Nowadays, Teen Titans’ rise can feel a bit inevitable. After all, it came on the heels of anime access in the U.S. moving from VHS tapes at your local comic or video stores to the mainstream. The Sci-Fi Channel’s Saturday Anime block introduced an entire generation to masterpieces like Akira, Ghost in the Shell, and Record of Lodoss War. Toonami and Adult Swim were airing various Gundam series, Sailor Moon, and Dragon Ball Z, as well as bringing new life to cult classics like Cowboy Bebop and Trigun. The biggest animated program in the country at the turn of the century was Pokémon, a full-on phenomenon seen as the biggest export in the history of Japan. Not only was anime more prevalent on American television than it had ever been before, its influence and style had begun steadily seeping into the cartoons being made in the good ol’ U.S. of A.

In 1993, Universal Cartoon Studios (now Universal Animation Studios) released the sci-fi action program Exosquad, which attempted to match the themes and elaborate storytelling seen in Gundam and Macross. By the late 1990s and into the early 2000s, elements of anime’s style began surfacing on series like Powerpuff Girls, Jackie Chan Adventures, and Samurai Jack. But it wasn’t until the arrival of Teen Titans on July 19, 2003, that an animated program created and developed in America truly attempted to mimic both the look and feel of anime, creating a true hybrid between the two animation styles.

Highly influenced by Marv Wolfman and George Pérez’s run on the New Teen Titans comics, the series followed the adventures of Robin, Beast Boy, Raven, Starfire, and Cyborg as they protect Jump City from various supervillains and interdimensional beings, all while enduring and overcoming the difficulties of teenage life. The series was a complete outlier compared to the DC Comics animated programs audiences had been accustomed to. It was not only a major hit for Cartoon Network — one that gave birth to a franchise that still goes on to this day — it also paved the way for American animation studios and creators to develop programs that would feature a heavy anime influence.

Image: Warner Media

Image: Warner Media

Image: Warner Media

Image: Warner Media

Teen Titans could have easily been made in the mold of Justice League and the many DC animated series that had come before it. However, the individuals who brought the teenage supergroup to TV for the first time decided that it was best if this new series went in an entirely new direction, even if they didn’t know just how different it would end up becoming. Development on the series started on Sam Register’s first day as senior vice president of original animation at Cartoon Network. “I was a huge fan of the Wolfman/Pérez Titans, and when my job was moved to development, the first thing I wanted to do — before I did anything in my new development role — was to see if Teen Titans was available,” Register said in Pacesetter: The George Perez Magazine. He called and later met now former DC Comics president Paul Levitz at the old DC Comics headquarters in New York City, who gave him the green light.

At the time, Cartoon Network was the premier destination for action cartoons, thanks to Samurai Jack, the many anime titles featured on both Toonami and Adult Swim, and Justice League — programs that were more mature (and violent) than anything showing on Nickelodeon or the Disney Channel. Register understood that those programs were successful with both critics and the network’s teenage audience, but he felt that the channel was neglecting a key demographic with its focus on mature cartoons: younger kids between the ages of 6 and 11. Teen Titans would serve as the action series for the middle school crowd. “The 6- and 7- and 8-year-olds were not gelling with the Justice League and some of the more fanboy shows,” Register told CBR. “The main mission was making a good superhero show for kids.”

To achieve this, Register strongly believed that the series had to both feel and look different than the other DC series before it, which meant breaking away from the more naturalistic and angular house style developed by Bruce Timm in the 1990s with Batman: The Animated Series. After a number of attempts failed to deliver what Register had in mind, the series was passed off to the person who would end up delivering what the executive asked for and then some: Emmy and Annie Award-winning producer Glen Murakami.

