“Omar,” the new opera by composers Rhiannon Giddens and Michael Abels, finds its strength in the simplicity of prayer.

The work, which is too fluid to be classified in discrete musical or dramatic genres, is derived from the autobiography of a West African Muslim scholar named Omar Ibn Said, who was abducted and sent to America, where he was enslaved in the Carolinas. His 1831 memoir, written in Arabic, leaves behind in veiled form the spiritual journey of a man who, brutalized by history, managed to hold on to the faith of his people.

This Los Angeles Opera production, which opened Saturday under the direction of Kaneza Schaal at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, follows the lead of Giddens’ libretto in focusing on Omar’s inner light. The protagonist’s saga is outlined in uncluttered scenes that move from what is now Senegal through the harrowing and deadly Middle Passage to an auction block in South Carolina, which leads directly to the abyss of slavery.

The nightmare that Omar wakes up to defies comprehension. Shackled to strangers he cannot understand, he is deprived of the solace of shared language, heritage and community. He has only his religion and a single, unanswerable question: Why?

Jamez McCorkle walks onto the stage in shorts and an Alice in Chains T-shirt before donning the attire of Omar, a role he brings to life in all its spiritual magnificence. The production foregrounds that this is an artistic interpretation of historical material — the present reaching back to the past in an attempt at mutual understanding.

In her exploration of the music of the Black diaspora, Giddens, a two-time Grammy winner who trained to be an opera singer at Oberlin Conservatory, has channeled archival research into long-lost forms through the filter of her own instincts in country, folk and jazz. Her mode is syncretic and pluralistic. She has expressed reservations about the term Americana, not wanting to be limited by terminology. But of all the music being composed today, hers might be the clearest expression of the American experiment, in all its varied hues and tonalities.

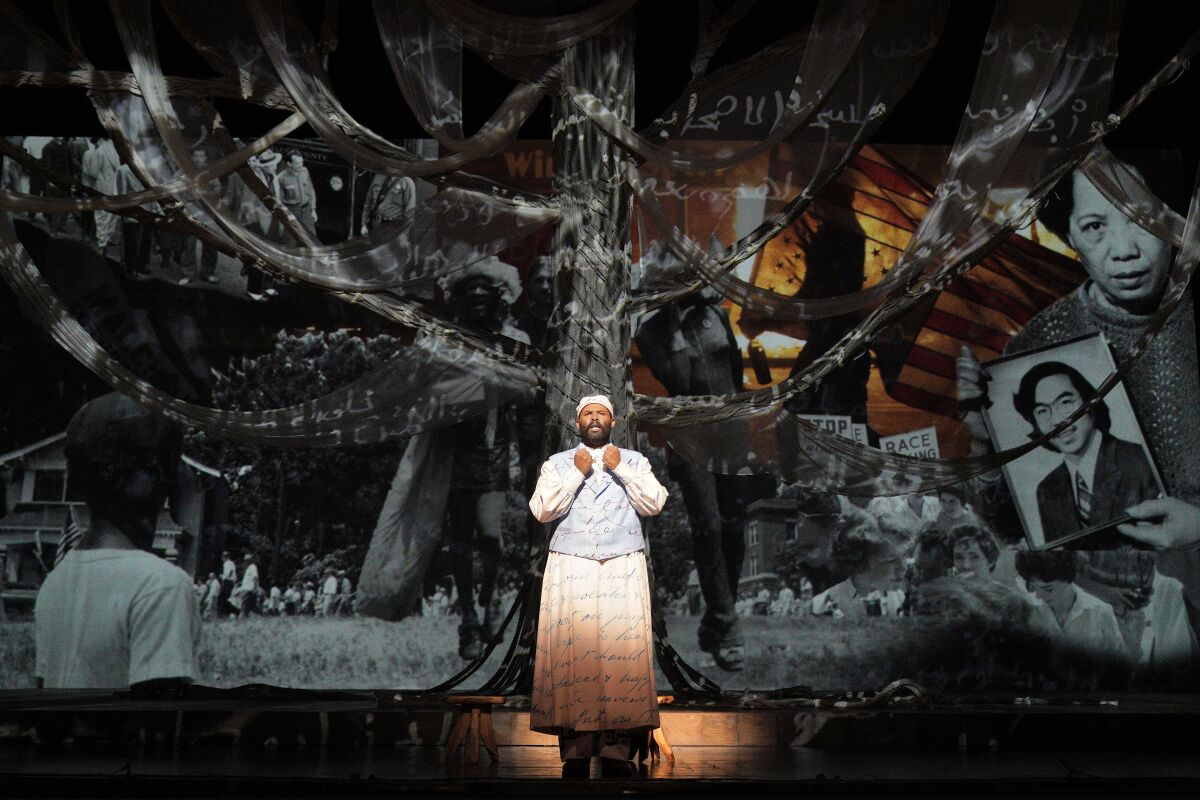

The inwardness of McCorkle’s Omar has an overwhelming gravity. He kneels in prayer, seeking insight and direction. His clothes are covered in Arabic script, the same script that is projected onto scrims and screens. The word is holy to him. Writing offers a path of redemption from meaningless suffering.

