Listen to this episode of Binge Sesh

There may be no figure in Lakers history more misunderstood than Kareem Abdul-Jabbar. And “Winning Time” tries to correct, or at least complicate, the record.

In Episode 5 of “Binge Sesh,” hosts Matt Brennan and Kareem Maddox discuss the perception and reality of the NBA’s all-time leading point scorer. With insights from an array of special guests — including Solomon Hughes, who plays the Lakers legend in HBO’s drama series — we look back over Abdul-Jabbar’s career as a star center and civil rights activist to answer the question: Has he been unfairly excluded from the conversation about basketball’s greatest-ever player?

Catch up on Episode 4: Does ‘Winning Time’ get Claire Rothman and Jeanie Buss right?

Robert Wade: I went to a party at UCLA, would have been 1966. And it was predominantly Black people.

Kareem Maddox: That’s my Uncle Robert. He grew up in L.A. in the 1950s and 1960s.

Wade: And it was early in the party before the real music and dancing part started. And the woman who was hosting the party, uh, yells out, “Can somebody turn on the light?” And I see what looks like an arm reach from the opposite side of the room — 10, 12, 15 feet, it looked like — and hit the light switch.

It stands out as a memory because, man, the guy was long. I’d never seen anybody with a reach like that before. And it was Lew Alcindor.

Maddox: I just love this image of a literal wallflower, like someone who’s trying to blend in but can’t help but to stand out. Because we’re of course talking about the man who would become Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, the NBA’s all-time leader in points scored, a six-time NBA champion, the Finals MVP twice, the league MVP six times, and a 19-time All Star.

Matt Brennan: That is a wild list of accomplishments.

Maddox: Yeah. And he did it because he was the king of the sky hook, and he played in the league for a solid two decades, which is unheard of. But when people are talking about who’s the NBA’s greatest player of all time, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar actually doesn’t come up all that much. This week on “Binge Sesh,” we’re going to try to figure out why.

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar shoots a sky hook over Clippers player Benoit Benjamin during a November 1987 game at the Forum.

(Los Angeles Times)

::

Maddox: Welcome to “Binge Sesh.” This season, we’re diving into the stories behind HBO’s “Winning Time,” the saga of the Showtime-era L.A. Lakers. I’m Kareem Maddox, professional basketball player — and kinda named after Kareem Abdul-Jabbar.

Brennan: And I’m Matt Brennan, TV editor of the Los Angeles Times. I’m named after the Catholic saint, I guess.

Maddox: St. Matthew. One of my favorites. So, Matt, if you had to sum up the public line on Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, what would you say?

Brennan: I think it depends on how charitable the person that you’re asking is. I think a charitable person would say that he was aloof. Above the fray. Cold. Not interested in engaging with the fans.

I think less charitable people would have described him as an a—.

Maddox: Your sentiment actually is summed up by Los Angeles Times columnist Bill Plaschke.

Bill Plaschke: Kareem Abdul-Jabbar is the greatest least loved player in Laker history. He’s just so distant. So hard to embrace. It is sad, sad to me. He’s gotten more affectionate as the years have gone on, but you can just tell at Laker games, when someone, one of the former Lakers, walks into the house, what the cheers are like. They see James Worthy, they go crazy. They see Coop, they go crazy. They see Magic, they go crazy. They see Kareem, ehhhhh. It’s really sad. And that’s the narrative that has been written for him.

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and Larry Bird exchange angry words after some rough play in 1984’s NBA championship series.

(Los Angeles Times)

He’s brilliant. Think about it. He’s, statistic-wise, he’s the best Laker ever. Yet would somebody even say he’s a top five Laker of all time? I don’t know, because of his popularity. That’s how I think he’ll be remembered here: as kind of aloof, brilliant, bold, strong and very unembraceable.

Brennan: It’s interesting because the conversations that we’ve had with people that we’ve interviewed for the podcast have tended to focus on the outside perception of Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, and I think maybe what we’re trying to add in this episode is a little bit more of, like, “What would Kareem say?”

A lot of the discomfort he felt wasn’t just not being comfortable with being famous — although that may be the case — but being uncomfortable, having to walk this line between being this star NBA player and being someone who had real and legitimate objections to the way that American domestic and foreign policy was going and the way that most professional sports tried to skirt or avoid that. Kareem would be more in the category of Muhammad Ali or, say, Spencer Haywood, who stood up to the NBA in order to get drafted straight out of high school.