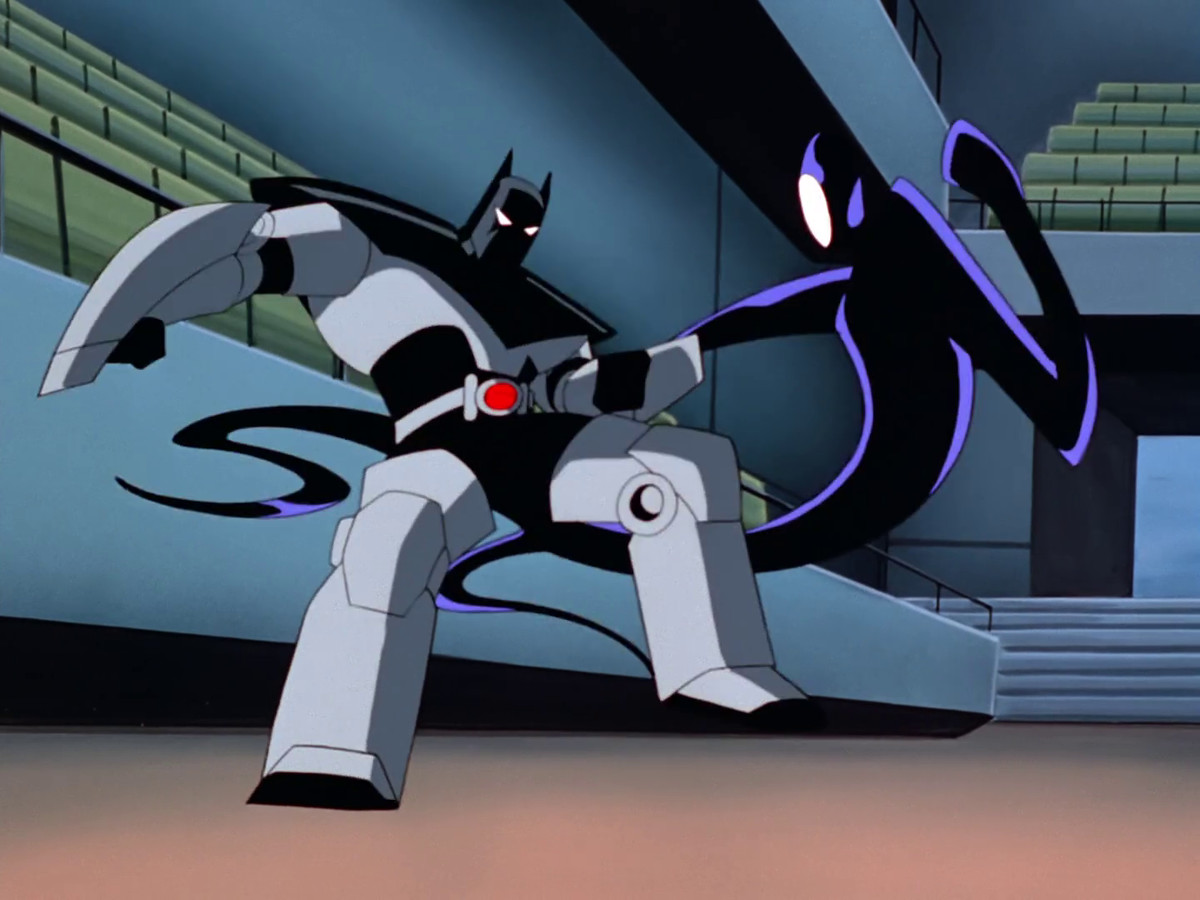

Stumbling into the animation industry in the early 1990s thanks to a recommendation by Keith Weesner (a friend who worked as a background artist on B:TAS), Murakami started as a character designer for the iconic 1992 series, spending the rest of the decade working his way up to art director on The New Batman/Superman Adventures and then to becoming a producer on Batman Beyond. It was there where he would first begin using elements of Japanese and anime culture, such as the use of Japanese typography in the show’s intro, and the transformation of Gotham from a noirish sprawl to a cyberpunk metropolis resembling Akira’s Neo-Tokyo and Ghost in the Shell’s New Port City.

Image: Warner Bros. Animation

Image: Warner Media

Both the executive and the producer decided early on that the roster for the show would match the one seen during Wolfman and Pérez’s run, sans Kid Flash (who does appear in season 5) and Wonder Girl (who cameos in two episodes). The Amazon and the speedster were then under different licenses, and both Register and Murakami wanted this series to focus on fresh faces that younger fans were not familiar with. Like Register, Murakami was also a fan of New Teen Titans during his youth, so he jumped at the chance to put his own take on the characters. He took inspiration from his many years working under Timm and the programs he used to watch on UHF channels growing up: the works of Shotaro Ishinomori (Super Sentai, Android Kikaider, Cyborg 009), Gatchaman, and many of the anime titles showing on the network, particularly FLCL.

