Academy Award-nominated actor James Earl Jones, who stuttered as a child, then burst forth to become one of America’s most recognized and articulate voices, has died.

Jones died Monday morning at his home in New York, his longtime agent Barry McPherson confirmed in a statement shared with The Times. A cause of death was not revealed. He was 93.

Jones, who was known for his rich, thunderous voice and commanding, almost forceful presence, had a decorated career that spanned decades and a multitude of roles — from King Lear to Darth Vader.

James Earl Jones, left, gets a hug from Mark Hamill backstage after Jones finished a performance in the Broadway hit “Fences” in 1987 in New York. Both actors worked together in the “Star Wars” films — Hamill in the role of Luke Skywalker and Jones as the voice of Darth Vader.

(Frankie Ziths / Associated Press)

Jones said it was the painful experience of being a stutterer that made him appreciate speech with such passion.

“The desire to speak builds and builds until it becomes part of your life force,” Jones recalled in his biography, writing of the years of childhood silence preceding his stage and film career.

“If I hadn’t been a stutterer,” Jones told the Los Angeles Times in 2014, “I would never have been an actor.”

Critics were fascinated by Jones’ booming, resonant voice. They called him thunder in a bottle; they compared him to civil rights activist Paul Robeson — and Paul Bunyan. Jones’ voice was “pitched in the key of heroism,” wrote Washington Post critic Peter Marks.

Some mistakenly called him a baritone. He wasn’t. He was a rare, natural bass — a lucky birthright, he said.

To that genetic good fortune, Jones added acting prowess. He was distinguished by the “elemental force he brings to the stage,” Marks wrote. He performed Tony-winning Broadway turns, an Oscar-nominated film role, camp movies and prime-time television dramas.

He was Othello, Hamlet and Lear. He did commercials and, of course, voice roles — so many he lost track. “This … is CNN,” he boomed. In public, he was more often recognized for his voice than his face.

Long after childhood, he still battled the stutter. He remained transfixed by the challenge of emotional expression, which he called a deep human need.

“The farther you get into language and articulation, the father you get from emotion. You have to get back into song and poetry,” he told The Times in 2002.

