Today, it’s easier than ever to eat food from around the world. If a dish a good enough, it seems like it’s bound to find a market eventually and get eaten everywhere.

But that takes time, if it happens at all. When one type of food instead jumps the queue and becomes famous worldwide before any anything else, something a little more shady may be going on. Maybe we’ve all fallen victim to some government conspiracy. Luckily, it’s the delicious kind of conspiracy, which is one of the few types of conspiracies that work out great for everyone.

Pad Thai Was Invented by the Thai Government to Make You Come to Thailand

If you’ve never been to Thailand, have you ever wondered what they call Pad Thai over there? We refer to it as Thai food, but surely they don’t in Thailand itself, since they themselves are Thai. Canadians don’t call Canadian bacon “Canadian bacon.” The French don’t call French fries “French fries,” nor do they call them frites français. So, what do the Thai call Pad Thai?

Answer: They call it Pad Thai. This reveals the truth behind the dish — and behind the nation.

Pad Thai isn’t a traditional Thai dish but was commissioned as an invention at the end of the 1930s by Prime Minister Plaek Phibunsongkhram. The PM (who was called “Phibun” for short) wanted to create a national identity, and he figured that meant a national dish. Lots of people cooked their own kinds of noodles, both in his country and in the surrounding ones, so the team came up with this one standardized noodle dish, arbitrarily flavoring it with peanuts. Phibun named it “Pad Thai.”

He also named the nation, dubbing it “Thailand,” meaning “land of the free.” Before, it had been Siam. Pad Thai is as old as Thailand itself, if you say Thailand was founded in the 1938 with the Songsuradet Rebellion, but it’s otherwise misleading to call it a traditional part of Thai cuisine. Ritz crackers are older than Pad Thai.

So, that’s where Pad Thai came from. As for why it became so famous internationally, that’s its own little story. At the start of the 21st century, the Thai government launched a plan to fund thousands of Thai restaurants worldwide, and for them to use Pad Thai to introduce people to Thai culture. The plan worked. It’s why America has so many Thai restaurants right now, and barely any Cambodian restaurants, even though the two countries are right next to each other.

Mac and Cheese Was a Rationed Treat

You can probably name a dozen types of pasta and at least two ways to prepare each of them. Only one type of pasta, though, is such a casual food that it’s an appropriate side dish when you order barbecue. It’s macaroni and cheese, and it was one of the earliest Italian imports to America.

In 1793 — when some Italians in America were surely already eating macaroni — Thomas Jefferson had his own personal macaroni maker. He’d ordered it from Naples during his time in Paris. Other people in America ordered pasta imported from Sicily, and local pasta factories opened.