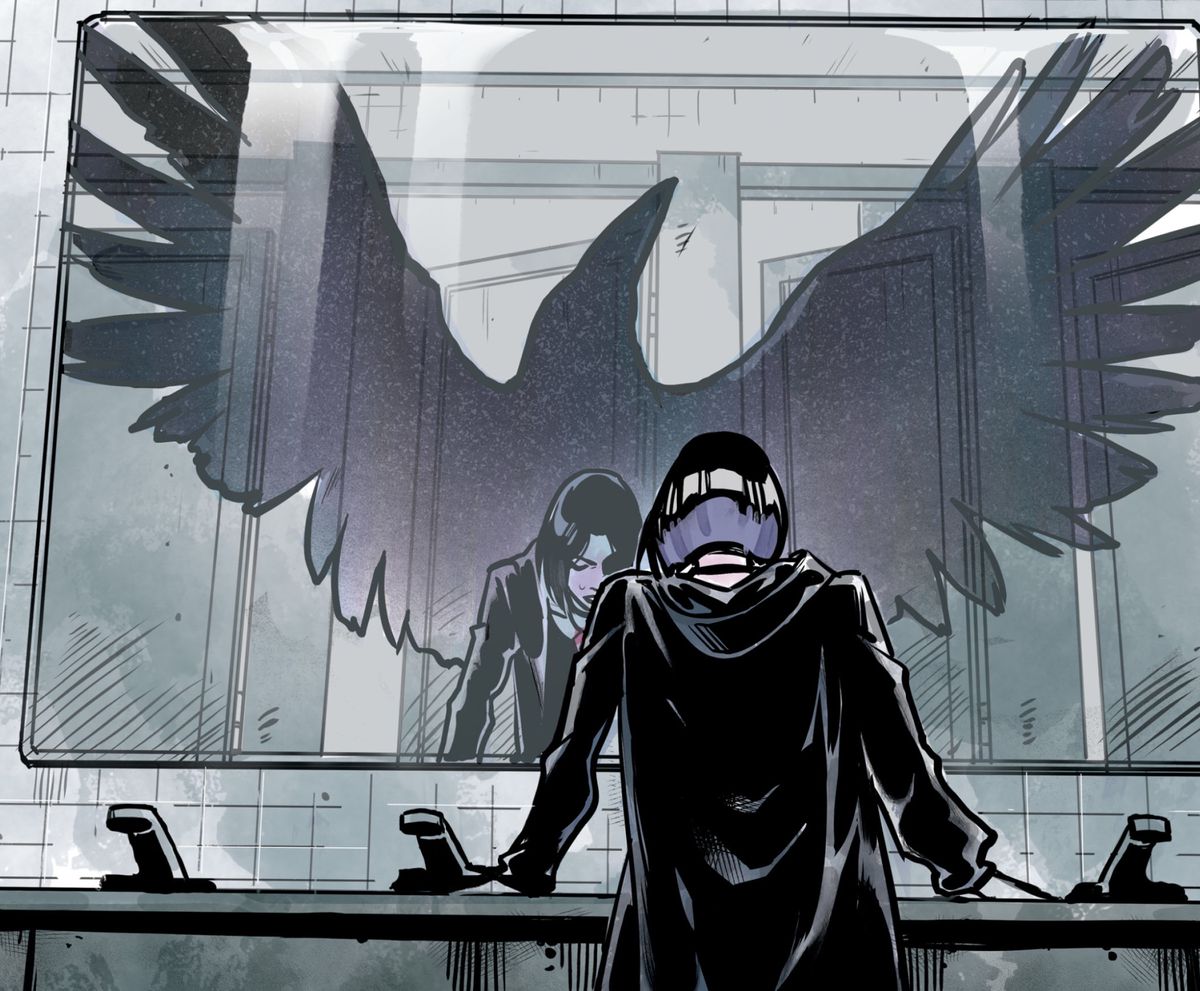

Murakami’s designs still held on to the minimalist look associated with the ’90s/2000s DC series, but now carried a strong infusion of anime style. Each of the main characters (except Cyborg) was given the kind of large, expressive eyes associated with anime style. Beast Boy and Robin were given spiky hairdos, with the Boy Wonder’s design featuring a lighter streak in the middle, having him more closely resemble characters in YuYu Hakusho than anything in the DC Animated Universe. Female characters like the villain Jinx and Raven went from having blond and black hair to the more anime-inflected pink and purple. And Cyborg was given light blue, Kikaider-style panels that show off some of the circuitry that powers the young man. “I wanted to be completely surprised,” Register told Cinescape Magazine. “I wanted something that kind of popped. And that anime style was going to do that.” The executive loved it so much that he even came up with his own term for it: “Murakanime.”