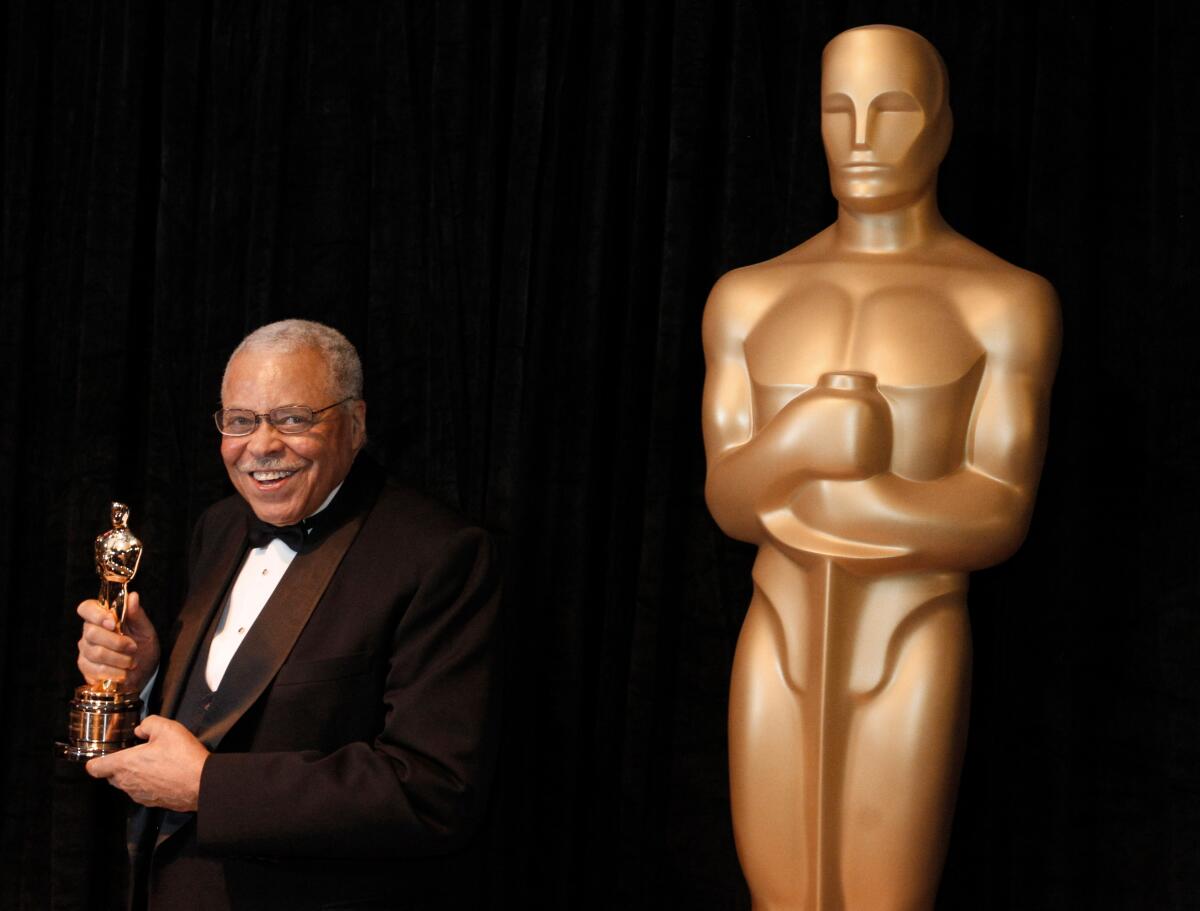

James Earl Jones was awarded an honorary Oscar at the 84th Academy Awards in February 2012.

(Chris Carlson / Associated Press)

James Earl Jones was born Jan. 17, 1931, in Arkabutla, Miss., the son of boxer and actor Robert Earl Jones and Ruth Williams, a tailor. He was raised by his grandparents Maggie and John Henry Connolly; his father left home before he was born. His mother, whom he later suggested had mental health problems, was often away. As he reached school age, he and his family moved to Michigan.

At age 12, Jones began to stutter. In his distress, he fell silent and scribbled notes in lieu of speaking. His self-esteem eroded, and in school he became a nearly anonymous figure.

But a high school teacher discovered he wrote poetry in secret, Jones recounted in his 1993 biography “Voices and Silences,” written with Penelope Niven. “If you like words that much, James, you ought to be able to say them out loud,” the teacher told him.

The teacher did more than encourage Jones. He researched stutterers and learned that some were helped by reading aloud.

At last, the teacher persuaded Jones to try this technique. Jones’ life pivoted on what came next: He found he was able to read before the class without a stutter. The teacher then handed him a volume of Shakespeare and told him to read aloud for practice, Jones said.

Years later — long after he had become a famous actor and household name — Jones continued to mention the teacher in interviews, finally crediting by name — first and last — Donald Crouch.

Jones won a scholarship to the University of Michigan and earned a baccalaureate theater degree in 1955 (16 years later, he was also awarded an honorary degree from the school). He served two years in the Army and then went to New York, where he met his father for the first time.

