When Amy Sedaris makes appearances around the country, she finds it easy to identify the “Strangers With Candy” fans in the audience.

“They’re ugly,” she says with a cackle. “They’re misfits and outcasts.”

Stephen Colbert tells a similar story.

“If you’re walking on the street and you see somebody wearing a trash bag and talking to themselves with shaved eyebrows, you know that’s probably a ‘Strangers With Candy’ viewer,” says “The Late Show” host. “And you’re often right about it.”

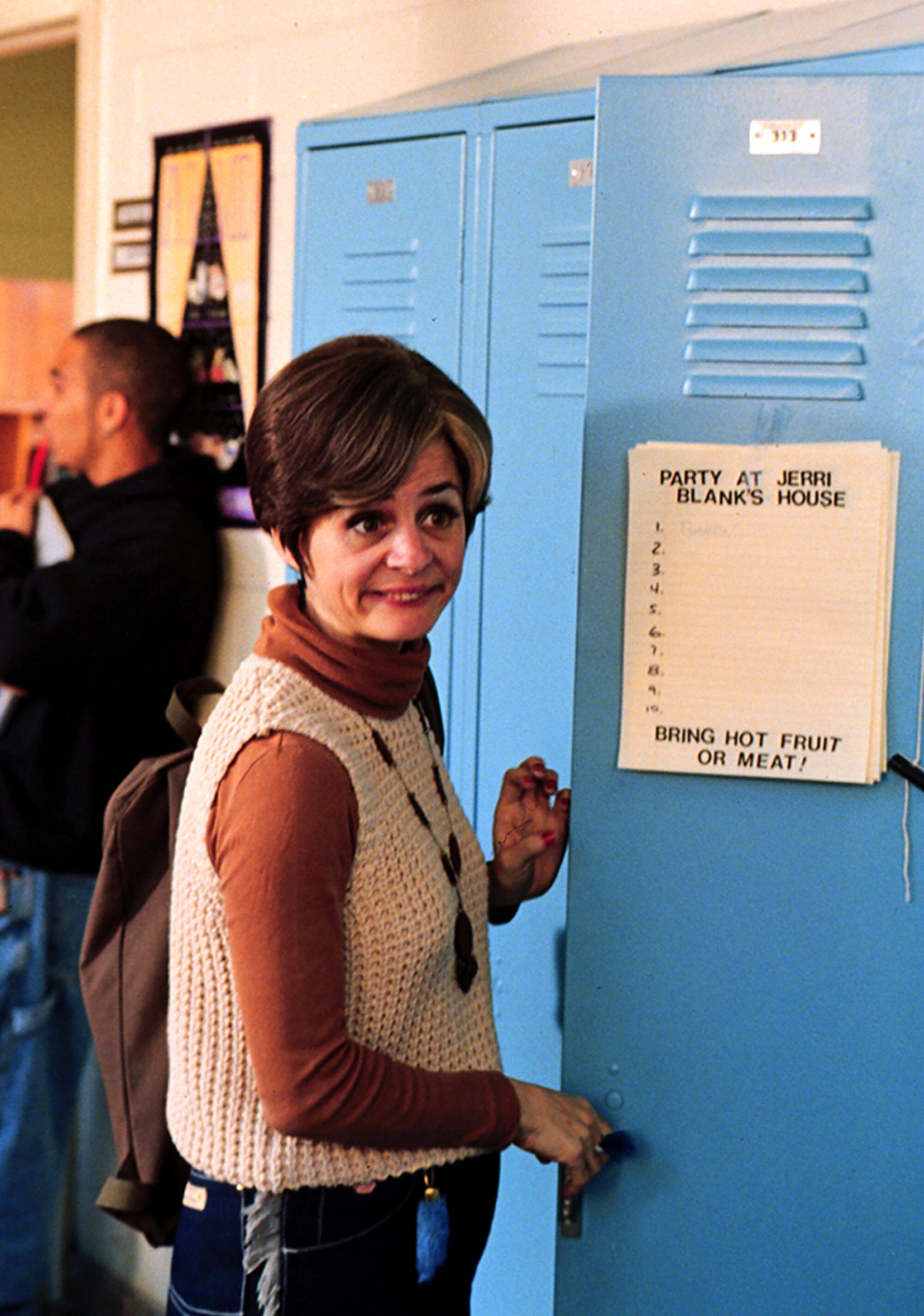

Twenty-five years ago, the show — a warped spoof of the heavy-handed “ABC Afterschool Specials” of the ‘70s and ‘80s — premiered on Comedy Central, and hardly anyone noticed. It starred the rubber-faced Sedaris as Jerri Blank, a 46-year-old high school freshman and semi-reformed drug addict who returns to her hometown after decades on the lam and tries to pick up where she left off as an adolescent. For guidance, she turns to her factually challenged history teacher, Chuck Noblet (Colbert), who is having an illicit affair with insecure art teacher Geoffrey — pronounced “Joffrey” — Jellineck (Paul Dinello). Each episode dealt with an issue of the week — from racism to eating disorders — with Jerri learning almost nothing along the way.

Though it debuted in the time slot after the white-hot hit “South Park,” “Strangers With Candy” never found much of an audience in its original three-season run. Unlike other shows of the era, it did not permanently alter the cultural landscape or ignite a TV revolution. It won no awards and the critics who bothered to write about the show were generally either baffled by its absurdist tone or offended by its outrageous humor.

But over the years, through cable reruns, DVD boxed sets shared with friends and clips that circulate on social media, “Strangers With Candy” grew into a cult favorite. Comedy nerds and oddballs of all stripes embraced the show, especially its singularly off-putting heroine, a woman with a garish overbite, a sordid past and a strangely infectious nasal drawl. “For 32 years I was a teenage runaway,” says Jerri in a direct-to-camera monologue in the show’s first episode, in which she accidentally kills the most popular girl in school with a homemade batch of a drug called “glint.” “My friends were dealers, cons and 18-karat pimps. But now I’m out of jail, picking up my life exactly where I left off: Back in high school, living at home and discovering all sorts of things about my body.”