As Murakami and his staff began shaping what would become the first season of the show, both the writing and the art staff began leaning further into using elements of anime’s style, experimenting with speed lines (which were already being used in Western cartoons) and super-deformed takes, moments where characters’ faces or bodies morph to accentuate both their positive and negative feelings.

To Murakami, a merging of American and Japanese styles of animation was inevitable, as anime was becoming more a part of what younger people (and those in the industry) were seeing on television. “Today’s generation is growing up with Pokémon and all the shows now available on Cartoon Network,” Murakami told Animation World Network. “I had seen a lot of different things being done with anime, and I thought that was a wonderful opportunity to tell stories in a different way, a very stylistic way. So it just seemed sort of natural that a hybrid would occur.” The question that remained on Murakami’s mind and that of his staff was whether all this experimenting would actually work.

“We asked ourselves, ‘Could we pull it off?’” Murakami told the fan site Titans Tower. “We weren’t sure whether this stuff would look good once it got animated overseas.” This was the first time something like this had ever been attempted; if Register and Murakami misjudged the direction they decided to go with Teen Titans, the series could have ended up an anachronistic mess whose visuals would act as a disservice to the medium it was so influenced by. Thankfully, any concerns held by Murakami and his team were quickly dissipated once they got to see their work in motion. Now confident they made the right choice with the visuals, they further experimented, escalating the use of super-deformed expressions and reactions seen more in anime comedies than your average superhero series. That confidence would be justified as soon as viewers got their first look at “Murakanime” for themselves.

Teen Titans’ visual style, its combination of action and comedy, and its focus on character based stories made it distinct among CN’s action lineup, and ultimately a staple of the Cartoon Network through the 2000s. It was a series that younger audiences who perhaps were not moved by Justice League or The Big O could appreciate, but there was also enough drama and emotion for older kids to latch onto. The series featured episodes that had a darker tone and tackled serious issues that teenagers of all generations go through — things like body issues (Cyborg), learning how to control intense emotions (Raven), fitting into a brand new-environment (Starfire), understanding that you don’t have to go through obstacles alone (Robin), and first love and heartbreak (Beast Boy).

The series earned praise for its visual presentation, its unique take on superhero stories, and the staff’s adaptation of two of the most important storylines in New Teen Titans, “The Judas Contract” and “The Terror of Trigon.” Sanded down considerably for its younger audience (so no intimate relations, torture, or deaths), it’s where the drama that made the comics series one of the top titles of the 1980s was propelled just enough to stand out among the battles with the likes of Control Freak and Mad Mod, while also keeping it within the parameters of children’s TV. Those two story arcs, along with other serious episodes like “Masks” and “Haunted,” are some of the darkest yet most engaging episodes the series had to offer. And, of course, there was its classic theme song.

Register had first seen Puffy (renamed Puffy AmiYumi in the States for legal reasons) in 1999, when he happened to catch one of their music videos on a New York public access channel. He didn’t understand a word, but found himself intrigued by what he was watching. He waited until the credits for the video came up, only to see that they were in Japanese. Three years later, in his new, more prominent role at the network, he was stuck in LA traffic and while listening to the radio, he happened to hear the exact same tune. Register listened intently for anything that could tell him who the group was, and once he heard the words “Puffy” and “Sony” come out of his speaker, he began making plans to call the label to discuss bringing the duo to Cartoon Network.

During their first meeting for what would become Hi Hi Puffy AmiYumi — the first Cartoon Network show to feature live-action segments and one of the few aimed at young girls — Register asked if they would be up to perform the theme song for Teen Titans, well aware of the direction Murakami and his team were taking the series. The duo agreed and their producer, Andy Sturmer of the band Jellyfish (which counted Murakami as a fan), penned the lyrics. “The girls performed it and everyone was singing the song. It was like a micro pilot for the show,” Register said to License Global. The Teen Titans theme (which the group also performed in Japanese) not only gave us one of the catchiest cartoon themes of the 2000s, it further connected the series with its influence. Japanese labels have licensed music for anime openings since the 1970s, but Teen Titans marked the first time a Japanese group performed the theme song for a Western cartoon. Register credits the theme song as a reason Hi Hi Puffy AmiYumi got greenlit.

The series was nominated for three Annie Awards and a Motion Picture Sound Editors award throughout its run. Its success on television made an immediate impact in the comics, as Raven’s and Beast Boy’s costumes — as well as Cyborg’s armor design — were modified to more closely resemble their animated counterparts. Starfire’s appearance would stay as it was for a while, but in 2015, artist Emanuela Lupacchino provided a redesign of the character for her stand-alone title that calls back to Murakami’s version.

