Ken Williams in late 2020 was not yet plotting a full return to the gaming industry, but he was promoting his recently released book, “Not All Fairy Tales Have Happy Endings: The Rise and Fall of Sierra On-Line,” which documents his perspective on the demise of the company he founded.

Astute readers will notice it begins long before the company’s late-’90s disintegration after a major sale that left the Williamses sidelined. It began when Sierra first took venture capital money in the early ’80s, putting it on a path of answering to those who believed they were backing a technological powerhouse rather than a respected publisher of narrative-focused adventure games.

“Once we had accepted venture capital, it became like any other drug,” Ken writes in the book. “No one stops after the first hit. … We brought in a second round of venture capital. I don’t remember why or how much, but it was more money at a significantly higher valuation. We sold a tiny portion of our company to bring in a great deal of money, allowing us even faster growth.”

When Ken started working on what would become “Colossal Cave 3D Adventure,” it was something of a return to an early pastime — learning newer technologies and experimenting with game making for the sake of game making. There was no board, no company. Ken was on a retirement circuit of speaking engagements at online events such as the Vintage Computer Federation East Festival, or VCFEast, to help promote his book, which he self-published and which he says sold approximately 30,000 copies in its first month. This is when he met an unlikely collaborator.

Marcus Mera is no game developer. He is a jeweler by trade and a collector of retro computer wares. He just happened to be presenting at VCFEast, where he was giving a talk on the original 1984 “King’s Quest.” For his part, Mera had no designs on working in the game industry. After all, he used computer software to craft rings, not interactive adventures. But that changed when he met a hero.

Ken and Roberta had left the company they founded, and in the two decades that followed the reasons for their absence had become the stuff of myth. Had they become so disillusioned from selling their company and the drama that followed that games were more or less dead to them?

Not necessarily. Turns out someone just needed to ask them back.

“I just happened to be the guy who was there at the right time,” says Mera, 47. “Probably ignorance is bliss. I didn’t know they didn’t want to do a game and people were begging them to come back. So that ignorance that I wasn’t in the industry didn’t scare me from saying, ‘Hey Ken, wouldn’t it be great if you made a comeback?’ When he found out I was an artist, he said, ‘Hey Marcus, I’ll be in touch with you in a few days.’ A few days later I get a message.”

A scene from “Colossal Cave 3D Adventure,” the new game from Roberta and Ken Williams.

(Cygnus Entertainment)

One problem: “I never made a game before in my life,” Mera says. “I even told that to Ken. He said, ‘Have you ever made a game before?’ Nope. He said, ‘That’s OK, I’ll teach you.’ The whole time I’m nervous. I’m thinking I’m going to get fired. I have zero experience. I just kept the ball rolling and was up day and night. I put on 20 pounds. I was just sitting in front of my computer.”

Ask Ken what it was about Mera that made him want to work with him — to do something he hadn’t done in decades — and he’s nonchalantly sanguine. Basically, he just liked the guy. “He’s a good talker,” Ken says.

“I mentioned I was working on a game and he mentioned he was an artist,” Ken says. “So we partnered, and actually built a game together. I was perfectly happy with it. I liked the development budget because it was absolutely zero. But I showed it to Roberta and she said, ‘Well, that looks like it was an absolutely zero game.’ I didn’t think it was bad.”

Roberta interrupts. “He insists, to this day, it was fine,” she says, stretching out the word “fine” for several seconds for comedic effect.

Mera wanted to seize the opportunity. He had, after all, just created a short game with Ken. Of course he wanted the world to see it. But even he knew it was missing a key ingredient. “Roberta’s like, ‘Marcus, I’ve been there, done that.’ I’m like, ‘Come on, Roberta, let’s make a game!’ She would be looking over Ken’s shoulder and making comments, and Ken would say, ‘You’re either all in, or you’re not in.’ [I]t was not a quick process.”

It was six months.

