There have been a number of close calls throughout sports history. Think of how if one play, one decision, one moment was slightly changed, everything might be different. What if Ray Allen didn’t make that three in Game 6 of the 2013 NBA Finals? What if Alex Gordon tried for an inside-the-park home run to tie Game 7 of last year’s World Series? What if the Seahawks ran the ball from the one-yard line instead of trying to pass it?

We can always debate the great what-ifs throughout sports, but there’s one tragedy that happened a century ago, which quite possibly could have changed the entire sports landscape as we know it.

It’s the story of how the NFL was created, thanks in part to a man oversleeping.

Getty Images

SS Eastland Disaster

This year marks the 110th anniversary of the SS Eastland Disaster. The SS Eastland was a passenger vessel that was primarily used for tours. On the morning of July 24, 1915, Eastland and three other ships were taking employees from Western Electric Company’s Hawthorne Works in Cicero, Illinois, to a picnic in Michigan City, Indiana. Since a lot of the workers were unable to afford vacations or take time off, this was a very big event in their lives.

Unfortunately, the SS Eastland was not the most structurally sound vessel. Because of the Titanic disaster three years earlier, vessels were retrofitted to include additional lifeboats should another sinking occur. This added even more weight to the Eastland and made it quite top-heavy.

Docked in the Chicago River, the ship reached its capacity of 2,572 people. It started listing towards the port side, away from the wharf, and within 20 minutes, it had completely tipped over onto its side, coming to rest at the bottom of the river. Though the water was only 20 feet deep, a number of passengers had already situated themselves below deck and were trapped inside or crushed by heavy items. In total, 844 passengers and four crew members died – the biggest maritime tragedy that’s ever happened on the Great Lakes.

(public domain)

One of the people who had a ticket for that boat? A guy named George Halas. At the time, the 20-year-old George Halas was a temporary worker for Western Electric.

There are a number of differing reports as to why George missed the boat that day. Some suggest that Halas’s brother Frank was helping George get in shape to play football at the University of Illinois and wanted to weigh him before he left. Another theory is that he was attending the picnic to play in the company softball game, and since the game was scheduled for later in the afternoon, he was going to take another boat that wasn’t leaving so early.

The final theory comes from Charles Brizzolara, the son of Halas’ longtime business partner Ralph Brizzolara, who suggests that Halas simply overslept. It’s interesting to think an alarm clock (or lack thereof) may have saved Halas’ life.

Whatever the reason, Ralph Brizzolara and his brother waited for Halas, but when he didn’t show, they boarded the ship and went below deck. Things looked bleak when the vessel capsized, but an unknown person pulled both Brizzolara and his brother out through a port window. They never found out who rescued them, but Brizzolara remained a business partner with Halas throughout the rest of their lives.

In fact, Halas was listed among the casualties of the ship in the newspaper. When two of his fraternity brothers showed up at his house to offer their condolences, Halas shocked them by opening the door himself. The close call offered him a new outlook on life, and in 1920, he took a position with the A.E. Staley Company, a starch manufacturer. The company sponsored a football team called the Decatur Staleys. Despite one successful season on the field, a poor financial situation resulted in Halas getting full control of the team.

In 1920, George Halas attended a meeting in Canton, Ohio, with representatives from other independent professional football teams. In a meeting that took place at Ralph Hay’s Hupmobile showroom, George and other pioneering owners like Ralph Hay, Jim Thorpe, and Joe Carr, Halas helped establish a football league which they named the “American Professional Football Association” (APFA).

Halas was instrumental in creating the league’s first constitution and by-laws, establishing standard rules for player contracts, and developing a league schedule. He also played a crucial role in implementing important policies that helped the league survive its early years, such as territorial rights for teams. In 1921, he moved the Staleys to Chicago. In 1922, he renamed the team the Bears. Also, in 1922, the league owners voted on a name change. The new name?

The National Football League

Previously, the NFL had been seen as a place where less talented and desired players went to compete. In 1925, George convinced Illinois star player Red Grange to join the Bears.

In the late 1930s, Halas and Clark Shaughnessy modernized the T-formation system, which was at its peak in the Bears’ 73-0 drubbing of the Washington Redskins in the 1940 NFL Championship Game – still the largest margin of victory in league history. Halas brought Hugh “Shorty” Ray into the NFL as a technical adviser. Ray, who had previously served as a Big Ten official, helped quicken the pace of the game, made the rulebook more compact and organized, and generally improved things for the offense in the NFL.