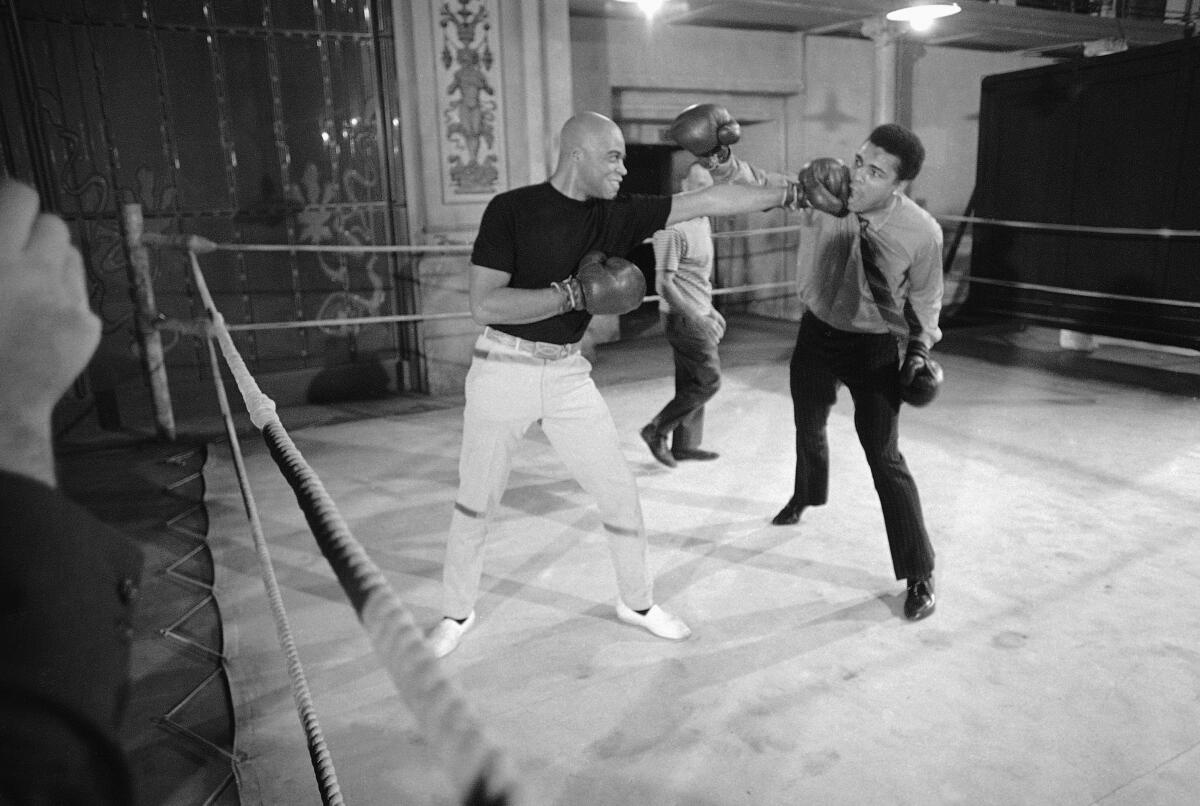

Ever one to go along with a gag, Muhammad Ali, right, allows himself to be tagged with a left thrown by actor James Earl Jones, star of the Broadway hit, “The Great White Hope,” in a publicity photo in Hollywood in 1969.

(GB / Associated Press)

The pair struggled by, polishing floors and cleaning theaters. Finally, Jones got his first off-Broadway role, holding a spear in Shakespeare’s “Henry V.”

Jones was a strapping, green-eyed man whose emotive face seemed always at the brink of laughter or fury. He was a natural stage presence. He joined an ensemble cast with Cicely Tyson in the off-Broadway production of Jean Genet’s “The Blacks” in 1961. With the New York Shakespeare Festival, he played Othello in 1963. Television spots and a soap opera role opened up, and he appeared in the film “Dr. Strangelove.”

He was cast as the lead in “The Great White Hope,” a Broadway play based on the life of boxing champion Jack Johnson. “Superb” is how critic Richard L. Coe summed Jones’ performance. He called Jones “physically convincing, vocally assured, consistently interesting.”

It was Jones’ breakout role: He won a Tony Award and was nominated for an Academy Award in 1970. He went on to win an Emmy, two additional Tony Awards, a Grammy for spoken word and, in 2011, a lifetime achievement award from the Motion Picture Academy, which cited his “legacy of consistent excellence and uncommon versatility.” He received Kennedy Center honors in 2002.

“People say that the voice of the president is the most easily recognized voice in America,” President George W. Bush said during the Kennedy ceremonies. “Well, I’m not going to make that claim in the presence of James Earl Jones.”

James Earl Jones and Cicely Tyson starred in “The Gin Game” in New York City in 2015.

(Walter McBride / WireImage)

His many film, television and stage credits over the next half a century included the plays “Fences” and “Paul Robeson,” the Emmy-winning lead in the short-lived “Gabriel’s Fire” and the movies “A Piece of the Action,” “Coming to America,” “Field of Dreams,” “Cry, the Beloved Country” and “Exorcist II: The Heretic.” He was the voice of King Mufasa in “The Lion King” and the narrator of “Scary Movie 4.”

Critics sometimes faulted his performances for pomposity. But especially in later years, Jones’ place was secure in the pantheon of renowned Shakespearean-trained film actors.

Even so, he never lost the habits of a struggling wannabe. He took every manner of job, seemingly no role too small or cheesy.

He announced awards shows, narrated documentaries and acted in commercials. He read audio books, pitched for Verizon. He later said his Darth Vader work had taken him little more than an hour, and he didn’t seem to think much of the role.

Some critics complained that he was wasting his considerable talent. How could a man who mastered the works of Anton Chekhov and August Wilson be content booming “Infidel defilers!” in “Conan the Barbarian”?

Jones insisted he was a character actor. But beyond this, he offered no ready answer. The best may have come from his second wife, Cecilia Hart, whom he married in 1982. (He divorced his first wife, Julienne Marie, in 1967.) Hart said Jones was simply a workaholic.

Whatever the reason, Jones continued a punishing schedule of stage acting into his 80s, even as he struggled with chronic pulmonary disease and was forced to use an oxygen tank between acts during performances. Yet he reunited with Tyson — reportedly 90 at the time — for the Broadway revival of “The Gin Game” in 2015.

Throughout his career, he played traditionally white roles as well as Black ones. He played the lead in a theatrical production of “On Golden Pond,” Big Daddy in “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof” and Lennie Small in “Of Mice and Men.”

Although his career spanned periods of intense political activity surrounding race, Jones carved his own path on race issues. He was proud of breaking ground as a Black actor. He talked of the historical degradation of Black people, but said one should not be defeated by it. He eschewed identity politics.

Craft came first. “You’ve got to play the culture, not the color,” he would say.

He spoke as a “language appreciator” whose thought still bore the mark of his silent childhood sufferings. He rejected claims of a separate Black cultural identity: Since Black Americans spoke English, they were basically European, Jones argued.

