A quarter of a century ago, Bob Dylan found vital new life in an album about death’s inexorable approach.

“I’m walking through streets that are dead,” the rock ’n’ roll legend sang — wheezed, really — right at the top of “Time Out of Mind,” which came out in the fall of 1997 to end the longest break he’d ever taken from releasing original material. Dylan, then 56, hadn’t been silent in the years since 1990’s coolly received “Under the Red Sky”: He’d put out two collections of folk and blues standards and had reestablished himself as a can’t-miss live act on what came to be known as the Never Ending Tour; he’d even followed Paul McCartney and Neil Young (and Tony Bennett) onto MTV’s hit “Unplugged.”

Yet recording new tunes of his own, he told interviewers at the time, no longer held much appeal, which led many to wonder if the songwriter who changed rock — who convinced the world, for better or for worse, to take rock seriously — had finally run out of things to say.

Then came “Time Out of Mind.”

Produced by Daniel Lanois, who’d worked with Dylan on 1989’s “Oh Mercy” and with U2 and Peter Gabriel, the 11-track LP set stark thoughts of heartache and mortality against bleary blues-based arrangements performed live in the studio by a murderers’ row of players that included guitarists Bucky Baxter and Cindy Cashdollar, keyboardists Jim Dickinson and Augie Meyers and drummers Jim Keltner and Brian Blade. The sound was lush, fervent and slightly spooky, with Dylan’s voice in a state of glorious decay as he dispensed bleak aphorisms like “It’s not dark yet but it’s getting there”; that he was hospitalized with a potentially fatal heart infection shortly before the album’s release only bolstered its apocalyptic vibe.

“The sonics and the atmosphere that Bob and Daniel and the band put together are so haunting and so evocative of what he’s singing about,” says Bonnie Raitt, a lifelong Dylan fan who covered two of the album’s songs — the strutting “Million Miles” and the tender “Standing in the Doorway” — on her 2012 LP “Slipstream.” “It laid bare the whole spectrum of color in his voice — riveting and vulnerable and gritty. I just think it’s one of his best records ever.”

Raitt isn’t the only one. Dylan’s first million-seller since “Slow Train Coming” in 1979, “Time Out of Mind” finished atop the Village Voice’s annual Pazz & Jop critics poll and was named album of the year at the 40th Grammy Awards — Dylan’s first and only win in that prestigious category. Looking back, it’s clear the record also marked the beginning of a third act in Dylan’s career that’s still playing out today, as he showed with 2020’s pulpy “Rough and Rowdy Ways” and its accompanying world tour, which stopped last year, weeks after his 81st birthday, at Hollywood’s Pantages Theatre for a spellbinding few nights.

Now a deluxe box set seeks to chart Dylan’s path to rejuvenation. Due Friday as the latest installment in his ongoing Bootleg Series of archival material, “Fragments — Time Out of Mind Sessions (1996-1997)” offers five discs of outtakes, alternate versions and live recordings of songs from “Time Out of Mind” as well as a remixed edition of the original album, whose cuts include the 16-minute “Highlands” and “Make You Feel My Love,” which has been covered by Adele, Billy Joel, Garth Brooks, Michael Bublé and Pink, among countless others.

In a typically Dylanesque move, the crisp new mix by Bootleg Series veteran Michael Brauer clears away some of Lanois’ signature studio murk — precisely the thing, that is, that helped listeners hear Dylan in a fresh way back in the late ’90s.

“It’s more of a singer-songwriter approach,” Brauer says of his take on “Time Out of Mind,” which features smoother, less-processed lead vocals; still, Brauer adds, he was determined to “maintain the integrity and the essence of an iconic record.” (Dylan himself has expressed ambivalence about the album, telling Rolling Stone in 2001 that Lanois’ “swampy voodoo thing” resulted in a “sameness to the rhythms.”)

