After two seasons of an extended Cold War, For All Mankind moved into the technology boom of the ’90s. If the real ’90s were driven by a techno-optimism, For All Mankind explores an idea of what a utopian America driven by technology would actually look like. In this alternate space-focused timeline, the go-go ’90s are filled with electric cars, videophones, and moon-mining. Sounds pretty good, right? But over the course of the season, For All Mankind shows how even if the utopianism of the actual ’90s could have been translated into reality, we couldn’t have left our problems behind.

By the third season, For All Mankind’s alternate history has moved leaps and bounds beyond where our ’90s found us. The larger powers have wound down their military snafus in Vietnam and Afghanistan to focus on building military bases on the moon. The Equal Rights Amendment entered the Constitution thanks to the prominence of female astronauts, electric cars are readily available thanks to investments in technology, and the Soviet Union never collapsed.

It placed its own heroes, like Ed Baldwin (Joel Kinnaman), Danielle Poole (Krys Marshall), and Gordo Stevens (Michael Dorman) alongside the Aldrins and the Rides. Real-life figures got moved around like chess pieces, with Ted Kennedy becoming president after Nixon, and Reagan after that. They talk with characters through a combination of voice actors and deepfakes.

Real-world characters exist in season 3, but they start to take the backseat to the show’s world. The rise of computers and the internet doesn’t factor much into the show, because all of the exciting technology, for decades, has been focused on sustaining life in space. While it’s not a one-to-one analogy, replacing “computers” with “space travel” allows For All Mankind to make fascinating commentary. Instead of exploring Jobs, Gates, Andreessen, and the culture of ’90s Wired, For All Mankind wraps them all up in Dev Ayesa (Edi Gathegi).

Photo: Apple TV Plus

A charismatic billionaire who wants to go to Mars has obvious parallels to Elon Musk, but Ayesa doesn’t resemble the hyper-visible billionaire. He owns only one company, Helios, not four. He rejects titles and a corner office, working directly among his employees. Helios employees practice office democracy, conducting public votes on major company policy. And, most tellingly, Elon Musk doesn’t compete with NASA — SpaceX works extensively with the government.

Ayesa feels more similar to the techno libertarians from the ’70s through the ’90s who saw technology as a means of personal liberation, who historian Fred Turner called the New Communalists. As Turner describes in his book From Counterculture to Cyberculture, they saw “the cybernetic notion of the globe as a single, interlinked pattern of information” as “deeply comforting.” The “invisible play of information” would bring about “global harmony,” a break from the harsh lines drawn in the Cold War.

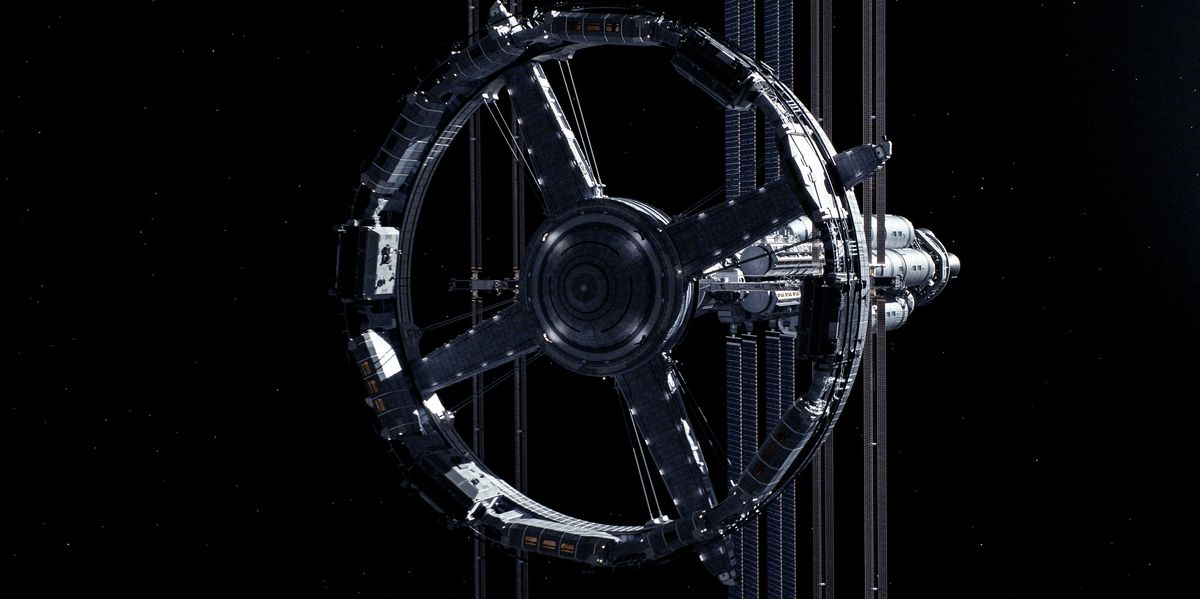

In For All Mankind, Ayesa looks on in horror as the moon becomes a battleground for world powers and is then split in half, with one piece for the U.S. and the other for the USSR. He wanted to beat both of them to Mars, creating a free enterprise zone which would essentially be invisible to most of the human population on Earth, but would challenge both ideologies. The key, above all else, is being first. And, considering how advanced space tech is at this point, he didn’t even need to build everything himself. Taking advantage of a terrifying space hotel disaster in season 3’s first episode, he buys the technology Helios needs to take on NASA and the USSR in a race to Mars.

