Artists whose work resonates are able to straddle the old and new, pushing us into the future with one hand while pulling from history with the other. Paul Tazewell, the recent Oscar-winning costume designer of Wicked, is just that sort of artist. The costumes he makes become characters all their own, exquisite, finely-wrought pieces that strike a balance between reference and imagination while telling us something about the people who wear them. This much is clear in the current, Tony-nominated production of Death Becomes Her, for which Tazewell designed frothy looks that blend a kind of medieval grandeur with the aesthetic of the late-1940s. Just three weeks after winning the highest honor in film—he says it still hasn’t sunk in yet, but the statue stands tall in his Manhattan apartment— I spoke with Tazewell about our shared Ohio origins, the broader meaning of a career in show business, and the power of a luscious cravat.

———

CHRISTOPHER BLACKMON: The first thing I wanted to mention is that we have a connection. We’re both Black men, we’re both gay, we’re both in fashion, and we’re both from Ohio.

PAUL TAZEWELL: That’s very good. We checked all the boxes.

BLACKMON: You’re from Akron, I believe?

TAZEWELL: That is correct, yeah.

BLACKMON: I’m from Dayton.

TAZEWELL: My uncle lived there for a long time. Now they live in Memphis, but he was there for most of my childhood, actually.

BLACKMON: Has it sunk in that you’ve won an Oscar?

TAZEWELL: I don’t know that I’ve fully wrapped my brain around how it resonates. People have asked me, “Oh, you must still be on cloud nine.” And absolutely, I’m still floating and embracing that acknowledgement and the high of being recognized for what I’ve devoted my life to for the last 50 years. I think that I walk through life downplaying some of it, whether because of disappointment or my own personal feelings about myself. Part of what’s fueled getting to where I am has been working the hardest and not being satisfied with what’s in front of me. On one hand, that has propelled me to work for excellence. On the other, I think it might be an unattainable goal because it’s actually about perfection.

BLACKMON: Right.

TAZEWELL: There are elements of that I try to temper as I look to this glorious moment, really embracing myself and owning all of that joy. Beyond that, and because of where we are culturally, specifically with our country, I have questions about how I can positively affect where we are and how we grow as a society. Those are the big questions that are part of my internal dialogue, really.

BLACKMON: And did that internal dialogue start the moment you got it? Or are these things you’ve been pondering that have just been exacerbated by this new level of fame?

TAZEWELL: More so after the fact. My hope is that my work provides a poetic point of view that is emotionally driven and helps resonate alongside the storytelling I’m doing with the clothing choices. That speaks to the emotional arc of a character and the relationship of one character to another. Within the world of musicals, which is where I really flourish, it’s embracing what music and movement bring to the event and how costumes work alongside those elements to elevate the emotional experience. My job is multi-layered, but I’m always intent on creating visual storytelling that speaks to humanity and dignity. It’s a shared experience that elevates all of us as we create a story that speaks to the human experience.

BLACKMON: When you were up there accepting the Oscar, you said, “This is the pinnacle of my career.” Do you feel like now the real work begins and you can really show what you can do? Or is it a sign of completion, in a way?

TAZEWELL: I hate to say completion because, creatively and artistically, I am not done.

BLACKMON: And I’m not trying to imply that at all.

TAZEWELL: I’m still moving along in the same way I’ve been moving. I’ve been designing Steven Spielberg’s next film. I feel respected, and I’ve always felt respected within Steven’s filmmaking environment and all the people he surrounds himself with. So that doesn’t feel different, and how I’m doing the job is not different. Walking into the next office, meeting somebody I’ve never met before, the feeling of going into that kind of environment may indeed feel different because I have standing behind me the aura of the Oscar. Therefore, that question is answered. I’m confirmed, let’s say.

BLACKMON: One last Oscar question: when they opened the envelope and announced “Paul Tazewell, Wicked,” what were you thinking?

TAZEWELL: Well, when they opened that pink envelope, it’s like an atomic bomb. All the air comes into one space. And then, I was like, “Wait, did I hear my name?” I looked at my sister-in-law, and she was excited. I saw it on her face. Then I had to say to myself, “Paul, you got to get up.” I gave her a big hug. I was congratulating Myron [Kerstein], who was behind me, the editor for the film. Then making my way down the aisle, hoping I wasn’t going to slip on the carpet. Since that moment, what I wake up thinking about is that the first thing that came out of my mouth was, “I’m the first Black man to win the Oscar for costume design.” That was the most important thing I needed to get out to celebrate with the audience, and they were very present with that.

BLACKMON: You got a standing ovation.

TAZEWELL: It was an out-of-body experience, and it was one of the most beautiful—if not the most beautiful—moments in my life of acknowledgement and celebration. Celebrating myself is a challenge, just because of my own personality makeup.