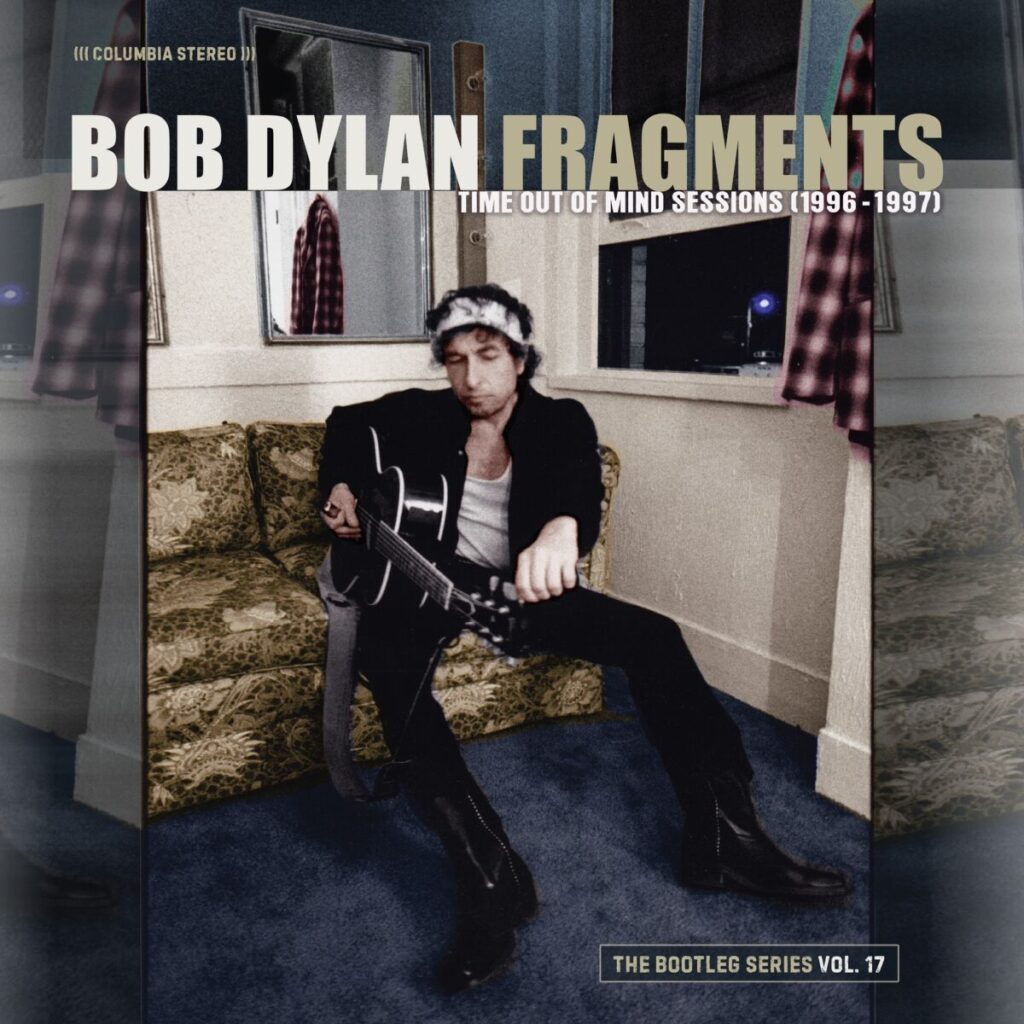

The cover of Bob Dylan’s “Fragments — Time Out of Mind Sessions (1996-1997).”

(Columbia Records)

Yet the box set’s fascinating outtakes reveal Dylan’s search for a spark as he tries out different grooves, different licks, different chord progressions in songs such as “Love Sick,” “Not Dark Yet,” “Cold Irons Bound” and “Tryin’ to Get to Heaven.” The funky “Can’t Wait,” about a man desperate to “recover the sweet love that we knew,” is alone presented seven times on “Fragments,” each with its own distinct flavor — one a little trippier, one a little swaggier, one a little more menacing.

“We didn’t know what this album was going to be,” Lanois tells The Times, recalling his explorations with Dylan on “Time Out of Mind.” “But we had courage, and we believed in the people in the room.”

As historian Douglas Brinkley writes in “Fragments’” liner notes, Dylan likely started composing “Time Out of Mind” in the wake of the 1995 death of his close pal Jerry Garcia of the Grateful Dead (whose “Friend of the Devil” Dylan performed affectionately at the Pantages). The next year, having written most of the tunes over the winter at his farm in Minnesota, he met with Lanois to discuss a possible reunion after “Oh Mercy,” the recording of which Dylan recounts in detail in his 2004 memoir “Chronicles: Volume One.”

Given the friction of those sessions, was Lanois surprised to get the call? Not really, he says. “‘Oh Mercy’ was a soulful record — flawless in a certain way. But I gotta be honest with you: After that, Bob did a couple things that just didn’t have it.” The producer says he doesn’t want to single out any of Dylan’s subsequent collaborators by name. “Let’s say he was working with Don Quixote. I felt like calling Don Quixote and saying, ‘What did you do? You responded to a party invitation, but you couldn’t admit you never really got there.’” (“Under the Red Sky” was produced by Don Was.) “You can say anything about me,” Lanois continues, “but I’m not a brown-noser. I won’t tell people what I think they want to hear. I’ll tell them the truth. And so I think Bob felt he could trust that part of me, and that’s why we went back in.”

Dylan’s first directive to Lanois was to study his favorite old blues and early rock records by the likes of Charley Patton, Little Walter and Little Willie John — “records that are dripping in sweat and that have a sense of unfolding and discovery,” as Lanois puts it.

