“Everybody’s very happy, ‘cause the sun is shining all the time.

Looks like another perfect day. I love L.A.”

— Randy Newman

Ever since its founding in 1781, Los Angeles has been labeled as the City of Angels. But the future president of the United States has a far less heavenly opinion, predicting in a fiery campaign address that the “sinful” city will be destroyed by an earthquake “in divine retribution.”

Days after the remarks, a massive quake devastates most of Los Angeles and many of its landmarks, including downtown’s Bonaventure Hotel, Union Station and the Santa Monica Pier.

After amending the Constitution to allow him to be president for life, the commander in chief issues a directive that separates Los Angeles from the rest of the country, transforming it into a deportation center for those found “too undesirable or unfit” for the new “moral America.”

Cut!

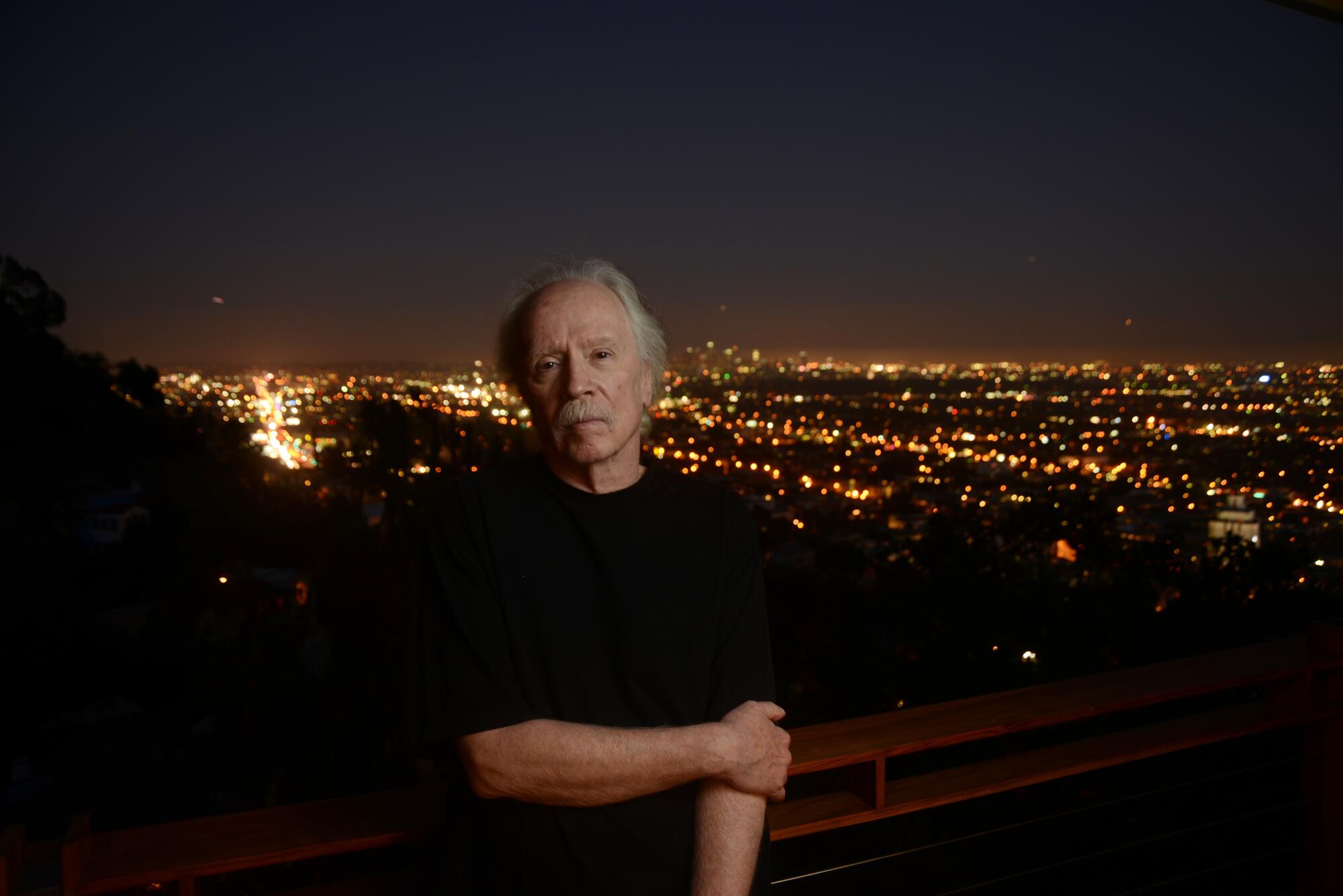

To be clear, everything you’ve just read is fiction. The above scenario is the setup for John Carpenter’s 1996 film, “Escape From L.A.” which presents a satirical, post-apocalyptic view of future Los Angeles.

John Carpenter directed and co-wrote “Escape From L.A.”

(Kyle Cassidy)

Carpenter, best known for creating 1978’s “Halloween,” which launched a fresh new wave of horror movies, belongs to a legion of filmmakers who’ve put Los Angeles in their creative crosshairs, aiming their wrecking balls at its palm trees, skyscrapers and world-famous landmarks.

From 1953’s “The War of the Worlds” through 1982’s “Blade Runner” and 2013’s “This Is the End,” vast areas of the city have fallen victim to a variety of calamities, including earthquakes (“Earthquake,” 1974), tornadoes (“The Day After Tomorrow,” 2004), comets (“Night of the Comet,” 1984) and underground eruptions (“Volcano,” 1997).

