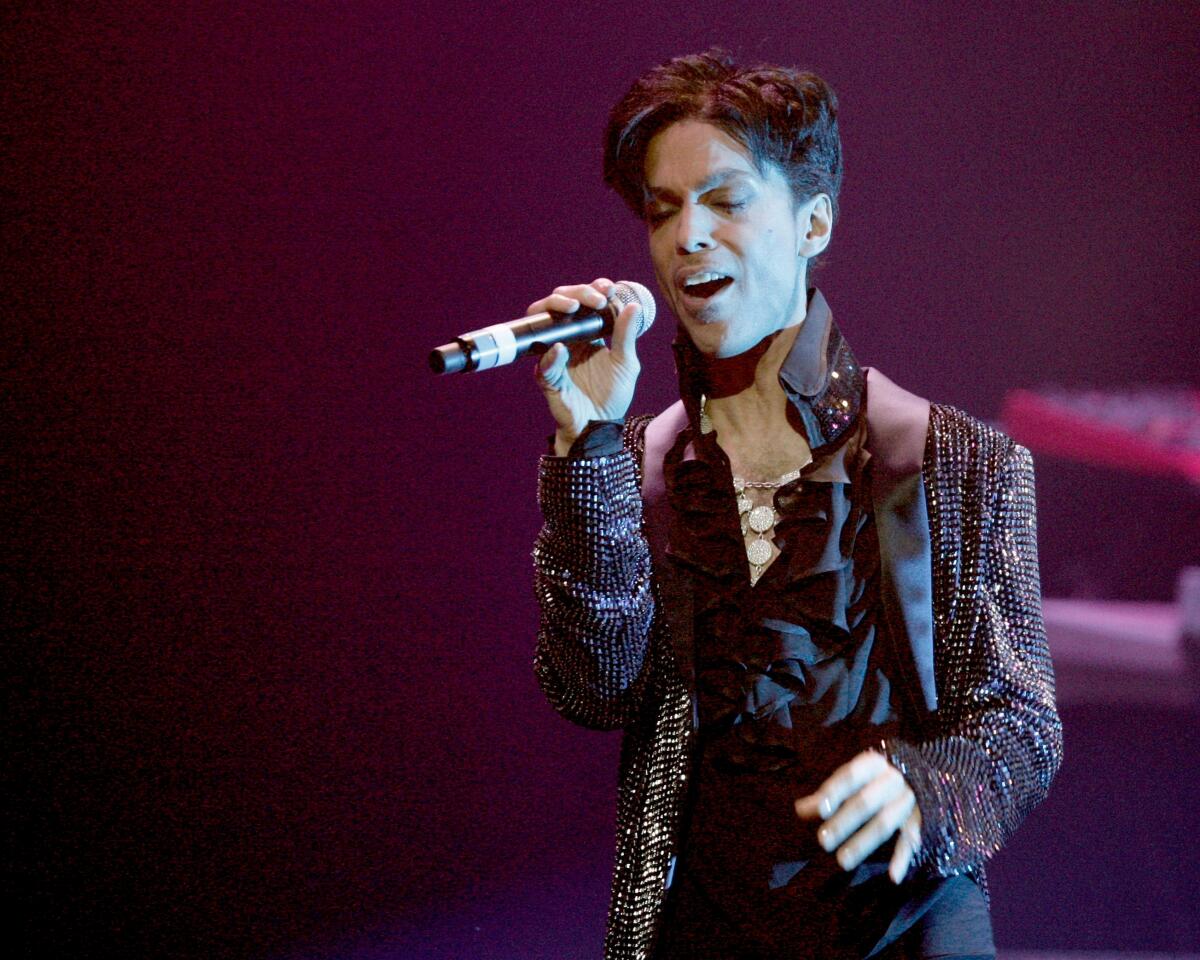

Gluckstein and his co-founder, “NYPD Blue” and “L.A. Law” actor Jimmy Smits, are sifting through decades of memories. In the green room, Gluckstein has a photo album in which his much-younger self poses with Jennifer Lopez and Willie Colón, the Boricua salsa music titan. Smits laughed as he recalled one overpacked night where he got roped into manning security detail at the height of his TV fame. Both reverently recalled Prince cornering them backstage before a gig to advocate for artists to get paid when DJs spun their records.

“It’s been like losing a family member,” Smits said. “I came here from New York and was searching out any kind of tropical music. On any given night, you could come and see people wearing cowboy hats, or people dancing their asses off for reggaeton nights. Sheila E was involved from the beginning, and one of my fondest memories was Prince taking the stage here. The club was able to give voice to a kind of panorama of what Latino music can be.”

Prince performing at the Conga Room in 2009.

