On the Shelf

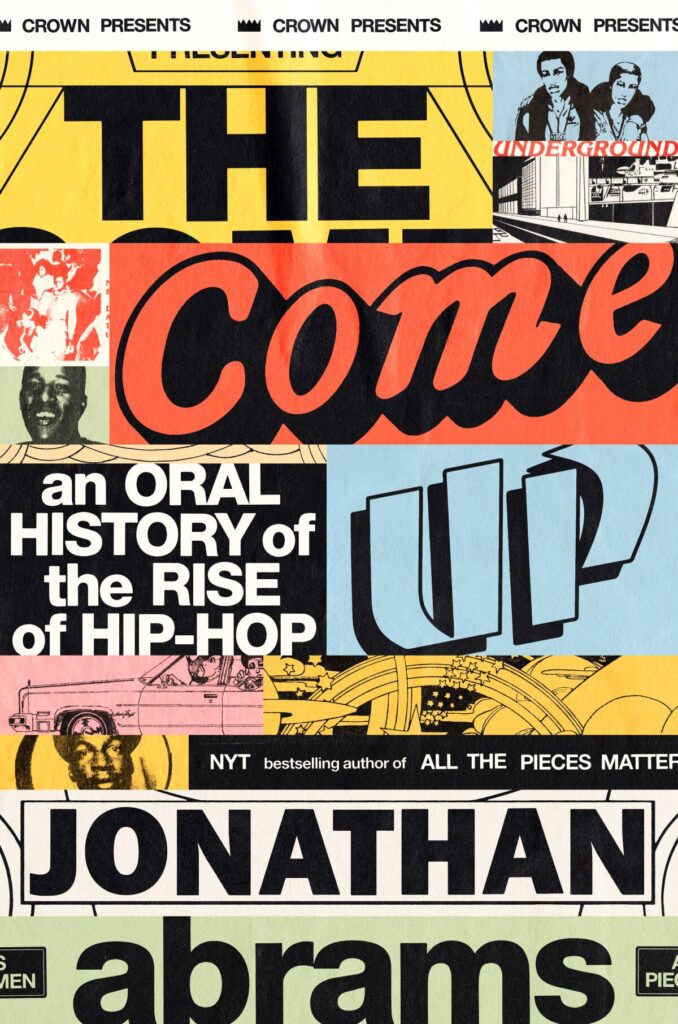

The Come Up: An Oral History of the Rise of Hip-Hop

By Jonathan Abrams

Crown: 544 pages, $35

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Heated words have been exchanged and egos bruised over the question of where hip-hop was born (most accurate answer: the Bronx). Jonathan Abrams touches on such matters in “The Come Up: An Oral History of the Rise of Hip-Hop.” But he also does something far more rewarding, pinpointing a series of cultural detonations, or chain reactions, that started in New York, jumped to Los Angeles and spread to anywhere and everywhere that had creative young people with chips on their shoulders.

Some of the artists and businessmen in these pages became stars, including Ice Cube, Run-DMC, 2 Live Crew and Ice-T. Most of them didn’t, and they’re the ones who provide the most insight into what these formative years were really like. They have less ego to protect. They speak from love and from frustration and from dreams never reached — or even reached for. LL Cool J, a pioneer who also managed to become a superstar, recently took a young DJ to task for suggesting hip-hop’s architects were “dusty” and “not living good.” “The Come Up” gives these artists a well-deserved chance not merely to shine but also to tell readers how it all happened.

Abrams takes it back to 1973, when a Jamaican immigrant named Clive Campbell threw a fundraising party for his little sister in the West Bronx. Standing before his massive sound system, he used two record players to isolate drums between sections of melody. These patterns, better known as breakbeats, would become the DNA of hip-hop. Campbell, better known as DJ Kool Herc, never got rich off his innovations. But he did help birth a multibillion-dollar industry. Soon, his peers, including Grandmaster Flash, were using turntables as musical instruments, and the young men and women saying rhymes over the beats became, more often than not, the stars of the culture.

Oral histories rise or fall on reporting and editing. Abrams, who has previously written books on the television series “The Wire” (“All the Pieces Matter”) and high school basketball stars who jumped to the NBA (“Boys Among Men”), excels at both. He knows whom to talk to and he knows what questions to ask them. He weaves these interviews together to create the illusion of conversation — with one another and with us. And when it’s time to reset the context he jumps in, quickly and concisely, to redirect the flow.

Sometimes he even lets them argue. Backers of Public Enemy are adamant that Russell Simmons, who co-founded the first powerful hip-hop label, Def Jam, had no interest in the firebrands. Not true, says Simmons, whose voice is heard throughout the book. He was onboard from the beginning. To which P.E.’s Professor Griff says: “Russell was into R&B and cocaine. He ain’t into no Public Enemy. Ain’t a radical bone in Russell Simmons’s body.” (For the record, both men have checkered pasts: Simmons has been accused of rape by multiple women and Griff ignited his own firestorm with a string of antisemitic comments. Abrams acknowledges all of this, but he still uses them prominently in the book.)

The members of Goodie Mob, including (from left) CeeLo Green, Big Gipp, Khujo and T-Mo, and broadened the horizons of Southern hip-hop.

(Taylor Hill / Getty Images)

Abrams spends an appropriate amount of time in New York, the undisputed cradle of hip-hop. The Sugarhill Gang showed rap could be a hit on record with 1979’s “Rapper’s Delight,” even if they lifted huge chunks of rhyme from Grandmaster Caz, of the underground legends the Cold Crush Brothers, and many artists of the time viewed it as a novelty record. The act that grabbed everyone’s attention was Run-DMC, a trio of hungry Queens kids who blasted off with a combination of booming beats, loud guitars and street fashion.

“Up until that time, there was nobody representing the streets, styling themselves like the streets,” DMC tells Abrams. Run-DMC was a shock wave, a hip-hop group that crossed over to the mainstream with a borderline punk sound. They put Def Jam on the map when the label was still run out of an New York University dorm room by Simmons and a student named Rick Rubin.

Abrams returns to New York throughout the book, but he also does what good reporters do. He hits the road, the only way to do justice to hip-hop’s explosive popularity. That means Los Angeles, of course, where he tracks the rise of gangsta rap (and acknowledges that the subgenre really started in Philadelphia, with Schoolly D). He spends extensive time in the South, providing a detailed account of how Florida’s 2 Live Crew exposed the folly of obscenity laws and how homegrown scenes gradually developed in Atlanta, Houston and beyond.

Jonathan Abrams tells the full origin story of hip-hop, and more, in “The Come Up.”

(Nicola Borland Photography)

Each locale has its own pioneers, many of whom the casual fan won’t have heard of: Houston’s K-Rino, Memphis’ DJ Spanish Fly, Atlanta’s Mojo. Such artists helped lay the groundwork for regional scenes that would gain national prominence. Abrams gives them their due, reminding the reader that hip-hop history is littered with innovators who never got rich.

All told, it’s an extraordinary tale, the story of how a grassroots culture created itself from the streets and became an international force. To his credit, Abrams doesn’t just talk to the architects. He also gets input from the stonemasons, the contractors and the other heavy lifters. It’s the oral history hip-hop deserves as its beat goes on.

Vognar is a freelance writer based in Houston.