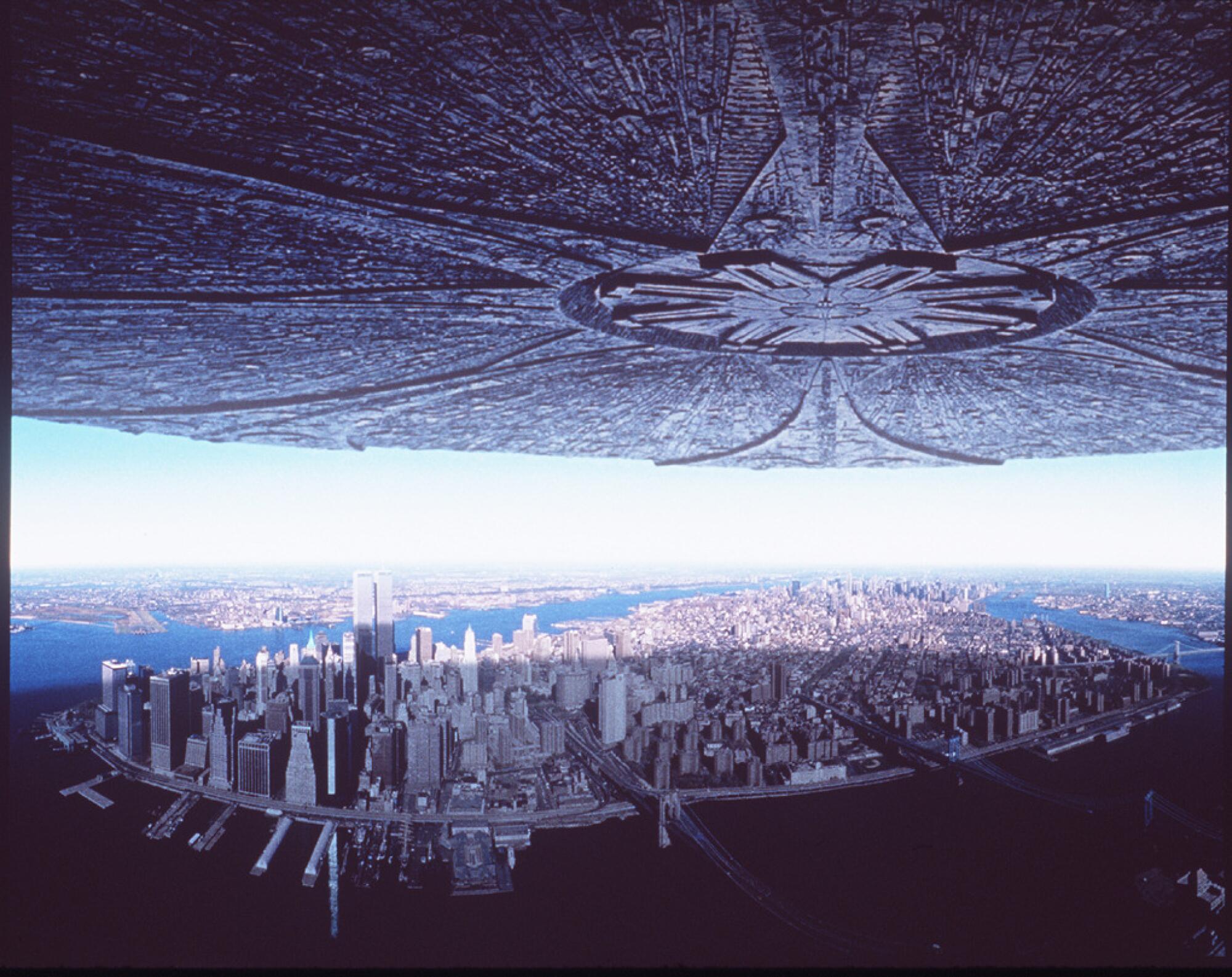

Giant mutant ants invade Los Angeles in “Them!” (1954). A shower of frogs falls from the sky onto San Fernando Valley residents in “Magnolia” (1999). Aliens from outer space appear to have a particular disdain for Los Angeles, as evidenced by “War of the Worlds,” “Independence Day,” “Battle: Los Angeles” and “Skyline.”

In “Independence Day,” alien invaders target and destroy Los Angeles.

(©20th Century Fox.)

“Blade Runner” — “the official nightmare of Los Angeles,” according to filmmaker and critic Thom Andersen — depicts a dark, heavily polluted urban center with flying vehicles and residents drenched in a constant downpour of acid rain.

In “Los Angeles Plays Itself,” his 2003 documentary chronicling the portrayal of the city through cinema history, Andersen aims his own wrecking ball. The film’s narrator quotes the late Mike Davis, a noted historian and urbanist, when he says that Hollywood “takes a special pleasure in destroying Los Angeles — a guilty pleasure shared by most of its audience.”

Films depicting the fall of Los Angeles have long been a reliable draw for movie audiences. And, with techniques ranging from detailed models to extensive CGI, the sequences of destruction have offered a signature showcase for the industry’s visual effects artists.

Take “Earthquake,” Universal Pictures’ disaster epic with an all-star cast topped by Charlton Heston, Ava Gardner, Richard Roundtree, Lorne Greene and George Kennedy. When the movie premiered in 1974, theaters presented it with a special speaker system called Sensurround which made auditorium seats vibrate during sequences of ear-shattering mayhem.