Brennan: Rachel Laws Myers, the author of “Race and Sports” and an expert in this subject, talked to us about this.

Rachel Laws Myers: He was too political. When you think about sort of this pre-Kareem or like Kareem as sort of the measure bar, you see a lot more athletes that had this kind of solidarity and knowledge of, of those who came before them, you know, whether it was, you know, Wilma Rudolph and Jesse Owens and Muhammad Ali and the fight and the fight and the fight.

Brennan: So how do you find someone who can shine a light on one of the most elusive, misunderstood and righteous figures in NBA history? That’s coming up right after the break.

::

Maddox: Welcome back. Matt, so, I think the search for an actor that could play Kareem Abdul-Jabbar kind of represents what it’s like to be Kareem Abdul-Jabbar himself, if that makes sense.

Brennan: Can you elaborate on this idea? ’Cause I like it, but I don’t have any idea where you’re going with it yet.

Maddox: That’s fine. Listen to “Winning Time” co-creator Jim Hecht describe his relief when the team finally found Solomon Hughes, who’s the actor who plays Kareem Abdul-Jabbar.

Jim Hecht: It’s just, it’s so lucky. Like how do you find a guy who’s like 7 foot, he played college basketball, who’s also a professor, you know, at a major university. And by the way, also just one of the best people I’ve ever met, like, you could not find a nicer guy on the planet.