Although the creators of “Strangers With Candy” — Colbert, Sedaris, Dinello and Mitch Rouse — never set out to influence anyone, the show has inspired younger writer-actor-comedians like John Early, Lena Dunham and Ilana Glazer. And, if you squint, it’s possible to see traces of Jerri in the messy women who now seem to be everywhere on TV. Although it’s unlikely anyone could — or should — remake the show in 2024, its filthy, irreverent spirit lives on.

“A lot of people come up and say that it changed everything, that it changed the rulebook,” says Sedaris, speaking by phone from her home in New York while cooking up a batch of marinara sauce. “I think we broke the rules because we didn’t really know what the rules were.”

The story of “Strangers With Candy” began in Chicago, where Colbert, Dinello and Sedaris were members of the Second City improv troupe and performed comedy in dodgy bars around town. They later moved to New York and wrote and starred in a quirky sketch show called “Exit 57,” which aired for two seasons on Comedy Central. A few years later, Colbert and Dinello were close to clinching a deal with Comedy Central for a show called “Mysteries of the Insane Unknown” — a quasi-parody of “In Search Of” cobbled together from found footage. “Our pitch was that this is going to cost you $1.25 to make,” says Colbert, in a joint phone call with Dinello. “They literally said, ‘Let’s cut you guys a check.’ We were like, ‘Oh, my God,’ because we were only mildly employed back then.”

Then Sedaris called Dinello and asked for their help with a pitch for an update on the “Afterschool Specials” they’d all grown up watching.

“Paul told me the idea. And I said, ‘Paul, goddammit, that’s a better idea,’” recalls Colbert, who worried that Comedy Central might prefer it to the idea they had just sold. This turned out to be the case, and “Mysteries of the Insane Unknown” never came to fruition. But the concept for “Strangers” was dramatically retooled before the show made it to air.