The movie opens with a bird’s-eye view of Los Angeles’ picturesque skylines, reservoirs and grassy hillsides before the bold-faced title appears, accompanied by ominous music courtesy of legendary composer John Williams. By the conclusion, much of the city is reduced to a flattened, blaze-heavy hellscape.

(Those images share an eerie similarity with some of the horrific scenes from the recent destructive wildfires that swept through Pacific Palisades, Malibu and Altadena in January.)

Los Angeles also winds up in harm’s way in “San Andreas” (2015), starring Dwayne Johnson as a top search-and-rescue helicopter pilot with the Los Angeles Fire Department. The movie, with its impressive visual effects, depicts an eruption along the San Andreas fault line that wreaks havoc along the West Coast, endangering Los Angeles and San Francisco.

To be sure, Los Angeles is not the only location to be reduced to rubble by Hollywood filmmakers. Paris was felled by a massive meteor in “Armageddon.” “Twister” and its sequel “Twisters” laid waste to vast regions of Oklahoma. “Escape from L.A.” is the sequel to Carpenter’s far more accomplished “Escape From New York,” which has similar themes.

Still, “Los Angeles Plays Itself” narrator Encke King says that “the entire world seems to be rooting for Los Angeles to slide into the Pacific or to be swallowed up by the San Andreas fault.”