Ayesa continues his buying spree, poaching NASA employees disgruntled with the low pay and stuffy sense of order. It’s hard to blame them, considering that while NASA’s economic position in For All Mankind has radically improved, they haven’t seen a salary increase in years. When employees at Helios debate the company’s issues, like who should lead the company’s mission to the Red Planet, they start to feel heard. A communal structure and capitalist enterprise make for a romantic vision.

Photo: Apple TV Plus

Photo: Apple TV Plus

Photo: Apple TV Plus

Photo: Apple TV Plus

For All Mankind was co-created by Star Trek alum Ronald D. Moore, and the show references the franchise from time to time. Long associated with utopianism, it is derided as out of date in the ’90s of season 3, where astronauts prefer the hellish fantasies of Aliens and melodramas about their own heroes. As both Helios and a very profitable NASA promise, the utopia is already here.

And yet, as the show continually reminds its characters, there is no end to the number of things that can go wrong in space. There’s no oxygen or gravity, no atmosphere to protect from radiation, and a massive distance between points of interest with no means of fast-traveling. There’s the isolation from most of humanity, as well as the confinement in close quarters for years at a time, which, on a trip to Mars, would lead to what NASA (in our universe) deems “inevitable” behavioral issues. For All Mankind fans have already seen these issues play out on Jamestown base alongside episodes of The Bob Newhart Show.

The phrase “space is hard” has become such a standard saying within the industry that the U.S. Space Force has used it in commercials. But it’s more than hard, it’s horrifying, and For All Mankind doesn’t shy away. Characters die brutal deaths in For All Mankind, from being burned alive in a spacesuit to bleeding out of their eyeballs after being exposed to a harsh lunar landscape.

These deaths are mourned and memorialized, but they don’t stop anyone from heading up into the skies. Neither Ayesa’s space-libertarianism or NASA’s trust in military-style structures stop disasters in the most unforgiving environment imaginable, a place where the tiniest piece of debris can destroy an entire ecosystem. The only option, For All Mankind argues, is to eventually, somehow, in all sincerity, even if it’s just a little bit at first, work together.

Photo: Apple TV Plus

Photo: Apple TV Plus

While the Mars mission is successful in the sense that boots are on the ground, it starts to fall apart afterward. Much like in the actual ’90s, an underground movement of anti-government extremism is downplayed in For All Mankind until it’s tragically too late. Like Timothy McVeigh, the perpetrators of the terror attack at the season’s end are ex-military. Transferring the real world over to For All Mankind’s space focus, the events of Jamestown become as radicalizing as the Waco siege.

The world is upended in For All Mankind’s final episodes: The President is openly gay, neither the Soviets or Americans were first to Mars, it turns out, and Johnson Space Center lies in ruins. Space is suddenly a financial and political liability, with the dreamers like Ayesa and Margo Madison shut out of their own institutions.

The heroics of Gordo and Traci Stevens couldn’t be further in the past. As the twinkling of Radiohead’s “Everything in Its Right Place” introduces the 2000s, characters find their lives completely upended as an age of space heroism moves into a time of deep uncertainty. Thom Yorke’s haunting vocals, born out of his mental breakdown following the success of OK Computer, fit perfectly with the quick shot of Margo waking up to her new life in the 2003 Soviet Union (not since The Americans has a show been this good with needle drops).

But still, amidst all the chaos, the show feels like Moore’s version of the dreadful Star Trek: Enterprise, examining the earliest beginnings of a Star Trek–like society. The Earth may have changed, but space is still above, calling out for exploration.

Despite what any billionaires tries to sell you, the road to a life among the stars wouldn’t be easy. Lives would be ruined. A sense of adventure would fade away. Humanity would be dragged kicking and screaming into the future, lugging the inequalities, hatreds, and petty squabbles of the Pale Blue Dot alongside the rations on a trip across the solar system. But For All Mankind argues that shit hitting the fan knows no language or ideology. If anyone wants to succeed out there in the Great Beyond at all, there’s just no other option.

For All Mankind season 3 is streaming on Apple TV Plus.