Sedaris originally imagined a straight re-creation using the original scripts. But Dinello had gotten a copy of an educational film called “The Trip Back” from Kim’s Video, the legendary East Village emporium known for its collection of obscure titles. The PSA featured Florrie Fisher, a motivational speaker, lecturing a group of high school students about her struggles with drug addiction using colorful terminology. (“I can’t smoke one stick of pot! I can’t take one snort of horse!” she says.) Fisher happened to bear a resemblance to Sedaris.

“I said, ‘Amy, you should be that character,’” says Dinello, who is now a writer and supervising producer on “The Late Show.” “Then Stephen had the idea that it would be an ‘Afterschool Special,’ but we’d always teach the wrong lesson.” They shot a pilot that was “really bad,” according to Sedaris, and never aired. (In the episode, Jerri is asked to spy on another girl and look for signs of an intellectual disability, though a different term was invoked.)

But with help from programming executive Kent Alterman, they reshaped the series. The cast included Deborah Rush as Sara, Jerri’s cruel stepmother; Roberto Gari as Jerri’s beloved father, Guy (who, in a running gag, always appeared motionless on camera); Maria Thayer as Tammi Littlenut, Jerri’s redheaded classmate and crush; and Greg Hollimon as Onyx Blackman, the formidable principal of Flatpoint High School.

At the time they were developing “Strangers With Candy,” basic cable was still mostly a wasteland filled with reruns and old movies. But a few networks were experimenting with scripted shows that were subversive and formally inventive.

Comedy Central was just about the only place you could go “if you had a weird, less mainstream idea,” Dinello says. “It had a lot of people like us, younger comedians that were looking to do something a little off the wall.”

But there was a catch, Colbert says: “You had to be willing to work for no money and have no one watch your show.”

Although they tried to find other writers on the series, Colbert, Dinello and Sedaris churned out virtually all the scripts themselves, using a free-form method informed by their years in improv.

“We purposefully would never write an outline,” says Colbert. “Because we started off as improvisers, we believed that discovery was better than invention. And if you do an outline, you’re just sort of filling in the slots of the thing you want to invent.” If they thought something was funny, it stayed. Though it tackled “issues,” “Strangers” was never topical or political, and made few references to the real world — as if its characters existed in another dimension.

They imagined all the scripts were written by a middle-aged woman named Jocelyn Hershey Guest, their own version of J.D. Salinger alter ego Buddy Glass, the voice of several of the author’s short stories. “In the world where she’s writing, these are the right moral choices,” Colbert says. “That’s why in our mind, they all have an internal consistency. And also it freed us up from thinking that we were writing this bad stuff. It was all Jocelyn doing it.” (The name was something Amy’s brother, the humorist David Sedaris, came up with in a play.) The process was not especially efficient, but it was, in its way, fruitful. “There’d be nights where we would write all night long, go to set, shoot the thing we just wrote and then go back to the office and keep writing. We were sleeping so little. I think that actually literally did lead to some of the weirdness of the show,” says Colbert, who was juggling “Strangers” with a gig as a correspondent on “The Daily Show” while also developing a show for ABC.

This meant they were always rewriting at the last minute, Sedaris recalls. “Jerri had these really long monologues and then we’d have to cut them down. And sometimes you can see me reading [my lines] off the wall.”

Their creative approach also meant embracing mistakes and moments of serendipity. They couldn’t decide on Jerri’s last name so they just left a blank space where it would go in the script. Someone read it aloud as “Jerri Blank,” and everyone burst into laughter. “Like so many things in the script, the universe would accidentally go, no, you actually wrote the right thing. Don’t try to make it better,” Colbert says.

