It’s hard to imagine a stranger pairing: Lindsay Anderson, the pioneering director acclaimed for his provocative leftwing critiques of postwar Britain, and Wham!, the young pop duo behind Wake Me Up Before You Go-Go and Last Christmas.

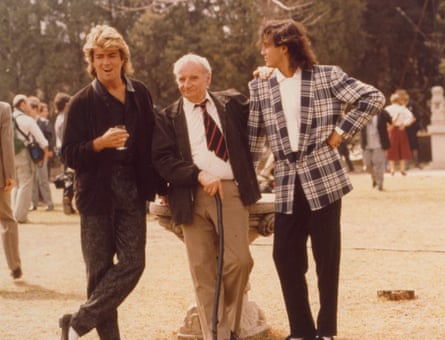

Yet the two parties came together in 1985, when Anderson, then 61, was hired to direct a documentary about George Michael and Andrew Ridgeley’s groundbreaking tour of China, which made the 21- and 22-year-olds the first western pop act to play in the country.

The collaboration ended in tears. The finished product failed to impress the group and Anderson was fired. His film has never been seen publicly; a later anodyne edit, released after Anderson’s exit, is almost impossible to see today. Glimpses of the footage can be seen in the Netflix documentary on Wham! released this week.

Anderson kept hold of his cut, entitled If You Were There…, after Wham!’s Isley Brothers cover, but also echoing Anderson’s best-known film, If.…, which won the Palme d’Or in 1969. After his death in 1994, at 71, it surfaced in his archives at the University of Stirling. Twelve years later, the university organised a public screening, only for it to be blocked by Michael’s management. The university and Michael then agreed that the film could be seen privately, in Stirling’s library, by arrangement. I went there this week to do that.

It’s easy to see why the film was not to Wham!’s taste. It was rejected for being more about China than Wham!, a complaint that holds true. Anderson is far more interested in what is going on around Wham! than in the band themselves, or the two concerts they gave, in Beijing and Guangzhou. But given the opportunity to observe China just a few years after the country had started to open up to the world, Anderson can be forgiven for wanting to take in the surroundings. His keen observational eye picks out extraordinary faces and details of street life amid the Mao jackets and endless bicycles; there are intriguing interviews with Chinese people talking about music and their aspirations.

But there is also plenty of Wham!. One senses Anderson had some sympathy with the band for what the tour entailed – the many meetings and banquets with Chinese officials, unrelenting press attention, rehearsals in dreary rooms. With their preternatural glamour, Michael and Ridgeley seem almost as out of place making small talk at a party hosted by the British ambassador as they do touring the back streets, yet they are always polite and obliging.

Anderson includes just four songs from the concerts and shows only one performance in full. He cuts away to street scenes during Freedom, while, in a bravura sequence, Everything She Wants – with its refrain of “Work to give you money” – is intercut with markers of early westernisation: boxes of Japanese and German goods arriving in the streets; a woman at a hair salon browsing a catalogue of western styles; shoppers examining ties and watches.

Wham! might well have preferred Anderson to focus on their performance rather than essaying a critique of embryonic Chinese consumerism. It would also be understandable if they had balked at the restaurant scene in which we are shown images of flayed dogs, a young deer presumably about to be slaughtered and a snake being skinned alive.

Perhaps the film’s standout sequence comes towards the end. David Baptiste’s saxophone intro to Careless Whisper drifts in as the camera pans across the Pearl River in Guangzhou; boats sail by, a woman sells shoes, a child jumps up in a barge and people cross a bridge, silhouetted against the setting sun. Then, just as Michael is about to start singing, Anderson cuts to him.

The tour itself was a success – and the film played a significant part in that. The shows were designed to generate enough publicity to allow Wham! to crack the US market – a strategy that paid off handsomely. The film was required by Wham!’s record label, CBS, as a condition for lending the group the money for the trip.

