Caroline Grace has always enjoyed vintage technology. An IT tech in the Mid-Ohio Valley, they collect retro games, laser discs and cassette tapes, but mostly, vinyl records. Their collection is in the thousands, and hundreds of those are video game soundtracks. “I’ve been a big fan of games all my life,” says Grace. “Some of my earliest memories are playing games like Wonder Boy III: The Dragon’s Trap and Goof Troop with my dad and brother. I get positive feelings from listening to the Wonder Boy III music now. I have a lot of pleasant memories of playing it with my family back in the day.”

The idea of buying video game soundtracks on vinyl may seem counter-intuitive: the most hi-tech digital entertainment medium meeting this fragile relic of the analogue era. But gaming albums have been steadily rising in popularity since the early 2010s. Partly that’s thanks to the wider vinyl revival, but it’s also due to the efforts of specialist record labels such as Data Discs, which produces beautiful albums based on vintage video games. “When we started the label in late-2014 there wasn’t really anyone releasing game soundtracks on vinyl,” says co-founder Jamie Crook. “We had been half-joking about trying to release Streets of Rage for the best part of a decade and we’re still surprised that no one else beat us to it. It just seemed abundantly clear that game soundtracks were going to be one of the next growth areas, alongside Japanese ambient, especially after the huge popularity of film soundtrack labels from 2012 onward.”

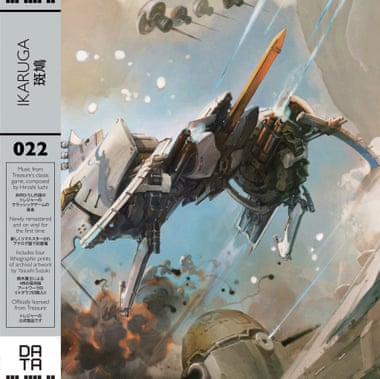

The idea became a reality when Cook sent a speculative email to Streets of Rage composer Yuzo Koshiro: he was on board immediately, as was Sega Japan (“though I think they were also a little bewildered”). Consequently, Data Discs was able to license a number of releases spanning Sega’s history, from Sonic to Shenmue, and has since broadened to other classic Japanese titles such as Okami, Ikaruga and surprise best-seller Policenauts, the old cyberpunk thriller from Metal Gear creator Hideo Kojima.

Nostalgia seems to be a major draw for many collectors. Alongside Data Discs, labels such as movie soundtrack specialist Mondo and hip New York-based indie Ship to Shore PhonoCo also produce high quality albums for classic games. “Nostalgia plays a big part in my vinyl collecting – I will go out of my way to acquire records for games that I enjoyed as a kid,” says Chris Hansen, an IT contractor for the Department of Homeland Security in Mississippi. “I got into collecting vinyl in 2016 when I heard about Mondo’s release of Castlevania. I own every Castlevania game, it’s my favourite series, so I had to get the record. When I started looking into other releases, I discovered that Data Discs had put out Streets of Rage and Streets of Rage 2 on vinyl. I’ve been hooked ever since.”

But it’s not all about the past; a huge number of contemporary video games are accompanied by vinyl soundtrack releases, whether that’s an orchestral score for a bestselling Triple A blockbuster, or an electronic soundtrack for a cult indie game composed entirely by a lone musician. For small studios, it can be tough to make a living from game sales alone in such an over-saturated market, so selling merch to a dedicated fanbase is an important source of revenue.

There is also an important community element to video game vinyl. Releases tend to be limited editions and not always widely marketed, so fans meet up on Discord servers and Reddit forums to swap tips and compare collections. “We sometimes help each other get our personal ‘holy grails’,” says Pete Boyle, a collector based in Leeds. “Last year, I mentioned in passing that I missed the original release of the Firewatch soundtrack by Chris Remo. Minutes later I received a message from someone offering to sell it to me at cost plus post. It was in my hands less than two weeks later! We look out for one another. I have made some incredible friends for life.”

In the early 2010s, Austin Wintory’s beautiful cello-led soundtrack for Journey and the 1980s-splashed electropop of Hotline Miami 2 showed how varied and musically accomplished game scores had become. Now, from global Final Fantasy concert tours to BBC Radio 3’s excellent Sound of Gaming programme to the forthcoming gaming concert at the BBC Proms, game soundtracks have been accepted as an art form alongside film scores. For many players, listening to game music is a personal, immersive experience, because we may have listened to it not just through a 90-minute film, but tens of hours of play.

“The concept of dynamic music – or music that changes to your environment or actions – is unique to games,” says Sound of Gaming presenter Louise Blain. “As players, we have come to rely on music to tell us we’re in danger, to react when we draw our swords, and tell us to calm down when the coast is clear. It is our soundtrack, no one else’s.

“Film music never needs to fill the gap when we get distracted and wander off the beaten path to see what we can find hiding deeper in the woods. Red Dead Redemption 2 composer Woody Jackson jokingly called some of the 60 hours of music he’d composed for the game ‘cowboy yoga music’ because those atmospheric strings had to accompany us everywhere. Game music understands that we want to lose ourselves and take in the scenery as well as ticking off quest lists. It also means that the more time we spend, the stronger our emotional connection can be.”

This is a really vital point. Game music reminds us of places that we have effectively lived in. What’s more, we often play alongside friends, so game music is the sound of a shared journey, bringing to life all the emotions that entails. “There are two soundtracks that will always remind me of a particular time in my life,” says Dutch vinyl collector Jill Verhage. “The soundtrack to Ori and the Blind Forest, as it is one of the last games my best friend played before she passed in 2017, and the soundtrack of Ori and the Will of the Wisps, which always brings me great sadness knowing she never got to experience that game.”

Whatever else motivates collectors, these are beautiful artefacts. At Data Discs, the team spends days sourcing archival video game art for their releases. “On occasion, we’ve tracked down the original paintings, either from the licensor’s vaults or through private art collectors, and have had HD photographs taken,” explains Crook. “The rights for artwork can sometimes be complicated too. For example, for our After Burner II release, we had to license the cover image of the F-14 Tomcat directly from Northrop Grumman, which was a very laborious (and expensive) process, but ultimately worth it.”

Soundtrack albums so easily become an extension of a game’s aesthetic. They are large enough to show off its artwork, and they have an element of discovery too, with extensive liner notes, glossy inserts and luscious packaging. And like video games, they are tactile, concerned with skill and ritual. You treat vinyl records with reverence and care, dropping the needle so that it falls as softly as a good jump in a platform game. And when the music starts, you are transported.