BLACKMON: I’m like that, too. But I want to go back a little bit.

TAZEWELL: Okay.

BLACKMON: What was it like growing up in Akron?

TAZEWELL: My childhood was pretty idyllic. It was definitely middle-class. We lived on the west side of Akron. Grade school was integrated; high school by that time was mostly Black, but still integrated. There was a magnet program, which was all this money put into the school to help integrate, pull other students in. One of the programs in that magnet system was performing arts, and that was what focused my growth.

BLACKMON: So you’ve always known you wanted to go this route?

TAZEWELL: I fell in love with the idea of performance when I was in grade school because I saw this production of Oklahoma and I realized I want to be a part of this kind of creativity. I did community theater. I was always in a play in the drama club. At the same time, around nine years old, I learned to sew. Before that, I was drawing and painting. Crafting was my joy. That was inspired by my mother because she’s an artist and a teacher as well. My grandmother was a painter. So culture and arts and expressing yourself through art had always been part of our upbringing. In ’71, my family built a house in what was indeed an integrated neighborhood, but it was integrated because it was a time of white flight. There were families moving out of the neighborhood and other Black families taking those spaces. But they decided they wanted to build a house designed by my uncle, who’s an architect from Dayton. This neighborhood was very Stand By Me. Everybody on the street looked out for each other. Summers were crazy because we were in and out of each other’s homes, white homes and Black homes all on the same street, playing baseball or hide-and-seek and all those games.

BLACKMON: Yes, come home when the street light comes on.

TAZEWELL: Right. That’s a very cherished time, a time when all of us understood how to relate to other people. That is what’s lost nowadays. I remember being with my cousin who was visiting for the summer and we were talking about dreams. Those dreams that I remember creating with her, those are the dreams I’m living now, which is remarkable. And it came out because of being in a safe space, which is what Akron was at that time. It was also small enough that it wasn’t overwhelming, yet large enough that there was exposure to what was going on outside in other ways, like the tours coming into Akron giving me an opportunity to be inspired by productions I would see. The steps weren’t so big that they felt unattainable. With the performing arts program, that was the first time I went to New York. We traveled as a class, and it was the first time I saw shows on Broadway and fell in love with New York.

BLACKMON: You still had the acting bug at this point?

TAZEWELL: Yeah, yeah. Costumes were great and fun to do, but what I really wanted was to be a performer. I applied to Pratt Institute because it was very important for my family, my parents, that I go to college. I realized I could see myself being a fashion designer and falling back on that if things didn’t work out for me as a performer. I entered [Pratt] in 1982, the same year I graduated from high school. I lived in the dorm, a high-rise apartment building, roach-infested. It was a big, 80s New York experience, and the neighborhood was not that safe. But I managed that year and did a lot of creating. I was in art classes, fashion classes. But the fashion track I was experiencing wasn’t for me; it wasn’t the kind of design I wanted to be doing.

BLACKMON: Right.

TAZEWELL: If I was going to design, I wanted to design costumes. What I found out once I transferred to North Carolina School of the Arts was that the kind of design I was passionate about was telling stories through design. I didn’t verbalize it that way, but indeed that was what was in operation.

BLACKMON: I was just like you, I couldn’t wait to get out of Ohio. It was really an albatross around my neck for a while. So you git to New York, but why leave to go to North Carolina?

TAZEWELL: There was a huge culture shock being alone. I didn’t have any family or good friends there. [North Carolina] was definitely going to be cheaper for my parents, I would be closer to my family. In hindsight, it was the best decision I could have made. I think I was looking for formal guidance in whatever direction I was going to go.