Demo sessions began at Lanois’ makeshift studio in a converted movie theater in Oxnard, not far from Dylan’s home on Malibu’s Point Dume. “The place was dripping in vibes,” Lanois says of the theater, where he later cut Willie Nelson’s 1998 album “Teatro.” “It had a vending machine with wax lips in it, and we discovered hundreds of old Mexican movie posters in the projector room that we hung up in the popcorn area. Bob loves old posters.”

Blade, who’d played on Emmylou Harris’ Lanois-produced “Wrecking Ball” and who’s also collaborated with Joni Mitchell, remembers driving up to Oxnard one day and jamming with Dylan and Lanois on the Scottish folk song “The Water Is Wide.”

“Bob was really warm and funny and open to talk,” Blade says. “He was wondering if I’d played with Little Richard, which I found interesting and hilarious. I was like, ‘No, but I’d love to.’”

Dylan soon moved the sessions to Criteria Studios in Miami, where Lanois convened the group of more than a dozen players, including old hands like bassist Tony Garnier and folks new to the Dylan fold like Dickinson, the seasoned Memphis producer and instrumentalist who died in 2009. As he had in Oxnard, Dylan peppered the musicians with questions about the pioneers with whom they may (or may not) have played. Says Dickinson’s son Luther, a musician himself with the North Mississippi Allstars and the Black Crowes: “First day at Criteria, my dad’s in the parking lot lighting up a joint, and Dylan walks straight up to him and starts asking him about Sleepy John Estes.”

According to Blade, the band was arranged in the studio in a “massive circle,” with everyone able to see everyone else, though “there was never any discussion or allocation of duties — no breakdown of what was gonna happen,” the drummer says.

Lanois advised the players to envision Dylan as a train running down a track and themselves as the scenery rolling by. “We see a cactus, then a dog, then a hobo, then a disintegrated monument, then a rainstorm,” he says. “You’re the cactus, and a cactus doesn’t play something it played the night before.” Indeed, Dylan would tweak not just the melody or the tempo or the lyrics between two takes of a given song but also change the key, as you can hear in one of those renditions of “Can’t Wait,” which starts with a bit of studio chatter: “How ’bout B-flat?” Dylan asks.

“I don’t think anybody reworks things as radically as Bob does,” says Raitt. “He’s alone in that.”

Bob Dylan performing in 2012.

(Chris Pizzello / Associated Press)

He also sprang new material on the room. Lanois says Dylan pulled “Make You Feel My Love” out of nowhere, “which surprised the hell out of me. I knew all the songs because I’d worked up the band before Bob even got to Miami, and I’d never heard that.” The producer wasn’t sure what to think of the tune, a more conventional and sentimental number than the others on “Time Out of Mind.”

“It’s one of the most used-up chord sequences in the history of music,” Lanois says of “Make You Feel’s” descending progression. “And maybe a little bit corny — like something out of ‘Mary Poppins.’ But sometimes you gotta just get out of the way, so that’s what I did.”

Other times he didn’t. The tensions involved in the making of “Oh Mercy” flared up again at Criteria Studios, with Lanois famously smashing a guitar at one point in frustration. And the singer wasn’t to be outdone. “Dad told me that Dylan picked up a dobro and was swinging it around in a circle over his head,” Luther Dickinson says with a laugh. “He said he could feel the wind brushing past his face.”

Yet that volatile chemistry infused the music with feeling. Blade hears the album as a “balance struck with great perfection. It’s ecstatic and it’s contemplative. There’s urgency and there’s stillness,” he says. “The known and the unknown, it all exists in ‘Time Out of Mind.’”

The LP’s triumph at the Grammys, where it beat Radiohead’s “OK Computer” for album of the year — and where Dylan’s performance of “Love Sick” was memorably interrupted by a shirtless dancer with “Soy Bomb” scrawled across his chest — gave Lanois a sense of reassurance about the music industry. “It took balls to celebrate such a dirty record in a time of such cleanliness,” he says.

Though Dylan hasn’t used a producer since “Time Out of Mind,” instead running his sessions himself under the pseudonym Jack Frost, his records have stayed in touch with the essential earthiness he got in the studio with Lanois. Asked if the two still talk, Lanois said Dylan came over to his place after he’d finished one of the standards collections he released in the mid-2010s.

“He wanted me to hear it, so I made some coffee and before he played a song he talked for two hours,” Lanois says, adding that Dylan told him he felt he had a responsibility to the old music “because it came from innocent times. He said, ‘Some of these songs were written by soldiers who were in World War II, and they were just sending a letter of a song to a lover.’

“That’s rare these days,” Lanois says, “because we’ve all lived so much and we all know everything” — not least the doom-attuned narrator of “Time Out of Mind.” “But making that record we found innocence somehow.”