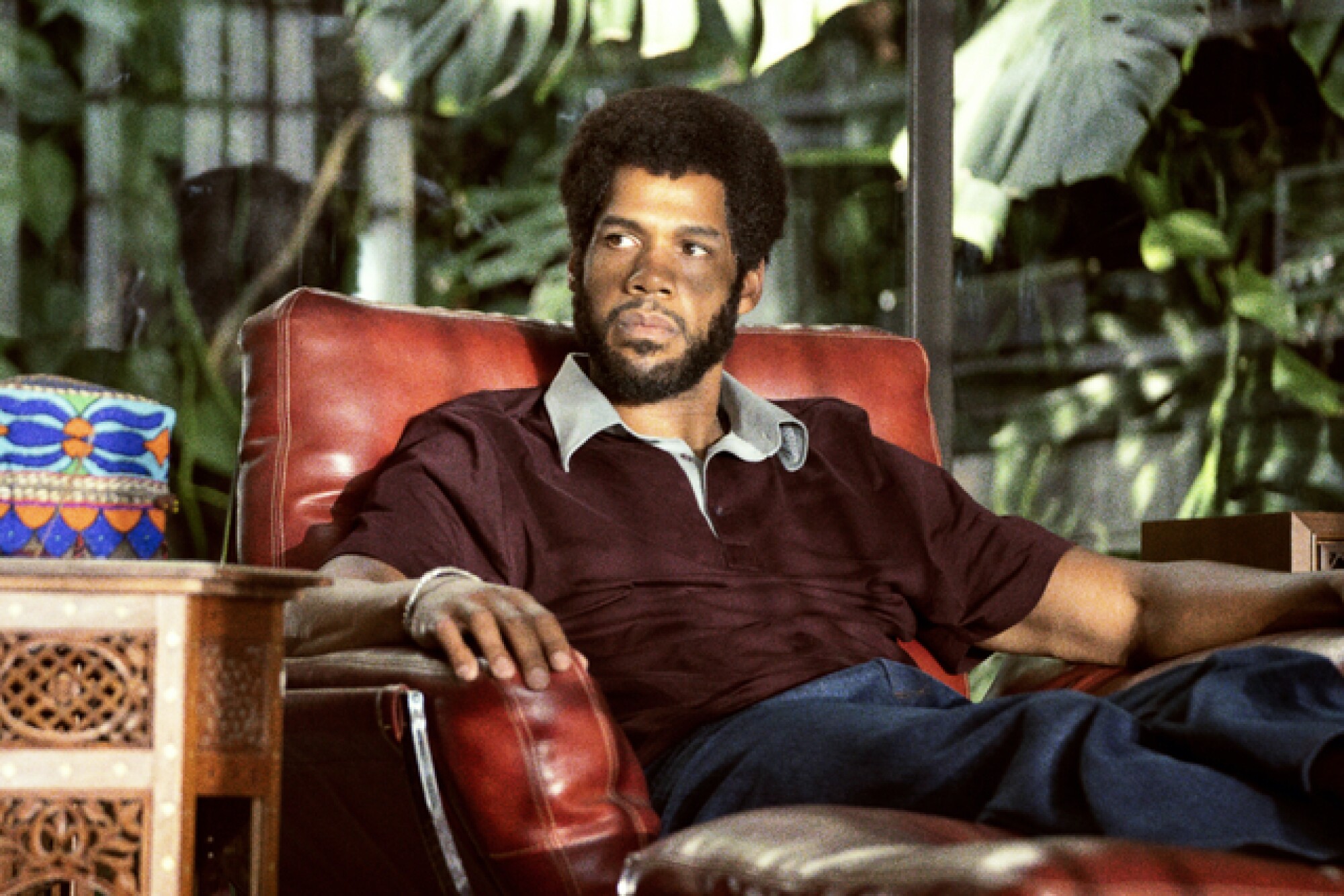

Solomon Hughes as Kareem Abdul-Jabbar in “Winning Time.”

(Warrick Page/HBO)

Brennan: Solomon Hughes grew up in Southern California.

Solomon Hughes: I lived in Riverside, and Riverside is approximately an hour outside of L.A., during the era of ’80s, during the Lakers dominance, so we were big fans as a family. Watched them pretty religiously on television. And Kareem was the literal and figurative center of our appreciation for the team because of his history. Because of just how he did — the contributions he’s made to the world. The way he’s stood up for the oppressed and how he always was resistant to this idea of being boxed into just being a basketball player.

Maddox: And that’s kind of why Solomon is sort of uniquely qualified to play the role of Kareem. He’s always thought of himself as more than just a basketball player.

Hughes: I feel like I had this experience when I played basketball, where I was often told by coaches that I didn’t love the game to the point where I only thought about the game.

Brennan: Hughes has a PhD in education and has been a professor at both Duke and Stanford. It’s a pretty legitimate resume. As a former academic, I can tell you that that is an enviable resume.

Maddox: Yeah. And he was fascinated by some of the more complex parts of Kareem’s story.

Hughes: Every time I learned something new about him, I feel it, it just crystallizes that this man is one of the most fascinating people in the history of this country. Just thinking about just the width and the breadth of how he has contributed yet as a writer, as a spokesperson, as an activist.

His book “Giant Steps,” his autobiography, that’s one of the first big books that I read as a kid growing up, right alongside the autobiography of Malcolm X. I think Kareem has written like 14 books? There’s books where he’s talking about history, Black history. So I wanted to read what he wrote about. I was also interested in the things that he was interested in.

So obviously if you’re a fan of Kareem’s, you know that jazz music is really central to who he is as a person. And he had this famous collection of jazz albums. And the fact that he knew Thelonious Monk when he was coming of age in New York, it’s like, what?

I always joke that if that’s the one thing Kareem could brag about, he has the most interesting story at every cocktail party he goes to, but then he’s also a six-time MVP, you know, an NBA champion, a jazz aficionado, a writer, just such a complex, complex figure, such a fascinating and influential figure. So I wanted to learn about what he said about himself. I wanted to learn about the ecosystems that he came up within. So reading about New York, especially in that era, was important to me.

READ MORE >>> Kareem Abdul-Jabbar: Remembering Central Avenue, L.A.’s jazz oasis

Brennan: But Kareem Abdul-Jabbar was operating in a culture that made it uncomfortable for him to embrace that complexity, as a Black man in America in the 1960s and 1970s and as someone who spent his entire adult life in the spotlight.

In Palm Springs for training camp in September 1980 are Lakers coach Paul Westhead, left front, Kareem Abdul–Jabbar, Jamaal Wilkes, Jim Chones, Michael Cooper, Brad Holland, assistant coach Pat Riley and Mark Landsberger. On the diving board are Magic Johnson and Norm Nixon.

(Ben Olender/Los Angeles Times)

Hughes: I mean, there were so many different things that were going on. It’s like, when you think about sportswriters, especially in that era, right? Not many sportswriters looked like him. So he’s interacting with these journalists who kind of see him from a distance.

Right. And the reality is like, there’s — especially in that era, right? — the backdrop that racism, etc., is to so many of these different conversations.

You talk about the hyper-visibility of being someone like Kareem. You have these political perspectives that make you somewhat of an outlier. You’re also 7-feet-2. And so just this idea of how to exist in this space where everything you say is scrutinized, where you ultimately, you know, your vision for this planet, for this world, is that people get along and that people can enjoy a life of equity.