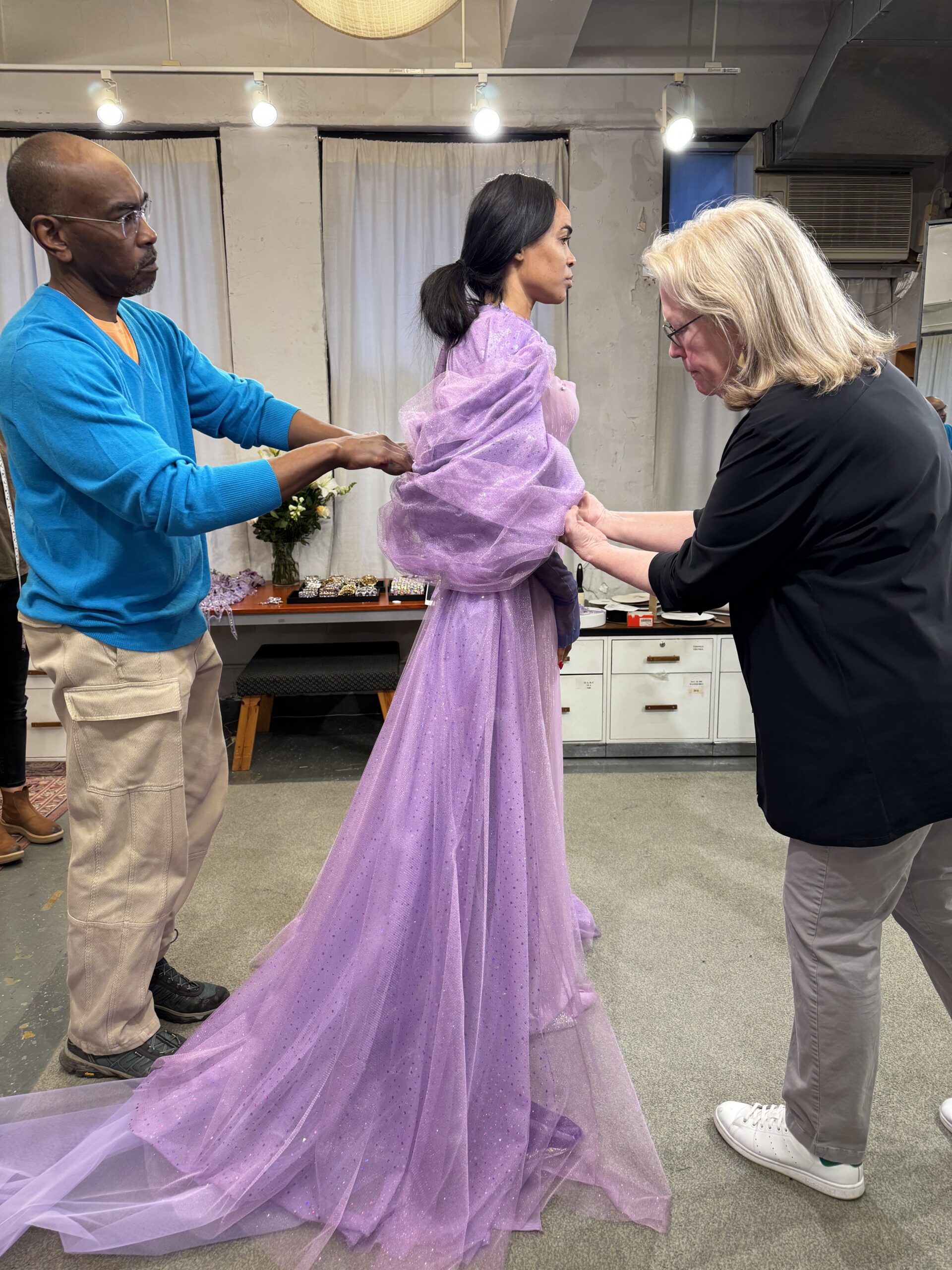

Michelle Williams in fittings for the Broadway production of Death Becomes Her. Photo courtesy of Paul Tazewell.

Michelle Williams in fittings for the Broadway production of Death Becomes Her. Photo courtesy of Paul Tazewell.

BLACKMON: So, what happened between graduation and you working on Before It Hits Home, the play?

TAZEWELL: Well, I had three years at North Carolina School of the Arts, met amazing friends I’m still close with and had the opportunity to really develop as a young designer, meaning it gave me all the skills I needed to design and mount a production. I perfected my costume-making skills just because of how we worked. But at that time, in the 80s, anybody who was becoming successful as a designer was going to undergraduate for four years and then continuing on into a graduate program. I was accepted at NYU with a graduate assistantship, which paid for most of my tuition and some of my housing. I worked with the likes of John Conklin, who’s quite an amazing designer, and Carrie Robbins. In my last year, I met Tazewell Thompson, who is a director. We share a name, but we’re not related, so there’s no nepotism. [Laughs] He directed our final production and I was the costume designer. The set designer dropped out, so I took over the set design as well. Then, I was invited to design a production called Standup Tragedy the year after I graduated. It might’ve been that same year as Before It Hits Home.

BLACKMON: And at the time, in the back of your mind are you still going, “I want to do the acting thing too”?

TAZEWELL: I let the acting go at the end of my second year at North Carolina School of the Arts.

BLACKMON: My editor would be so angry if I didn’t bring up Wicked. How did Wicked come into your life? Do they come to you and say, “Paul, we want you”?

TAZEWELL: Well, I had met John Chu at an event for the Princess Grace Foundation, which had awarded me a fellowship when I was at Arena Stage. I became part of that family, and they follow your career and how you’re developing, so they decided to honor me with a statuette. John was the same, but he was in directing. I knew that he was getting ready to direct his film of In The Heights. I had designed the original production of In The Heights on Broadway with Lin. So there was a direct connection.

