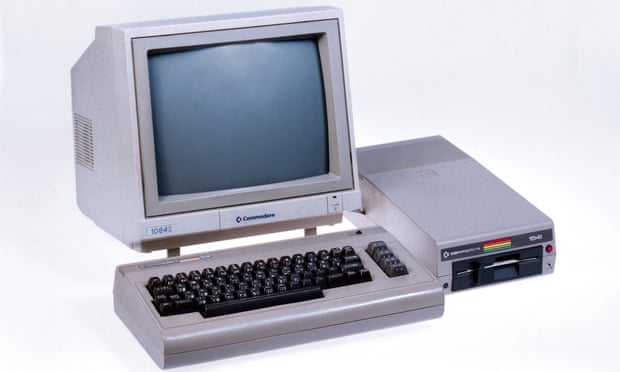

For a period between the winter of 1983 and the summer of 1986, my life was completely dominated by the Commodore 64. The seminal home computer, launched 40 years ago this month, featured an 8-bit microprocessor, a huge 64k of memory and a set of graphics and sound chips that were designed by the engineers at Commodore’s MOS Technology subsidiary to power state-of-the-art arcade games. That didn’t happen. Instead, Commodore president Jack Tramiel ordered the team to build a home computer designed to smash the Atari XL and Apple II. So that’s what they did.

I didn’t know any of this when my dad brought home a C64 one afternoon a year after the launch of the machine. Ours came with a Dixons cassette featuring a number of little demo programs and a copy of Crazy Kong, a version of Nintendo’s Donkey Kong, written entirely in Basic, and fairly mediocre. I played it to death anyway. That Christmas, I asked for some actual good games, which would include the legendary multi-stage shooter, Beach Head, the inventive platformer, Lode Runner and the footie game International Soccer, one of the few titles to come on a cartridge rather than a cassette tape.

At that time, programmers were still getting to grips with the machine. Offering twice the memory of most rivals, its hardware could also handle seamless scrolling allowing natural movement around larger game maps, and eight multicolour sprites on screen simultaneously. The superlative SID sound chip acted as a built-in synthesiser, allowing specialist computer musicians such as Rob Hubbard and Martin Galway to produce chip music of great beauty and complexity – some of which was celebrated at a Commodore 64 orchestral concert a few years ago. We take it for granted now, but this was also a plug-and-play machine – unlike many other computers of the era, it didn’t need an adaptor to connect to your TV, or a special interface to plug in a controller. It was ready, right out of the box, like a video game console: a vital step forward for home computing.

During my first months as a C64 owner, I was buying early games magazines such as Personal Computer Games and Computer and Video Games, obsessing over news and previews, writing endless wish lists. A new nextdoor neighbour moved in: his name was James (he’s now better known as the actor Jimi Mistry) and he also had a C64. We got to know each other by swapping games – I remember he had the beautiful martial arts adventure Karateka by Jordan Mechner, who would go on to make the Prince of Persia titles, and I was amazed by its atmospheric cinematography. It hinted at a future in which interactive stories would be more than “knight saves princess”.

1984 was the explosive year. Games such as Bruce Lee, Boulder Dash, Summer Games and Pitstop II came along in quick succession, showing the visual and tonal variety of C64 titles. It is difficult now to sum up the impact of seeing the ultra-smooth character animation in spy game Impossible Mission or hearing the synthesised voice in Ghostbusters. I became part of a little collective of C64 owners in my town; we’d swap games, read each other’s magazines, and go on software hunting field trips around Stockport town centre – Debenhams, Dixons, WH Smith, Boots, a couple of specialist computer stores down little sidestreets. When Mastertronic started selling budget games in video rental shops and newsagents, our search widened. My mum used to take me to Wythenshawe library, where they rented out games for 10p a week. You could also submit cards requesting new titles. The staff there got to know me pretty well.

I loved the fluidity of C64 games – the genres we now know really well were still blurred and malleable. The Sentinel was a puzzle game, but also sort of sci-fi horror; Spindizzy was an exploration game, but also a puzzler; Gribbly’s Day Out was a platformer but also an arcade adventure. These games built surreal, yet geometrically naturalistic worlds in an early sort of 3D, the sharp pixel visuals cleverly suggesting reflective surfaces and flowing water.

The game I played most with my dad was Leaderboard, a golf sim set on a series of island courses that would draw on screen as you watched. I can still vividly remember sitting with my dad on our gaming bench silently watching the fairways block out in front of us. It was programmed by Bruce Carver, one of the star creators of the era, who also made Beach Head and Raid Over Moscow. Carver was one of a generation of programmers and designers who really started to develop a theory and practice of how to create compulsive home video games. “There’s a lot of thought given to what’s going to be the most playable screen,” he said in an interview with Computer! magazine in 1985. “You want to take that user to the point where his hands start getting sweaty, and he’s always making decisions on what he’s going to be firing at, or what he’s going to do.

“If you just always have the same thing for him, he’s going to get bored really quickly, so you make his mind work, you give him options … We try to very subtly put those all through the game, so it’s not really apparent, but it retains the interest for a long time.”

This was important because we were seeing a definitive split, between the turn-’em-over-quick philosophy of the arcade, and the longevity of home console and video game design. Between 1985 and 1987, the C64 was in its absolute pomp. Titles such as Wizball, Sid Meier’s Pirates!, International Karate and The Last Ninja, were prescient indicators of the games industry to come, with sprite animations, immersive worlds and complex narratives.

Of course, this kind of thing was happening on the Spectrum too, but I really associate that machine with the early 1980s. Its indie aesthetic, the bizarre Python-esque humour, the glitchy, splattered visuals – they all recall the era of alternative comedy, experimental synth pop, recession and unemployment. It was counter-cultural and idiosyncratic. The Commodore 64, however, is the mid-80s: sleek, flashy visuals, MTV and pastel-coloured positivity. In many ways, it was the absolute best indicator of where games were going: toward the mainstream. And in technological terms, the Spectrum was a dead-end, but the C64 led us to the Amiga, laying the foundations for the era of point-n-click adventures, turn-based strategy games and expansive adventure platformers. Its formative Compunet online system and thriving demo scene also fed the games industry with talent, ideas and a sense of community for years to come.

The games I played on the C64 during that era of my life have left an indelible mark on me – perhaps because they were practically all I thought about during those impressionable years. Paradroid, Thing on a Spring, California Games, Dropzone … these experiences provided access to rich little worlds, captured in a multitude of colours on the tiny CRT TV in our kitchen. They were where I wanted to be and possibly, in a lot of ways, where I still am.

The wonderful book Commodore 64: A Visual Compendium, an intelligently curated selection of C64 screenshots and imagery, contains a quote from graphic artist Paul Docherty that really captures the era: “Painting in pixels was never more magical for me than when I was sitting in a darkened room with just a joystick hooked up to the C64 and the cathode ray tube glowing in front of me.”

He was talking about the experience of making games for the machine. But like millions of others at that time, I felt the same about playing them.