It seems bizarre that Anderson was hired in the first place. According to Wham!’s manager, Simon Napier-Bell, in his book I’m Coming to Take You to Lunch, Anderson was chosen because he had experience in features – it was hoped the film might get a cinematic release – and documentaries, which it was thought might be required for a tight 10-day shoot. But Napier-Bell, whose father had worked with Anderson, knew the director could be inflexible and ill-tempered. Ridgeley describes the choice in his autobiography as “absolutely bonkers”. He suggests Napier-Bell wanted Anderson to lend the project “gravitas and artistic credibility” and that Michael admired Anderson’s political outlook.

Anderson needed the work. “He was at a low point in his career – Britannia Hospital, in 1982, was a flop, so for the first time in his career he had to be a director for hire,” says Karl Magee, the archivist at the University of Stirling.

In Anderson’s diary, which is held in the archive, he writes on arrival in China: “I have no interest whatever – I’m sorry to say it – in China and its millions … I have no interest in Wham!, either … Essentially, I am ‘doing this for the money’.”

But natural curiosity seems to have got the better of him. In a revealing letter, written after he was fired, he says he had no illusions about the job, but “when we started going through the material, finding the shape and starting to create a film, I found myself quite unable to resist the temptation to behave like an artist”.

The trouble was that he had met his match in Michael, a fellow creative brimming with confidence and ambition, even in his early 20s. The Stirling archives contain two letters from Anderson to Michael, the first reassuring him that a decent film will be made, despite a “staggering amount of rubbish in our rushes”. The second was written as the project reached a “dangerous crisis”, with Anderson warning that the producers were having misgivings and hoping to get Michael to see his latest version. There are no replies from Michael in the files.

The exact sequence of events leading to Anderson’s dismissal are not easy to discern from his papers. Napier-Bell wrote that the first cut of the film was “achingly boring” and that Michael thought a second version appeared to be “scornful” of Wham!.

“It should have been possible for Lindsay – or any director with an ounce of compromise in him – to have adjusted it to what Wham! needed as a promo tool,” says Napier-Bell today. “But he obviously felt it beneath him to compromise with two upstart kids. He was always a difficult old bugger, full of guilt at his own public school education, but suffering from the superiority it had given him.”

Michael then became involved in shaping the film into what became Wham! in China: Foreign Skies. Shown to 72,000 fans at Wham!’s final concert in 1986 and released on VHS, it has never been made available on DVD and secondhand copies are scarce. (It can be found online, but not on legitimate streaming platforms.)

Foreign Skies is far more snappily made – a martial arts sequence that Anderson put into a solemn interlude featuring Chinese traditions is cut to Bad Boys, for instance – and keeps the focus on the band and their experience. Anderson thought it was “inept and badly crafted”, but his name stayed on it; it is one of just nine features credited to him.

The fate of If You Were There has been to lie in the archives, denied a public release. Anderson didn’t help his cause when news of his exit broke and he told the press that Michael was “a young millionaire with an inflated ego”. He was even ruder in private. One letter says: “Though talented in his very limited range, [Michael] is a spoiled, conceited dumbbell.”

Napier-Bell says: “He was certainly very unhappy that he was fired and that his version of the film was never seen. On the other hand, he was ridiculously rude to, and about, George and Andrew. It was as if he was testing to see how far he could go. And the answer, with someone like George, was: not very.”

Michael continued to block the film’s release until his death in 2016 and there has been no change in policy since. A lawyer for his estate said they had been unable to discuss the Guardian’s request for comment with Ridgeley, but that it was the estate’s general policy not to comment on “confidential business matters”.

Viewed now, Anderson’s film more than lives up to his description of it as “a movie of some originality, charm and quality”. It seems a pity that one of the few films made by such an acclaimed and interesting figure – and a document of China at a historically fascinating juncture – remains unseen.

Perhaps Anderson, to paraphrase one of Wham!’s most enduring hits, wasted the chance he had been given. Yet the band’s custodians might care to call back to mind the silver screen – and all its sad goodbyes.