“Language is the only thing that defines culture,” he said.

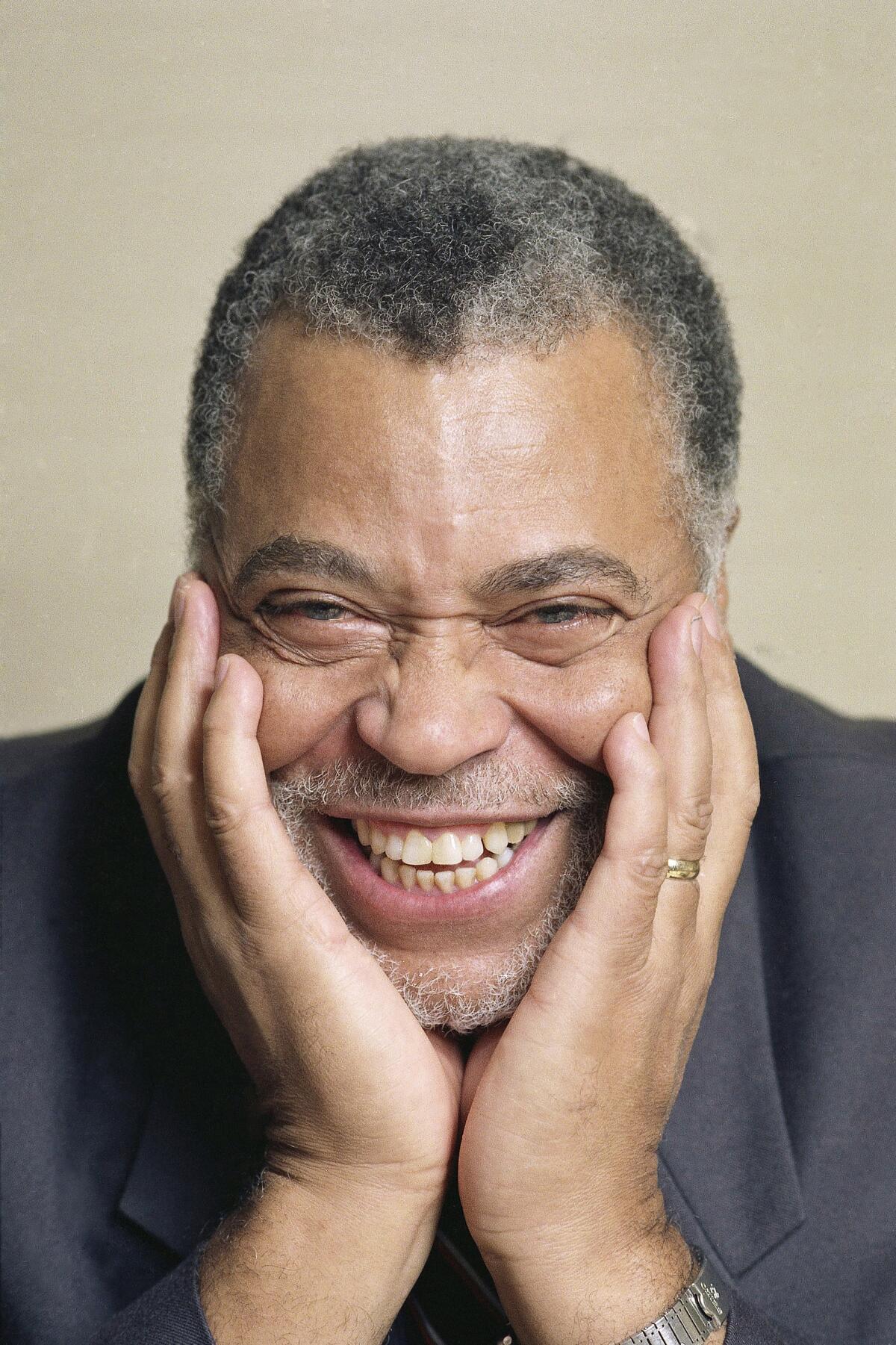

James Earl Jones, in 1990, around the time of the NBC movie “Last Flight Out” about the heroic efforts to evacuate 500 Vietnamese and Americans aboard the last civilian plane out of Saigon before its fall in April 1975.

(Bob Galbraith / Associated Press)

To the extent he mounted a racial crusade, it was through his acting — and specifically his hard-won mastery of spoken language.

“Anybody can carry a picket sign,” he told the Toronto Star in 2013, speaking in his trademark rumble. “But I think you should be able to articulate what that sign means.”

Jones’ wife died in 2016 after being diagnosed with ovarian cancer. He is survived by their son, Flynn Earl Jones , a voice actor.

Times staff writer Alexandra Del Rosario contributed to this report. Leovy is a former Times staff writer.