Maddox: Solomon Hughes talked about how Abdul-Jabbar prioritized his beliefs above his basketball career and above his own personal gain, even before he was an established pro.

Hughes: When you think about the decision that Kareem made when he went to the Cleveland summit as a sophomore in college to essentially support Muhammad Ali and his protesting the Vietnam War — the risk involved in that, right? I mean, it’s just such a profound amount of risk. Especially as this is the era where the commercial opportunities, right? The brand opportunities are starting to come together for athletes. And the fact that he went and was really frontline in this conversation.

Maddox: Matt, I came across a story about Kareem that illustrates this point almost perfectly.

So when Kareem was turning pro, he had two offers, one from the Milwaukee Bucks, one from the Brooklyn Nets. And he’s told both teams that he was only going to take one offer. And when they did make their offers and he chose Milwaukee, Brooklyn made a counteroffer that was like double the money and offered him 5% of the Brooklyn Nets franchise. And Kareem turned it down and kind of scolded the ABA’s commissioner at the time because, he said, this is not a respectable way to do business.

Brennan: So we’re talking about someone who turns down what must now be worth in the tens, or even hundreds of millions of dollars in order to protect his integrity. And this is not because of some kind of external system of rules, but because of a rule that he imposed on the negotiation process himself.

It’s interesting: I think talking about his business acumen and this moment of the leagues merging leads to an important broader point because Kareem Abdul-Jabbar was the league’s biggest star at this transitional moment that we’ve been talking about all season. In the league, in the culture, in business, in American politics. And until you unpack all of those, you can’t really know Kareem either — which is what we’re going to get to right after this break.

::

Maddox: Welcome back.

Brennan: You know, Kareem, it occurs to me that the more you learn about Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and his long career, the more likely you are to reconsider your preconceived notions about him.

Maddox: OK, why do you say that?

Brennan: Jim Hecht told us a story that I think sort of gets at this.

Hecht: He did tell people to eff off, you know, when they asked for autographs. I, as a kid, had a run-in with Kareem where, as my dad tells it, when I was standing outside the Forum and waiting for an autograph. Kareem was basically not going to stop. And I basically remember seeing knees come at me and my dad lifting me out of the way. And he didn’t love, didn’t seem to have a great love for fans or the media or any of those people. And, so, not only does Solomon bring a lot to it, but our writers, I think, really dug in beyond that surface level of Kareem and what people know and see.

Brennan: In “Showtime,” the book on which “Winning Time” is based, Jeff Pearlman says some things — like that Kareem hates white people — that probably paint with too broad of a brush. But he also includes stories that you might not know about Kareem. Like at one point his house burned down. At one point his manager fleeced him of a bunch of money. He had a coach call him a racial slur when he was in high school. You start to get a sense of someone who had been wounded enough times to justify their self-protective measures.

READ MORE >>> $55-million action alleges financial mismanagement: Abdul-Jabbar sues former manager

Maddox: Yeah. And I think Jeff Pearlman when he wrote “Showtime,” probably leaned too hard into that mean image of Abdul-Jabbar. But since, it seems like he’s kind of softened a little bit.

Pearlman: I almost feel like I was a little too hard on him in the book. That guy was a museum piece from the time he was very young, and everywhere he walked, [people said,] “How’s the weather up there? How’s the weather up there? What’s it like up there?” And after a while you just want to start ignoring people.

Lakers owner Jerry Buss talks with Kareem Abdul-Jabbar in the locker room after a game in February 1983.

(Los Angeles Times)

So it’s a classic example, especially with the Black athlete being labeled as brooding and moody. And why is he always scowling? The truth of the matter is he was just tired of people asking him what’s the weather like up there and staring at him all the time.

And then of course he changes his name from Lew Alcindor to Kareem Abdul-Jabbar while he’s in Milwaukee. Everyone who’s white and in the NBA discourages him from doing so. A lot of people refuse to call him Kareem Abdul-Jabbar; they still call him Lew Alcindor, just like Muhammad Ali got that with Cassius Clay. And he just built up this wall of distrust. And again, I think I was too hard on him, because if you really think about it, it makes sense.

Maddox: “Winning Time” picks up when Kareem Abdul-Jabbar is 32 years old. And to this point in his life, he’d really actually been through a lot. In 1967, Abdul-Jabbar sat alongside Jim Brown, Muhammad Ali and Bill Russell to support Muhammad Ali as he was protesting being drafted to the Vietnam War. At the time, Abdul Jabbar was just 20 years old. And the next year was 1968 and that’s when he refused a spot on the U.S. Olympic team, which is a guaranteed gold medal, especially with him on the team. And he refused that spot because he was protesting the treatment of Black people in America.

