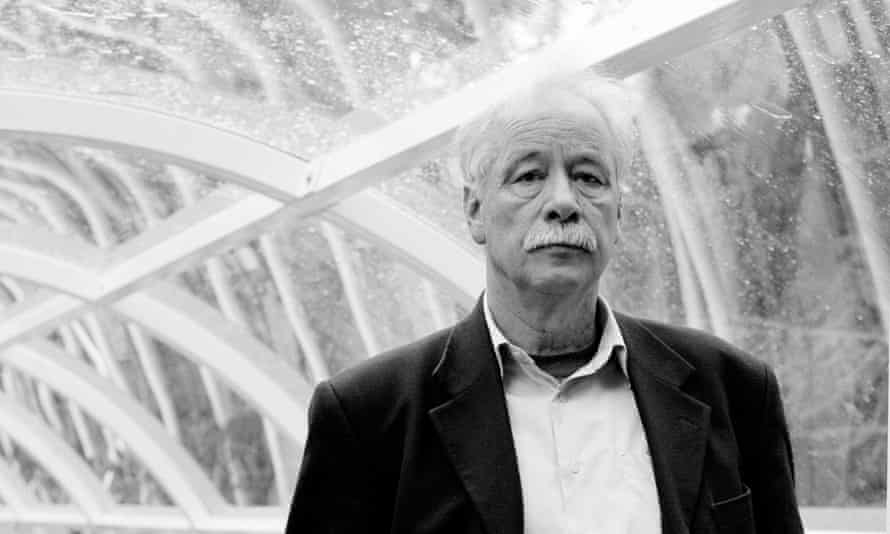

German writer WG Sebald is regularly named one of the most influential writers of recent decades. He referred to his genre-defying books as prose fiction – not-quite-novels, not-quite-autobiographies, not-quite-nonfiction – but with elements of all. Examining loss, exile, memory and trauma, they still feel relevant today. To mark the 30th anniversary of Sebald’s book The Emigrants, journalist and PhD candidate Sandra Haurant suggests where those new to Sebald should start.

The entry point

The first of Sebald’s works to reach an English readership, The Emigrants, is a collection of four short stories. It was published in German in 1992, and its English translation, by Michael Hulse, came out in 1996. Sebald biographer Carole Angier calls it “the Sebald book par excellence”.

As with his other texts, we are never quite sure what is “real” and what Sebald has invented here. Its central themes – including loss, memory, displacement, and the relentlessly reverberating consequences of trauma – reappear in all his work, and the text is punctuated with black and white photos, another hallmark.

Angier first read The Emigrants when she was asked to review it, and writes: “When I closed the cover on the last story late that night, I was like someone in love – elated.” It would be a stretch to call the stories undilutedly uplifting; what they are, though, is melancholic, heart-breaking and beautifully written.

The page-turner

Austerlitz tells the story of Jacques Austerlitz, an academic who has an epiphany in a waiting room at London’s Liverpool Street station, recognising this as the place in which he first arrived in Britain as a small boy, travelling on the Kindertransport.

It is a period that memory has erased, and uncovering the rest of his history – his parents’ fates, his birthplace, his mother tongue – requires careful excavation. In other hands, this might have been a straightforward quest story, but Sebald does things differently, subtly, creating a page-turner despite long passages where very little seems to happen.

With long, winding sentences and reported speech, it is written (and translated into English by the revered Anthea Bell) with a poetry and sensitivity that earn Sebald’s prose adjectives such as meditative, dreamlike and contemplative.

It’s worth persevering with

Vertigo, first published in German in 1990 and English in 1999 (translation by Hulse) opens with a biography of a Marie-Henri Beyle, the real name of the French realist writer Stendhal. Brief but oddly detailed, it lays out Beyle’s role in the Napoleonic wars and examines his mental and physical ailments, including a venereal infection and the symptoms of syphilis: “difficulties in swallowing, swellings in his armpits, and pains in his atrophying testicles [which] troubled him especially”.

Among these accounts, there are moments of transcendence – the “longing for love” Beyle feels in Italy in the form of a “curious lightness such as he had never known”; the hikes in the Lombardy mountains where “only the larks could be heard as they climbed the heavens”. If you can make it past the (often unpleasant) minutiae, the striking contrasts between pain and beauty form part of that mesmerising prose Sebald does so well.

The one to give a miss

Sebald’s first literary work was After Nature, a book-length prose poem published in German in 1988, then translated into English by Michael Hamburger and published in 2002, a year after Sebald’s death. It speaks of “the themes of migration, stillness and remembering which were his recurrent preoccupations,” writes Andrew Motion in the foreword. Perhaps one for the completists – along with his essay collections, A Place in the Country and On the Natural History of Destruction.

The one you’ll want your friends to read

Sometimes you foist newly beloved books upon friends because of characters they’ll identify with, or a plot twist that leaves you reeling. The urge to share The Rings of Saturn is every bit as strong, but it’s hard to explain exactly why they should read it.

On the face of it, it’s not an easy sell; the narrator (who may or may not be Sebald himself) embarks on a walk along the Suffolk coast “in the hope of dispelling the emptiness” brought on after completing a “a long stint of work”. Part travelogue, part ramble through the narrator’s vast, troubled and troubling thoughtscape, it is also, as Robert McCrum put it, “a strange and deep response to the atrocities of history”. The meandering prose takes in topics as peculiar and diverse as “The natural history of the herring,” “The battle of Sole Bay” and “The Dowager Empress Tz’u-hsi.”

Accompanied once more by those black and white photographs (the first shows nothing but an uninspiring reinforced-glass window and “a colourless patch of sky”), memories, histories, and echoes of trauma flow on to the page, leading the reader along a strange path and past so many terrible scenes that you emerge from the book blinking and desperate to talk to someone else who has also seen what you’ve seen. Maybe just give them the book, and save the conversations for later.