Halas also served in the Navy in both World Wars. After returning from World War II, he helped create an annual football game between the Army, Navy, and Air Force, with the Bears serving as hosts. The game ran from 1946-1957, and raised more than $2 million (about $25 million today) for relief agencies of the armed forces.

Other notable things Halas brought to Bears games – and, by extension, the NFL – include daily practice sessions, analyzing film of opponents, putting assistant coaches in the press box during games, placing a tarp on the field to protect it from rain, publishing a club newspaper, and broadcasting games by radio. Additionally, he offered to share the team’s television income with teams in smaller cities, as he felt that whatever was good for the league would also be helpful for the Bears.

George also played for the team (which went through iterations as the Hammond All-Stars and the Decatur Staleys) from 1919 until 1929 and served as coach of the team from 1920 until 1967, only taking a few years off during those years.

In his 40-year coaching career, Halas only had six losing seasons, and he won six championships and 324 games, an NFL record for nearly thirty years, and by far still a Bears franchise record. Halas was a charter member of the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1963.

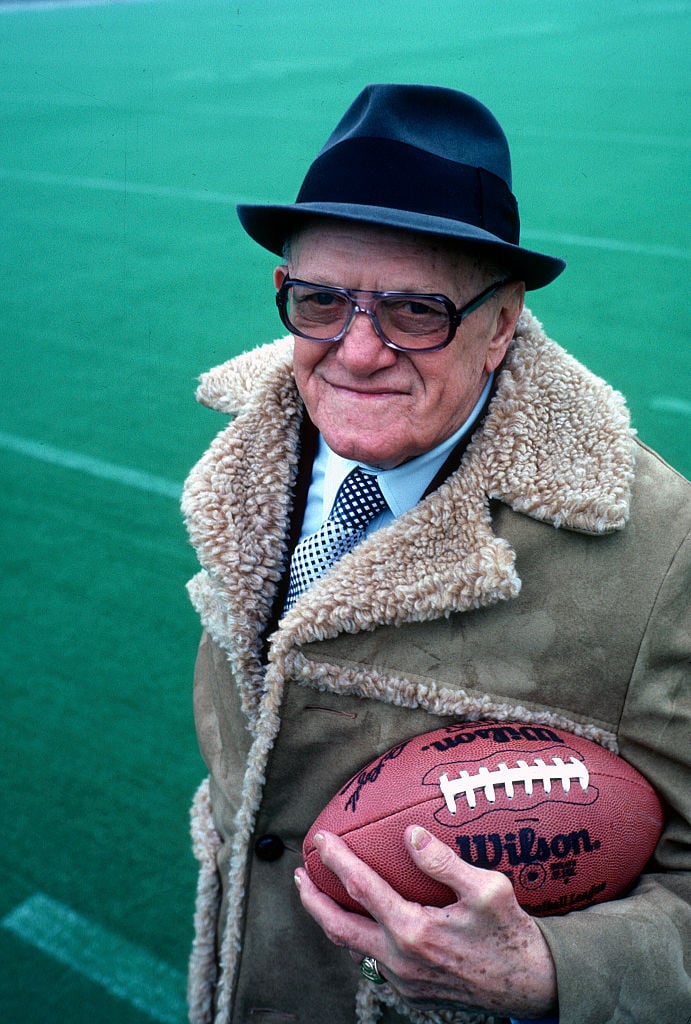

(Photo by Focus on Sport/Getty Images)

Chicago Bears Value

George died in 1983 at the age of 88. He was the last surviving participant in that iconic meeting in 1920 that gave birth to the NFL. He had two children, a daughter named Virginia and a son named George Jr., who unfortunately died in 1979. George Jr. had two children. Virginia had 11! According to George Sr.’s will, the team was inherited by Virginia and his 13 grandchildren, with Virginia owning 20% of the equity but maintaining 80% voting share.

Today, the Chicago Bears are worth $6.5 billion. Virginia Halas McCaskey died on February 6, 2025, at the age of 102. At the time of her death, she was worth $1.3 billion.

It’s interesting to think how the league would be different, or if it would even exist at all, if Halas had stepped aboard the SS Eastland that fateful morning of July 24, 1915. And perhaps even more incredible is that he very likely boarded the same boat years later!

After the ship was raised, it was turned into a gunboat and renamed the USS Wilmette by the Illinois Naval Reserve. It was then used as a training vessel at Great Lakes Naval Station, a place where Halas served during World War I. There’s a great chance he spent at least some of his time on the USS Wilmette.

Whether he knew he was riding the same ship from the tragedy, Halas was absolutely a pioneer in the game of football and provides a great example of how to make the most of an opportunity.