McCorkle, who originated the role of Omar at the opera’s premiere this year at Spoleto Festival USA, has a tenor that vibrates with somber glory. Even when the libretto feels skeletal, McCorkle supplies an emotional heft. The meditative sincerity of the performance left me with my head bowed.

As Omar’s mother, Amanda Lynn Bottoms brings a maternal devotion that transcends the grave. After her death, she stays close to her son, reassuring him that his hardship is not without a divine plan. Bottoms’ singing, otherworldly in its beauty, carries the loving wisdom that allows her son to endure his abominable trials.

Amanda Lynn Bottoms as Fatima in L.A. Opera’s production of “Omar.”

(Cory Weaver)

Playing an enslaved woman who tries to help Omar early in his journey and later reunites with him under less severe circumstances, Jacqueline Echols endows Julie with a sublime radiance. Giddens keeps the nature of this invented character’s relationship with Omar implicit, thereby maintaining the story’s spiritual tenor, a quality Echols serves with the haunting purity of her soprano.

The first act of “Omar” has some difficulty hitting its stride. The spareness of the libretto takes some getting use to. Giddens’ lack of experience in dramatic plotting reveals itself in the early going. What’s more, the lyrics of some of the arias are noticeably less original than the music behind them. The singers, however, alchemize everything into the most hypnotic sound.

The second half begins with a visual coup. Omar, now in prison, is poetically encircled by reams of his writing. In the Fayetteville, N.C., jail after escaping abuses on a South Carolina plantation, he has no idea that his life is about to change.

Owen (Daniel Okulitch), a kindlier plantation owner, is led to the prison by his daughter, Eliza (Deepa Johnny), who is moved by Omar’s piety and implores her father to buy him and take him to their home. The words Eliza sings are banal, but the sound behind them is the force of destiny.

The contrast in plantations is schematically drawn. (The production undercuts this somewhat by having Okulitch play the earlier cruel plantation owner who takes sadistic pleasure in breaking Omar, but it’s as if Omar has been sent from hell to a resort spa.)

It is understood that Owen’s relative goodness is partly an effort to quell anti-slavery sentiment. It is also understood that his interest in Omar has much to do with the prospect of converting an educated Muslim to Christianity.

But some may feel that the warm welcome Omar receives from the enslaved workers at Owen’s plantation effaces the harsher reality of the character’s circumstance. A planned frolic that features joyful dancing to the compulsive rhythms of a string band forgets that the conditions behind this festivity aren’t volitional.

But the focus is purposely on Black survival. Just as the Greek tragedian zeroed in on moments of choice and free will in the plots of characters circumscribed by fate, so Giddens and Abels look for moments of freedom in the lives of characters denied this basic human right.

Jamez McCorkle as the title character in L.A. Opera’s West Coast premiere of the Rhiannon Giddens-Michael Abels “Omar.”

(Cory Weaver)

The second half deepens as Omar’s path and that of the opera itself become clearer. The score invokes at times George Gershwin’s indelible score for “Porgy and Bess,” but it’s not following in the same tradition that led inevitably to Terence Blanchard’s searing “Fire Shut Up in My Bones,” the first staged work at New York’s Metropolitan Opera written by a Black composer.

Abels, a film composer known for his eclectic scores for the Jordan Peele films “Get Out,” “Us” and “Nope,” is clearly comfortable in inhabiting the hybrid zones of music drama to which Giddens naturally gravitates. “Omar” treads a line between staged concert, full-scale opera and religious service.

The imaginative spryness of the design team is as instrumental to the production’s success as the nimbleness of conductor Kazem Abdullah, who expertly guides the orchestra through African, Muslim and American styles. Visually and acoustically, the earthiness of the work is given an ethereal lift.

“Omar” invites audiences to remember the lives of all those whose stories were unwritten by considering the miracle of one who managed to transmit his own. This is painful material but also triumphant, despite the impossibility of a happy ending. Omar lives again, thanks to the unconquerable power of his words, now borne aloft by the music of history.

‘Omar’

Where: Los Angeles Opera at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, 135 N. Grand Ave., downtown L.A.

When: 7:30 p.m. Saturday and Nov. 2, 5 and 9; 2 p.m. Oct. 30 and Nov. 13.

Tickets: $15-$199

Info: (213) 972-8001, laopera.org

Running time: 2 hours, 45 minutes (one intermission)