So on the one hand, Abdul-Jabbar clearly considers himself as coming from this long line of powerful civil rights activists who are also athletes at the top of their professional sports.

Brennan: And on the other hand, he has to watch as a new generation of players comes in and maybe benefits from some of the doors that he’s opened.

Maddox: That’s something that Rachel Laws Myers talks about further:

Myers: And then you kind of get to ’80s into ’90s, and you start, you see O.J. Simpson and you see Michael Jordan and you start to see this booming profitability off of not being political. I’ve always seen Kareem more of as this serious, really kind of wise man who has always had, I think, this kind of political lens. He’s written that he was really influenced by the leaders of the ’50s and the ’60s, the Muhammad Ali, the Malcolm X.

There’s something to be said about the real choice, and kind of act of bravery of putting it on the line and being willing to sacrifice — even with Tommie Smith and John Carlos in the ’68 Olympics, right? Stripped of medals, all of this, etc. Fast-forward, right, they’re being honored in the athletic hall of fame and, like, [Smith and Carlos are hearing] “we’re so sorry” and “our mistakes.”

And then also the very real, again, choice when you’re faced with, “Hey, here’s some money for this or this, that, and the third,” or “Here’s this opportunity. And if you’d like this opportunity, we’re going to set some parameters on how you’re going to engage. Right. And that might be, you’re not going to talk about the political situation, right? You’re you’re not gonna mention X, Y and Z.”

MB: “Winning Time” highlights this generational divide when Spencer Haywood goes to visit Kareem Abdul-Jabbar at his house and talks about the tension that has arisen between the sort of two factions here.

[“Winning Time” clip: Spencer Haywood character: I saw his face when he was hugging you, hanging off your neck like a damn koala bear.

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar character: You know I can’t dig the clown show, the dancing and grinning for the crowd.

Haywood character: So you mad ‘cause he happy.

Abdul-Jabbar character: You know it’s more than that. When we came up, we put it on ourselves to stand for something more. We took the boos. We took the hate. Black man, you took the league to the Supreme Court. It was a racist-ass rule, and you made a difference.]

Brennan: How the culture was changing under Kareem Abdul Jabbar’s feet informed how the writers of “Winning Time” sort of shaped his character in the show, according to Jim Hecht.

Hecht: And now he comes into Los Angeles in the ’80s and all of a sudden, it’s just about like, what color BMW do you have? If you’re standing there in Los Angeles in 1980 on the verge of the Reagan revolution and you open the paper and it really did, like, he talked about “make America great again,” that has to be so hugely disappointing. I can understand why you’d have some reticence about dealing with people in that culture at all.

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar presents a Lakers jersey to President Reagan at the White House in June 1985, holding it in front of coach Pat Riley. Looking on are Bryon Scott, to the left of Reagan, and James Worthy.

(Patrick Downs / Los Angeles Times)

Maddox: I just feel like people don’t know what to make of Kareem Abdul-Jabbar. Like, they think he’s moody and broody, but also brilliant. And they understand where he comes from and they don’t judge him for how he interacts with the public.

Brennan: I mean, the thing that occurs to me that you’re kind of dancing around is the difference between being respected and being loved.

Maddox: Yeah.

Brennan: The way that people talk about Kareem Abdul-Jabbar comes from a place of respect. It’s sort of logic based. It’s a brain feeling.

Maddox: Yeah.

Brennan: Whereas the way that people talk about Magic is love. It’s like a heart feeling.

Maddox: Here’s Bill Plaschke again.

Plaschke: He’s a brilliant pioneer, and such integrity. Such strength. All he’s been through — his fight for social justice. He wrote a story for our paper that just got a million views and people couldn’t get enough of it. Can’t get enough of his wisdom, but he never had the magnetism.

Maddox: The sports world doesn’t seem to be giving Kareem Abdul-Jabbar his due, but his social justice work and his life’s mission have been recognized. In 2012, he was selected by then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton to be a U.S. global cultural ambassador. And then in 2016, President Barack Obama awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom. So it’s like, his impact is stronger off the court, despite being the best scorer that the NBA has ever seen.

Brennan: So I think the argument that we’re making then is that Kareem Abdul-Jabbar’s really important political advocacy work over the years, and his interest in culture, has actually unfairly taken him out of the GOAT conversation.