BLACKMON: We’re talking about Lin-Manuel Miranda?

TAZEWELL: Lin-Manuel Miranda, yeah. That gave me an opportunity to personally connect with him. But he didn’t say, “I’ve got this potential gig,” because it was many years before, and definitely before West Side Story. I think because of my visibility with Hamilton, and then definitely having worked with Steven on West Side Story, I became a notable entity as someone who was a costume designer for film. And then when Wicked came up—Marc Platt and I had worked together on Jesus Christ Superstar in concert, starring John Legend for NBC. He was one of the producers.

BLACKMON: Another Ohioan.

TAZEWELL: Yes, he’s from Springfield. So Marc knew of my work, knew what it was like to work with me. John actually called me, or an agent must have called me. I knew from past experience that it was probably important for me to show what my point of view might be if I was designing Wicked. It was really using it as a conversation starter so he could understand how I visualize and I can better understand what he gets excited about. We had a long discussion and then, maybe a couple of days passed, and they said they’d like me to join the team.

BLACKMON: How many costumes did you end up designing?

TAZEWELL: I never remember numbers, but it was a very significant amount, definitely in the thousands. I was designing both films at the same time because really, the two films are the first act and the second act, the continuation of the story. My intention was to create a fully realized world that was different and new. We were going to be on real sets that were fully realized, with real people, so we weren’t talking about CGI, except for the animal characters. It was a godsend that we ended up going to London to film, because the pool of makers is huge. It’s also been part of their culture for such a long time. So when you have the ability to invite hand embroiderers and beaders and hand weavers and knitters, machine and hand-knitting and other textile manipulators, as well as fantastic dressmakers and tailors and fabric printers—we had them all underneath the same roof, basically. We were in a couple of different warehouses, but it was all five minutes away. Having access to that talent base was extraordinary. It’s just such a huge privilege, one that I don’t know will be recreated, but that was what it took to be able to dig deep into couture work.

BLACKMON: Yes. Isn’t couture so beautiful?

TAZEWELL: Oh, yes. Being able to tap into that was really what defined what Wicked is as a design, it had all of that detail. For me, and for the production designer, Nathan Crowley, it was important to create everything that was going to be visual. I’ve said we designed down to the far corners. I was designing into the seams because we needed to develop what the rules were for Oz, for the people of Oz, how they see their world and what inspires them to dress themselves the way they do. That then needed to play to an audience that was already fans of Wicked. So there are a number of different elements we’re trying to orchestrate into one cohesive world that makes sense for these two films. Being there on the ground—14 hours a day, at least six days a week—was my joy spot.

BLACKMON: In that moment, when you’re dealing with all of the stuff you were just talking about, you must have known that this film was going to go the distance.

TAZEWELL: I knew it was something very special, really extraordinary, because I was excited about my own work. I get a buzz, there’s a tingle that happens, just something physical that tells me this is going to work. You see a clip of something, maybe looking at dailies, and see how all the different elements come together. That’s what I always look for.

BLACKMON: So, Paul, two questions before I let you go. We’ve got to talk about your Oscar look. Dolce & Gabbana, correct?

TAZEWELL: That’s right.

BLACKMON: How did it come about?

TAZEWELL: It’s a Dolce & Gabbana silk shirt that has a cravat built into the collar, long enough so that I could wrap it around. From Hamilton, I know how to tie a cravat. The lushness of that drape speaks to me. That was what was so important as I was choosing what to wear for the Oscars—something that would reflect what I do as a costume designer, my intent on very pristine tailoring, and then also fit, which is different from fitting somebody else. It checked all those boxes.

BLACKMON: How heavy is the Oscar?

TAZEWELL: Oh my gosh. You could build some muscle with that. I was carrying it all night. Then. when I would set it down, I was very aware of where it was.

BLACKMON: Where is her permanent home?

TAZEWELL: Well, right now it’s on my sideboard credenza in my living room, in my apartment in Brooklyn. It’s right across from my couch. So when I sit on the couch, that’s basically all you see. The other awards I’ve received, my Tony for Hamilton and the Emmy I won for The Wiz for NBC, they’re on a shelf in my guest room, but I need to create an actual display. I’ve heard about people who put them in their bathroom or use it as a doorstop. But I don’t have that relationship to this kind of honor. This is indeed one of the most important things that’s happened in my life and I want to cherish it and raise it up and be respectful of it. I will indeed get its position of glory, I’m just not quite sure where that’s going to be.

BLACKMON: You just need to do a spoken word album and then you’ve got an EGOT.

TAZEWELL: Wouldn’t that be exciting? That would be very exciting.

Content shared from www.interviewmagazine.com.