Characters created for the series, such as Más y Menos, the Guatemalan twin heroes who can move at incredible speed only when they touch, along with villains Cinderblock and Red X, were later incorporated into DC Comics continuity. Register himself wound up seeing his name in the title he grew up reading, as his name was given to the alter ego of Zookeeper, a new villain created by comic writers Geoff Johns and Tom Grummett. The series’ influence on its source material was quick, but nothing compared to what it would do for how cartoons would look in the coming years.

In the years following the premiere of Teen Titans, a number of anime-influenced Western animated programs began appearing on Cartoon Network and its competitors. Disney’s Jetix had Super Robot Monkey Team Hyperforce Go!, an action-comedy series that was highly inspired by Super Sentai and Voltron (and created by former Teen Titans writer Ciro Nieli) in 2004. A year later, Cartoon Network released Ben 10 and the Murakami-produced The Batman, a controversial take (at the time) on the caped crusader as he, along with his iconic rogues’ gallery, were given anime-inspired redesigns and even fighting styles. That same year also saw the release of Nickelodeon’s Avatar: The Last Airbender, one of the most highly acclaimed animated titles of the decade. It would become the series (along with its sequel, The Legend of Korra) that fans point to as the most clear example of anime-inspired Western animation, even though it appeared two years after Teen Titans.

Teen Titans would run for 65 episodes over five seasons, ending in 2006. During early production of the fifth season — with a sixth one planned and as anime-influenced Western animation was on the rise — the channel informed the staff that the show was coming to an end. A Justice League Unlimited-style rebrand, which would feature teenage superheroes from across the world, was rejected, leaving the made-for-TV movie, 2006’s Trouble in Tokyo, to serve as the series finale.

There has never been a concrete reason given as to why the series was canceled. David Slack, head writer for seasons 1-4, tweeted in 2017 that he had heard various reasons as to why CN pulled the plug. One was that ratings had dipped in the fourth season, which focused on the Terror of Trigon arc; the other was that Mattel, which had recently struck a deal with CN to produce figures for all of its original programming, wanted it gone because Bandai held the Teen Titans license. While the series would live on in reruns on both Cartoon Network and its sister network Boomerang, it would not be until 2013 that CN aired new Teen Titans episodes — albeit in a fashion that no one could have expected.

Seven years after the first airing of its final episode, “Things Change,” the series was rebooted with Teen Titans Go!, an even more comedic and lighthearted series aimed at elementary school kids (Murakami is involved as a producer). Still running after eight seasons (and with all members of the original cast), Go! would, on occasion, make callbacks to the 2003 series, with the original animated Titans appearing briefly during the credits of 2018’s Teen Titans Go! To the Movies. The two versions would later meet in the straight-to-video Teen Titans Go! vs. Teen Titans, where they would face off and then later team up alongside a collection of other Titans teams throughout different dimensions, as they attempt to stop Trigon from destroying the multiverse.

While it would go through a lull in the late 2000s to early 2010s thanks to networks altering their programming choices, the last decade has seen a number of Western programs with a strong anime aesthetic. Series like Korra, Disney’s Star vs. the Forces of Evil, the work of Texas-based Powerhouse Animation Studios (Castlevania, Seis Manos), Netflix’s reboot of She-Ra and The Princesses of Power, Cartoon Network’s Steven Universe, and the latest series from Adult Swim, My Adventures With Superman. The first program centered around The Metropolis Marvel since 1996’s Superman: The Animated Series, this latest attempt to remake the Superman mythos for the modern age is very in the vein of Teen Titans. From Dou Hong’s character designs to its color scheme to even its intro, the series is highly influenced by anime, particularly the top shonen and shoujo titles of the 1990s and 2000s.

Currently, anime is considered a global power that rivals Hollywood entertainment due to the emergence of streaming, with services all competing for the growing and loyal anime fan base. The medium has come a long way since the days of tape trading and cable TV blocks, and the same could be said for the style of Western animation it has influenced. No longer would a series like Teen Titans be viewed as an outlier or the product of a trend; anime-influenced animation is as common today as cartoons featuring kids with special powers and talking animals. For the adaptation of his favorite comic book, Register wanted something different, something iconic. Murakami and his team accomplished that and more. Ultimately Teen Titans was not just a good superhero show with a unique style and a catchy theme song — it proceeded to bring about the inevitable.

All five seasons of Teen Titans are streaming on Max.