Maddox: That’s what it feels like. Or am I off there?

Brennan: Uh, well, I’m not having the GOAT conversation regularly in my day-to-day life, so I don’t really know.

It occurs to me that both Michael Jordan and Magic Johnson have produced major docu-series about their own careers. Kareem Abdul-Jabbar has produced docu-series about major Black historical figures. Like that’s a very distinct approach to one’s sort of cultural power in the world. And I don’t think you have to make kind of a moral judgment on one side or the other about that approach. But I think that contrast is telling.

For someone who doesn’t know basketball very well, there were two players in this story who I knew their names going in, and I would recognize those names by first name alone: Magic and Kareem. And the one who I feel like I really didn’t have a good understanding of until watching the show and talking to you about him is Kareem. Magic feels like more of a known quantity to me, maybe that’s ‘cause he wears his heart on his sleeve a little bit more. Maybe that’s because he was prominent in the slightly later era where I was paying a little more attention. Maybe it’s because of HIV diagnosis and the sort of life that he’s lived after his career. But to me, the fact that Kareem could be known by his first name alone and yet have very little known actually about him kind of says it all.

READ MORE >>> A last hurrah: For Abdul-Jabbar, a season of farewells will be capped today

::

Maddox: Do you have a favorite actor of all time?

Brennan: Oh, God. Yeah. Probably, like, Cary Grant.

Maddox: Dude, Cary Grant?

Brennan: Yeah, why would — don’t, don’t say it like that. That is not a strange selection for favorite actor of all time.

Maddox: Do you know who Sean Connery is? Have you ever heard of Sean Connery?

Brennan: He’s dashing, he’s funny, he’s completely charming. He was in a bunch of great movies. He could do drama. He could do comedy. He worked with all the great directors of his era.

Maddox: Was he ever Bond?

Brennan: No.

Maddox: So how could he be the greatest actor of all time if he was never Bond?

Brennan: I am going to shut off this Zoom if you don’t stop. Cary Grant is basically like the proto Bond. He was Bond before Bond. He was that suave and sexy without Bond existing yet.

Maddox: See, but this is the generational difference, right? This is like, who was more dominant, Wilt Chamberlain or Shaq? Who’s better, Cary Grant — but now you’ve got Daniel Craig, I mean, that guy…

Brennan: I thought you were talking about the generational difference between you and I …

Maddox: Oh, no!

Brennan: … and I was about to punch you through the screen. I’m not that much older than you.

Maddox: I guess you could argue that Cary Grant — well, this is how these GOAT conversations go, you know?

Brennan: Yeah. Although I would say that the difference here, and what I think makes the sports one almost more interesting, is, like, statistics can give you a sense — or maybe it’s an illusion — of objectivity. Whereas like there isn’t, I mean, I guess with an actor you could kind of compare who won the most Oscars, but as we have discovered, the Oscars are a flawed thing.

Maddox: Yeah. They have their issues, don’t they?

Brennan: So there truly is no one-to-one comparison that you can make between actors. It’s purely a heart-gut reaction.

Maddox: Totally. Yeah. No, totally.

Brennan: We have gone so far off the rails here.

Additional resources

Kareem Adbul-Jabbar, “Coach Wooden and Me: Our 50-Year Friendship On and Off the Court” (2017)

— and Peter Knobler, “Giant Steps: The Autobiography of Kareem Abdul-Jabbar” (1983)

— and Mignon McCarthy, “Kareem” (1990)

— and Raymond Obstfeld, “Becoming Kareem: Growing Up On and Off the Court” (2017)

— and Raymond Obstfeld, “On the Shoulders of Giants: My Journey Through the Harlem Renaissance” (2007)

— and Raymond Obstfeld, “What Color Is My World? The Lost History of African American Inventors” (2012)

— and Stephen Singular, “A Season on the Reservation: My Sojourn with the White Mountain Apaches” (2000)

— and Alan Steinberg, “Black Profiles in Courage: A Legacy of African-American Achievement” (1996)

— and Anthony Walton, “Brothers in Arms: The Epic Story of the 761st Tank Battalion, World War II’s Forgotten Heroes” (2004)

Rachel Laws Myers, “Race and Sports: A Reference Handbook” (2021)

Jeff Pearlman, “Showtime: Magic, Kareem, Riley, and the Los Angeles Lakers Dynasty of the 1980s” (2013)