Sedaris describes Colbert and Dinello as the “woodchoppers” and herself as a “decorator.” “I’m good for ideas and visual things, but I’m not going to sit behind a computer and bang out a script. That’s not my strength,” she says. “I like finding humor in characters. Paul and Stephen are really good at writing dialogue and jokes, but I’m more like, ‘What does she look like? What does she walk like, dress like?’ I’m not like a traditional actress, I just knew I wanted to do something character-based. I had to get it out of my system.” Sedaris had a specific vision for Jerri’s appearance and physical demeanor, starting with her face — overbite, furrowed brows, crossed eyes. Then came the outfits. Jerri wore lots of turtlenecks and long sleeves because “she was riddled with track marks,” says Sedaris, who told the “wardrobe department I wanted to look like I owned a snake.” She imagined Jerri would have a short hairstyle you might see on a professional golfer. An extra dark wig in the original pilot “made me look like Mike Dukakis,” so they added blond streaks. Though Jerri was not particularly attractive, she dressed with flair. “She was no different than Carrie Bradshaw,” says Sedaris.

Comedy Central gave Sedaris, Colbert and Dinello broad creative leeway, and only occasionally asked for script changes — even though Jerri was a nonstop font of offensive language and gloriously profane imagery. The standards were not always well-defined.

The network once demanded that they change the line “that albino stole my midget” to “that madman stole my hobo.” “We were like, ‘You’re kidding. This is where you draw the line?’ Because we’ve said and done some awful, awful things over the years,’” Colbert says.

It helped that Sedaris infused the character with a daffy sweetness that made her oddly endearing, despite her rampant ignorance and a propensity for breathtaking crudeness — like when she proclaimed her bisexuality by saying, “I like the pole and the hole.”

“She was so innocent,” says Sedaris, who currently stars in the “Star Wars” spinoff “The Mandalorian.” “That’s why I think I got away with a lot of stuff. She was just a lovable misfit.”

Dinello always considered Jerri’s flaws relatable, which — along with Sedaris’ gift for comedy — helped create empathy for her. “From a writing standpoint, we always approached Jerri as an animal who wanted to do the right thing, but couldn’t suppress her horrible nature,” he says.

Amy Sedaris as Jerri Blank in “Strangers With Candy.”

(Comedy Partners, Inc.)

Over three seasons produced in less than two years, Jerri learned to read, joined a cult and was sexually harassed, among other challenges.

By the end of Season 3 in in October 2000, Comedy Central was under new leadership and the future of “Strangers With Candy” looked bleaker than Jerri’s college prospects.

“They never officially canceled us, but we saw the writing on the wall, because things just kept disappearing — snack drawers, offices, things like that,” Sedaris recalls. Winona Ryder and Paul Rudd guest starred in what turned out to be the series finale, in which Flatpoint High School faces being turned into a strip mall, a clever nod to “Strip Mall,” the show that replaced “Strangers” on Comedy Central.

But the show continued to air in reruns, and its following grew. Fans rewatched on DVD, perfected their Jerri grimaces and clamored for more tales from Flatpoint. “Strangers With Candy,” a movie prequel, came out in 2006. Now, the series can be streamed on Paramount+ and Comedy Central’s website, for those with a cable subscription.

More recently, Sedaris and company have been approached about a revival. Sedaris says she has dreams of doing a “Strangers” Christmas special. Her friend John Early had an idea for a revival where Jerri goes to college.

Thus far they’ve declined to bring it back, but haven’t sworn off the possibility.

“Nothing has felt right so far,” Colbert says.

Sedaris thinks making a show like “Strangers With Candy” might be difficult in today’s climate because “it’s not PC,” she says, drawing out the last two syllables in Jerri’s high-pitched twang.

Colbert doesn’t entirely agree. “You can make anything you want,” he says. “You just have to deal with people being upset.” (Colbert also goes in and out of “Jerri voice,” a common affliction.)

The late-night host continues to encounter fans of the series — not all of them are dressed in trash bags.

Jack Antonoff was recently on “The Late Show” with his band, Bleachers, and greeted Colbert by chanting, ‘Mr. Noblet! Mr. Noblet!” Colbert fired back, “Shut your dirty little mouth!” — one of Noblet’s most memorable lines.

“If someone says, ‘I really like “Strangers with Candy,”’ I usually say, ‘I didn’t know you were mentally disturbed.’ Our fan base is deeply troubled,” he says. “And I’m happy for them, because I’m deeply troubled too.”