Rodney Brooks knows the difference between real technological progress and baseless hype.

One of the world’s most accomplished experts in robotics and artificial intelligence, Brooks is the co-founder of IRobot, the maker of the Roomba robotic vacuum cleaner; co-founder and chief technology officer of RobustAI, which makes robots for factories and warehouses; and the former director of computer and artificial intelligence labs at MIT.

So when, in 2018, the Australian-born Brooks encountered a wave of unwarranted optimism about self-driving cars — “people were saying outrageous things, like, Oh, my teenage son will never have to learn to drive” — he took it as a personal challenge. In response, he compiled a list of predictions about autonomous vehicles, artificial intelligence, robots and space travel, and promised to review them every year until Jan. 1, 2050, when, if he’s still alive, he will have just turned 95.

I don’t think we’re limited in our capability to build human-like robots, ultimately. But whether we have any idea how to do it right now or whether all the ways we think are going to work are remotely correct, that’s totally up for grabs.

— Robotics and AI expert Rodney Brooks

His goal was to “inject some reality into what I saw as irrational exuberance.”

Each prediction carried a time frame — something would either have occurred by a given date, or no earlier than a given date, or “not in my lifetime.”

Newsletter

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Brooks published his fifth annual scorecard on New Year’s Day. The majority of his predictions have been spot on, though this time around he confessed to thinking that he, too, had allowed hype to make him too optimistic about some developments.

“My current belief is that things will go, overall, even slower than I thought five years ago,” he wrote this year.

As a veteran technologist, Brooks has ideas about what makes laypersons, or even experts, excessively optimistic about new technologies.

People have been “trained by Moore’s Law” to expect technologies to continue improving at ever-faster rates, Brooks told me.

His reference is to an observation made in 1965 by semiconductor engineer Gordon Moore that the number of transistors that could fit on a microchip doubled roughly every two years. Moore’s observation became a proxy for the idea that computing power would improve exponentially over time.

That tempts people, even experts, to underestimate how difficult it may be to reach a chosen goal, whether self-driving cars, self-aware robots, or living on Mars.

“They don’t understand how hard it might have been to get there,” he told me, “so they assume that it will keep getting better and better.”

One example is driverless cars, a technology with limitations that laypersons seldom recognize.

Brooks has written about his experience with Cruise, a service using self-driving taxis (no one in the front seat at all) in parts of San Francisco, Phoenix and Austin, Texas.

In San Francisco, Cruise operates only between 10 p.m. and 5:30 a.m. — that is, when traffic is lightest — and only in limited parts of the city and in good weather.

On his three Cruise trips, Brooks found that the vehicles avoided left-hand turns, preferring to make three right turns around a block instead, drove painstakingly slowly and once tried to pick him up in front of a construction site that would have exposed him to oncoming traffic.

“The result is that it was slower by a factor of two over any human operated ride hailing service,” Brooks wrote. “That might work for select geographies, but it is not going to compete with human operated systems for quite a while.” It’s also “decades away from profitability,” he judged. In his annual scorecard this year, he predicted that “there will be human drivers on our roads for decades to come.”

The annual scorecard is one of many outlets Brooks relies on to temper “irrational exuberance” about technology in general and AI specifically. He has been a frequent contributor to IEEE Spectrum, the house organ for the leading professional society of electronics engineers.

In an article titled “An Inconvenient Truth about AI” in September 2021, for instance, he noted how every wave of new developments in AI was accompanied by “breathless predictions about the end of human dominance in intelligence” amid “a tsunami of promise, hype, and profitable applications.”

In reality, Brooks wrote, almost every successful deployment of AI in the real world had either a human “somewhere in the loop” or a very low cost of failure. The Roomba, he wrote, functioned autonomously, but its most dire failure might involve “missing a patch of floor and failing to pick up a dustball.”

When IRobots were deployed in Afghanistan and Iraq to disable improvised explosive devices, however, “failures there could kill someone, so there was always a human in the loop giving supervisory commands.”

Robots today are common in industry and even around the home, but their capabilities are very narrow. Robot hands with true human-like dexterity have not advanced much in 40 years, Brooks says. That’s also true of autonomous navigating around any home with its clutter, furniture and moving objects. “What is easy for humans is still very, very hard for robots,” he writes.