Mera knew the tide was starting to turn when he and Ken showed Roberta a scene for the game involving some dwarfs. Roberta had instant feedback on how the dwarfs should be redrawn. After updating the scene significantly — but not yet touching the dwarfs — Ken showed the moment to Roberta. She didn’t miss a beat. “All I could hear was, ‘Why hasn’t the dwarf been changed?’”

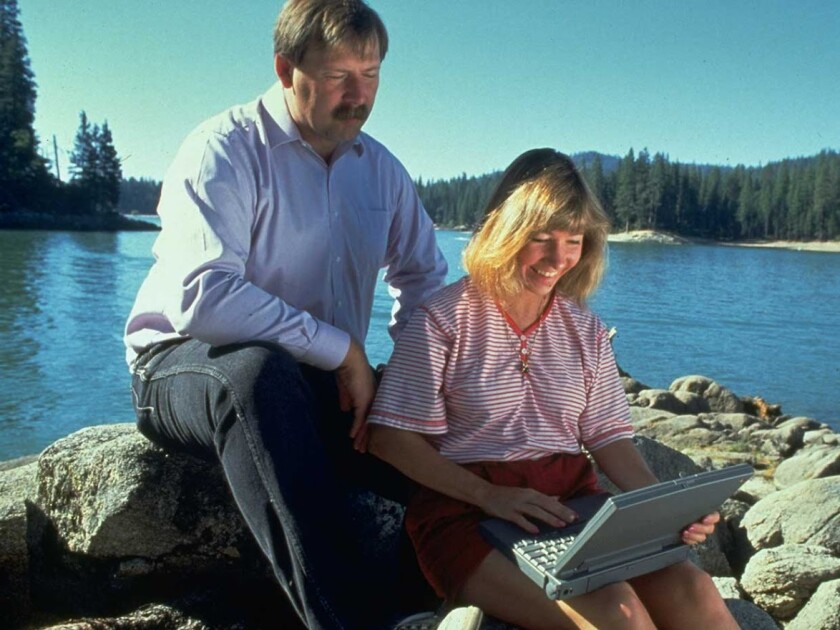

Ken and Roberta Williams, seen in an undated promotional photo, avoided the game industry for more than two decades after leaving the company they founded, Sierra On-Line.

(John Storey)

“This was all Marcus’ fault,” Roberta says. “He kept saying to Ken, ‘You need to get Roberta involved.’ Ken would say to him to be careful what you wish for. Ken was kind of not wanting that to happen because he knew what would happen.”

What would happen is that Roberta would want control of the game and its art, meaning much of what Mera created would be revamped or redone. Mera enjoys a close relationship with the Williamses and has pivoted to focus on his sales and marketing expertise. His passion for the game is indeed infectious, but he remembers he bristled when Roberta remade the game in her vision.

“It was brutal for me to go through that process of seeing my artwork get destroyed,” Mera says. “But she wasn’t wrong. I’m very happy she’s back. It’s her game, so I’m fine with it.”

Early builds of the game shown to media did still include much of the original artwork. Roberta was not entirely pleased that I was shown what she considers a rough demo of the game, one that hadn’t been fully made over with the team of 30 or so staffers she and Ken would go on to hire. “I spent a whole day in serious trouble because she was upset I was going to let you see it,” Ken says. “She considers it in horrible shape.”

“Because I know what’s coming,” Roberta says quickly. “The art you saw — we’ve had that art since March — and we are in the process of an art polish, enhancing it, better animation, more animation, more fun — all the fun, glitzy stuff that I love.”

Since “Colossal Cave” is a remake of a mid-’70s text adventure game, Roberta is careful not to credit herself as the designer of the project, stressing her role as more of a modern interpreter. “I’m the transmuter,” she says. “I like that word because nobody knows that word.” And yet she also knows the reimagining will be associated with her and compared to her landmark works.

“I spent all those years working on games — my own games,” Roberta says. “If I’m going to be involved, it has to be great. I’ve got a reputation to protect. Even though it’s been 20 years or so, that doesn’t mean I’m just gonna not pay attention and not do the best I can to make it great. That’s what I’m doing. That’s what Ken is doing now. We’re all in. We’ve jumped in with both feet and arms.”