The documentary highlights a sequence in 1996’s “Independence Day” in which a group of revelers go to the top of the First Interstate World Center, now known as the U.S. Bank Tower, to greet the hovering spaceship above it, thinking the aliens inside are friendly. They gaze in wonder as the bottom of the ship opens up, revealing a warm blue light. Seconds later, a giant ray appears, shattering the tower and the celebratory mob.

“Who can identify with a caricatured mob dancing in idiot ecstasy to greet the extraterrestrials?,” King asks, once again summoning the spirit of Davis. “There’s a certain undertone of ‘good riddance’ when kooks like these are vaporized by the earth’s latest ill-mannered guests.”

The famed Hollywood sign is history in the wake of a devastating series of tornadoes in “The Day After Tomorrow.”

(Twentieth Century Fox)

Brad Peyton, director of “San Andreas,” says the lure of these disaster films is largely driven by the city’s landmarks: “There are all these landmarks that are easily recognizable all over the world. It’s a big target for filmmakers like me who are making movies for the world to see.”

Paul Malcolm, senior public programmer at the UCLA Film & Television Archive, has a different take: “Los Angeles is a city of constant change — it reinvents itself, tearing down old buildings and putting up new ones. Hollywood is also in constant flux and turmoil. Maybe Hollywood is processing its own anxieties about change and inflicting upon its hometown.”

In addition to the scenes that highlight spectacle and moments of heroism, some filmmakers also include more serious issues about disaster preparedness and structural shortfalls. Peyton, who is from Canada, remembers being in an underground garage somewhere in Los Angeles and thinking “this would be the worst places to be stuck if an earthquake ever hit. That thought lodged in my mind for years.”

In “Volcano,” an underground volcano erupts under MacArthur Park, sending rivers of lava through the subway system and spilling out from the La Brea Tar Pits onto Wilshire Boulevard’s Museum Row. Seismologist Amy Barnes (Anne Heche) suspects that a volcano may have been activated after an earthquake. She criticizes local officials who approved an underground subway, saying: “The city is finally paying for its arrogance, building a subway under land that is seismically active.”

Author and filmmaker Craig Detweiler (“Remand”) said the popularity of the “wreck L.A.” films could also be inspired by envy: “For audiences who hate California, there’s a certain schadenfreude in seeing it destroyed because of this jealousy of our wealth as well as our weather.”

The popularity of such fare once inspired its own subgenre — “Los Angeles Destroys Itself” — curated by the UCLA Film & Television Archive for the Los Angeles Film Festival.

The slate included 1988’s “Miracle Mile,” where the intersection of Fairfax Avenue and Wilshire Boulevard becomes the center of a riot, filled with residents terrified by reports of incoming nuclear missiles.

In “Volcano,” with Tommy Lee Jones and Anne Heche, an underground volcano erupts under MacArthur Park, sending rivers of lava through the subway system and spilling out from the La Brea Tar Pits onto Wilshire Boulevard’s Museum Row.

(Lorey Sebastian / 20th Century Fox)

Greg Strause, who directed “Skyline” and founded a special-effects company with his brother Colin, agrees that viewers take guilty pleasure in seeing Los Angeles landmarks ripped to shreds. “Anytime you see a landmark getting flipped on its head, that will get people off their couch and into movie theaters,” Strause said.

“Skyline” stars Eric Balfour and Scottie Thompson as Jarrod and Elaine, a Brooklyn couple who travel to Los Angeles to help Jarrod’s friend, wealthy entrepreneur Terry (Donald Faison), celebrate his birthday. When aliens launch an attack, all of them become trapped at Terry’s Marina del Rey penthouse.

At one point during a break in the attack, a distressed Elaine, who is pregnant, says quietly, “I hate L.A.”

“Skyline” was released in 2010, and even though Hollywood has not set its sights on destroying Los Angeles in the last few years, UCLA’s Malcolm would not be surprised if they made a resurgence: “There will always be an audience for those films, where we can experience safely what we always dread.”

Content shared from www.latimes.com.