(Kevin Winter / Getty Images)

When the Conga Room first opened in 1998, Latin music was in one of its waves of commercial success among wider audiences. Celebrities such as comedian Paul Rodriguez, singer Tito Nieves and record label owner Ralph Mercado signed on as investors to open the 400-capacity room, within walking distance of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

Ricky Martin and Lopez (another co-investor) were ascendant pop stars, and rock en español acts such as Maná were winning acclaim. The Selena biopic brought fresh attention to the late Tejana star’s music, and in 1999, Wim Wenders’ documentary on the Cuban group Buena Vista Social Club renewed global interest in the Latin music of the Caribbean.

On opening night in 1998, when Cuban singer Celia Cruz headlined, The Times noted that “a very interesting paradox … lies at the heart of the venue: A lot of money has been spent to re-create the smoky atmosphere of the kind of Cuban clubs that were originally geared toward the working class. Of course, bring somebody like Cruz on stage and the whole evening turns into a family affair.”

“We were doing things that nobody had ever done on the West Coast,” Gluckstein said. “We had a steady diet of Cuban music, Los Van Van and Pablo Milanés. We had gigantic salseros who would normally play to 10,000 people in Colombia or Venezuela. We were privileged to be able to feature them, and they were excited because of the sound quality and the way we treated artists.”

During his run as mayor, James Hahn shakes hands with supporters at a Conga Room party.

(Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times)

The club became a favorite spot for politicians to mingle, and it hosted the Democratic National Convention kickoff party in 2000 with Bill Clinton and Al Gore attending. It hosted the Latin Grammys after the 9/11 attacks canceled plans at the Forum.

When the club migrated to the freshly constructed L.A. Live after a two-year hiatus, what had been an intimate spot for music discovery turned into a gleaming showcase for Latin music at the heart of downtown’s sports and music megaplex. “Our first venue was a hole in the wall,” said Gluckstein, fondly. “Despite the trappings of L.A. Live, how clean and industrial this complex is, we dreamt big.”

Oscar Hernandez, leader of the Spanish Harlem Orchestra, came on as music director. The venue also diversified from its salsa roots, giving the actor Jamie Foxx’s R&B band a long-standing residency, and booking early gigs from Ed Sheeran and Avicii. As the wave of reggaeton and música urbana began to crest, the Conga Room booked some of the first L.A. shows for Maluma, J Balvin and Bad Bunny.

“Bad Bunny canceled his tour’s club dates the day after our venue,” Gluckstein said. “We were really advanced. You never saw him in a club again.”

“The music changes, that’s the beauty,” Smits said. “Latinos like how the influence of the older styles of music gets mixed in. We’ve tried to preserve those tropical nights, but to give exposure to different genres of Latin music. When it started with reggaeton and how hip-hop influenced the whole way this music is perceived, we adapted.”

Part of the Conga Room’s space at L.A. Live.

(Wally Skalij / Los Angeles)

Yet the club’s prospects dimmed, like it did for so many others, when the pandemic hit.

“We were killing it before the pandemic. Our club nights were off the charts, and we were booking a lot of events,” Gluckstein said.

But they returned to find younger fans’ nightlife habits had changed, right as acts like Bad Bunny were headlining Coachella and Mexican music acts like Peso Pluma and Fuerza Regida became megastars on TikTok.

“Artists are having a hard time making a living other than what they’re getting paid to do concerts. So that ratchets up the price to make tours more viable,” Gluckstein said. “I think it’s become talent-based and not club-centric. Kids aren’t going to big dance halls as much. If they do see a Latin concert, they’re going to the Forum.”

Gluckstein said that after 25 years running nightclubs, he wanted to concentrate more on his youth charity, Conga Kids, which brings Latin music and dance classes to 50,000 local youth. But first he will memorialize one of the foundational venues in modern Latin music.

At the Wednesday party, Gov. Gavin Newsom will appear in a sendoff video, and a who’s-who of politicians including Sen. Alex Padilla, former Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa and state education Superintendent Tony Thurmond will speak. Gilberto Santa Rosa, fondly known as “El Caballero de la Salsa,” will lead a 16-piece orchestra, and the night will wrap with a jam session led by Jerry Rivera (“El Bebé de la Salsa”) and Santana’s singer, Andy Vargas.

Latin music is at its most exciting zenith in U.S. since the late ‘90s, when the Conga Room debuted. Gluckstein and Smits said they’ll part ways with the venue with no regrets. But who will take the papaya bar home?

Gluckstein laughed and said maybe he would. ”Only if we have enough ground in our backyard and it can deal with rain,” he said. “It’s a fickle city.”

“We dreamt big,” said Brad Gluckstein, left, with Paul Rodriguez and Jimmy Smits.

(Wally Skalij / Los Angeles)