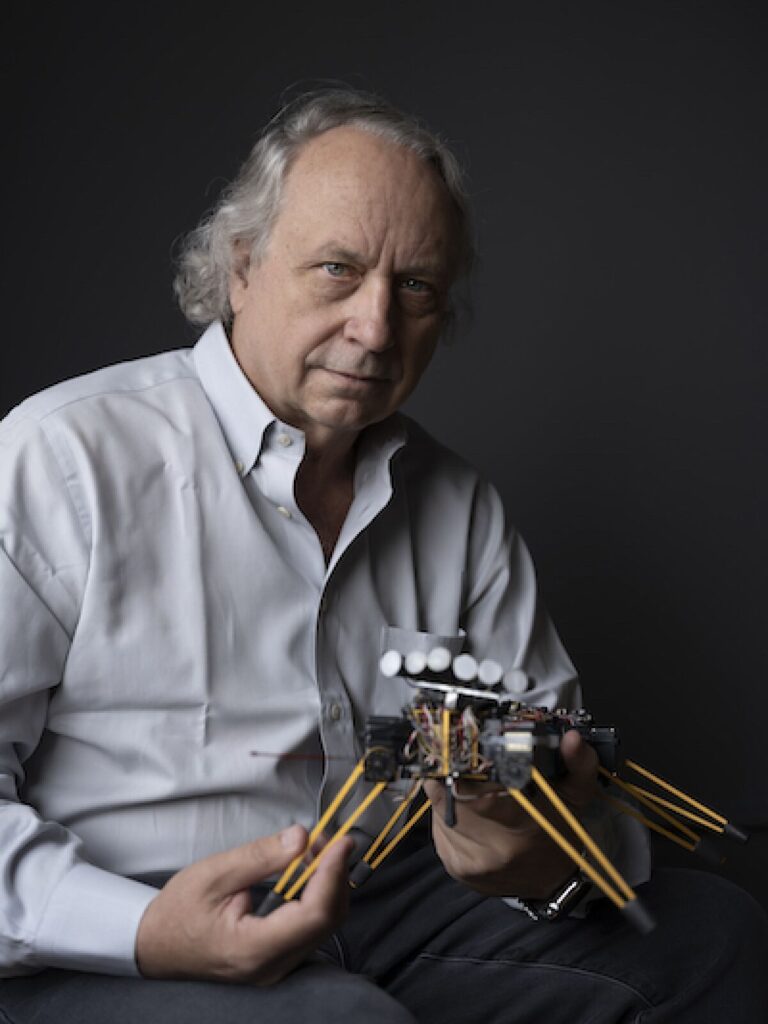

Rodney Brooks

(Christopher P. Michel)

As for ChatGPT, the AI prose generator that has garnered inordinate interest by high-tech enthusiasts, along with warnings that it may launch a new era of machine-driven plagiarism and academic fakery, Brooks argues for caution.

“People are making the same mistake that they have made again and again and again,” he writes in his scorecard, “completely misjudging some new AI demo as the sign that everything in the world has changed. It hasn’t.”

ChatGPT, he writes, is replicating patterns in a human prompt, rather than showing any new level of intelligence.

That doesn’t mean that Brooks doubts the eventual creation of “truly artificial intelligences, with cognition and consciousness recognizably similar to our own,” he wrote in 2008.

He expects “robots that will roam our homes and workplaces … to emerge gradually and symbiotically with our society” even as “a wide range of advanced sensory devices and prosthetics” emerge to enhance and augment our own bodies: “As our machines become more like us, we will become more like them. And I’m an optimist. I believe we will all get along.”

That brings us back to Brooks’ 2023 scorecard. This year, 14 of his original predictions are deemed accurate, whether because they happened within the time frame he projected, or failed to happen before the deadline he set.

Among them are driverless package delivery services in a major U.S. city, which he predicted wouldn’t happen before 2023; it hasn’t happened yet. On space travel and space tourism, he predicted a suborbital launch of humans by a private company would happen by 2018; Virgin Atlantic beat the deadline with such a flight on Dec. 13, 2018.

He conjectured that space flights with a few handfuls of paying customers wouldn’t happen before 2020; regular flights at a rate of more than once a week not before 2022 (though perhaps by 2026); and the transport of two paying customers around the moon no earlier than 2020.

All those deadlines have passed, making the predictions accurate. Only three flights with paying customers happened in 2022, showing there’s “a long way to go to get to sub-weekly flights,” Brooks observes.

Brooks is consistently skeptical of the projections of our most often-quoted technology entrepreneur, Elon Musk, who Brooks notes “has a pattern of over-optimistic time frame predictions.”

A moon orbit of paying customers in the Falcon Heavy capsule of Musk’s SpaceX doesn’t look possible before 2024, Brooks observes. The landing of cargo on Mars for later use by humans, which Musk once forecast to happen by 2022, looks like it won’t happen before 2026, and even that date is “way over-optimistic.”

Musk still hasn’t fulfilled his 2019 promise that Tesla would place 1 million robo-taxis on the road by 2020 — that is, a fleet of autonomous cars summoned through an Uber-like Tesla app. “I believe the actual number is still solidly zero,” Brooks wrote.

As for Musk’s dream of regular service between two cities on his Hyperloop underground transport system, Brooks places that in the “not in my lifetime” pigeonhole.

Several of Brooks’ predictions remain open-ended, including some involving the market for electric vehicles. In his original forecast, he projected that EVs would not reach 30% of U.S. car sales before 2027 or 100% before 2038.

The growth rate in EV sales became turbocharged in 2022 — increasing by 68% in the third quarter over the same quarter a year earlier. If that growth rate continued, then EVs would constitute 28% of new car sales in 2025.

That presupposes that the forces driving EV adoption continue. The head winds, however, shouldn’t be underestimated. EV sales may have spiked because of the huge run-up in gasoline prices in 2021 and last year, but that inflationary trend has now disappeared. Battery factories may take longer to come online than expected, which could produce a shortage of these all-important components and drive EV prices higher.

“Clearly something is going on,” Brooks writes, though “the jury is still out” on whether the U.S. will see 30% EV market share by 2027.

Brooks doesn’t wish to stifle human aspirations to build robots, AI systems, or space exploration.

“I’m a technologist,” he told me. “I build robots — that’s what I’ve done with my life — and I’ve been a space fan forever. But I don’t think it serves people well to be so overly off-the-charts optimistic” that they ignore the hard problems standing in the way of progress.

“I don’t think we’re limited in our capability to build human-like robots, ultimately,” he says. “But whether we have any idea how to do it right now or whether all the ways we think are going to work are remotely correct, that’s totally up for grabs.”

He compares the dream to that of medieval alchemists searching for how to transmute lead into gold. “You can do it now with a particle accelerator to change the atomic structures, but back then they didn’t even know there was an atomic structure. We may well be like that on human-level intelligence, but we don’t have a clue how it works at all.”