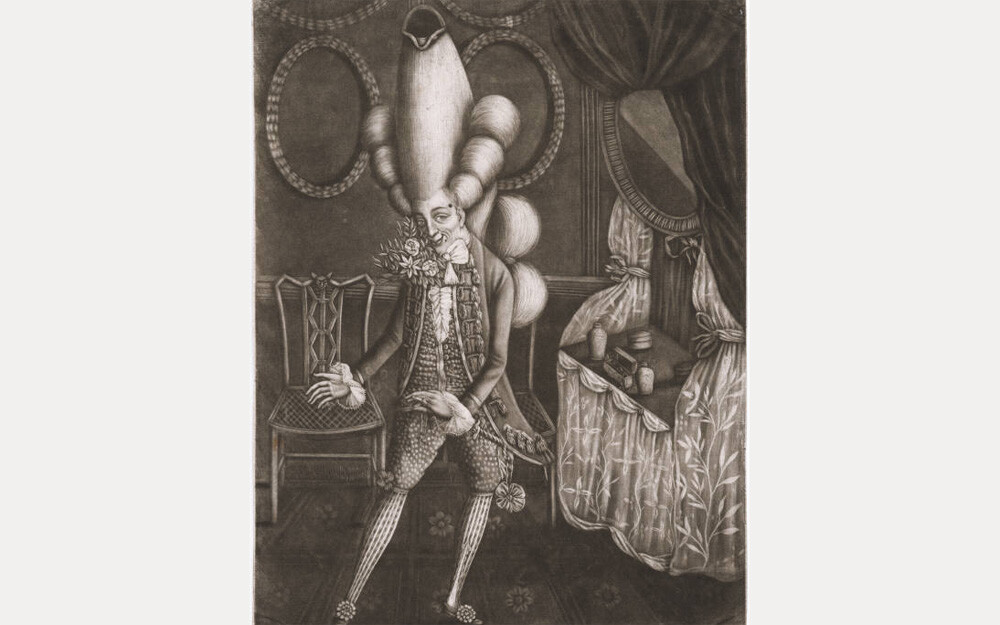

Around this same time, a song called “Yankee Doodle” namedropped macaroni, but that wasn’t directly related. The “macaroni” in that song was a type of effeminate man and his choice of hairstyle. That macaroni, in turn, got its name from men who’d toured Europe and visited Italy, and plenty of people at the time knew the macaroni slur but not the pasta.

That’s why mac and cheese became known in America. To know why it became super-popular in America, we need to fast-forward to the 20th century. This was when Kraft invented processed cheese and made packaged mac and cheese into a non-perishable cheap dish. Then came World War II, and Kraft got the government to assign Kraft Mac and Cheese the uniquely low price of half a ration point per box. People loaded up on this one affordable food, developed a taste for it and passed the tradition on to their kids.

Risotto, Meanwhile, Is Fascist

If we shift to pasta’s birthplace, at the same time that macaroni was getting really big in America, there was actually a push to kill pasta dead. Pasta caused “weakness, pessimism, inactivity, nostalgia and neutralism” in Italy, said a self-appointed food expert named Filippo Tommaso Marinetti. This baseless idea reached the ears of Benito Mussolini, who embraced it.

The country should wean itself off pasta, announced Mussolini. Instead, they should prepare dishes with rice. This way, men would become fit and quick again, and maybe they’d bring back the glory of Rome. His push for risotto didn’t succeed in eliminating pasta. But he did manage to make risotto popular, and it stuck around long after he was gone.

Mussolini likely never believed the pseudoscience behind pasta sapping people’s energy. He tried to switch to risotto because Italy grew its own rice but imported lots of the wheat it used to make pasta. That’s similar to why Phibun settled on Pad Thai for Siam’s new national dish. Before, lots of Thai people ate rice, which was imported, but he wanted to promote noodles made of wheat, which they grew domestically.

One Specific Policy Meant America Got Chinese Restaurants

During most of the 19th century, the U.S. had the world’s most open immigration policy. Anyone could show up and become a resident, which wasn’t the case in most other nations. That couldn’t have lasted forever, and the first limit on immigration targeted one specific group: Chinese laborers. The 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act blocked any laborers at all from migrating for a while, and also added a bunch of needless trouble for Chinese workers already here.

It carved out a few exceptions, however. Teachers could come from China, as could diplomats. Merchants could as well. In 1915, a court added restaurants to the list of businesses that counted as merchants, even though that’s not normally what “merchant” means. So, it was now possible to move from China to the United States — if you came to work at a Chinese restaurant.

An industry quickly opened up for shuttling people in from China, people who’d otherwise have no desire to work in restaurants. In a decade, the number of Chinese restaurants in America doubled. In another decade, it doubled again.

None of that would have worked, of course, if people didn’t like getting food from Chinese restaurants, but they did. Today, there are some 40,000 Chinese restaurants in America. “That’s more than the number of McDonald’s, Burger Kings and KFCs combined” is how one stat puts it. That’s quite a lot, considering just 1.5 percent of the population is ethnically Chinese. Though, perhaps not as impressive as there being 10,000 Thai restaurants in America, when just 0.1 percent of the population is ethnically Thai.

Follow Ryan Menezes on Twitter for more stuff no one should see.