Lara A. Greene keeps her antique sewing patterns in plastic tubs, stashed in the first-floor workshop of her old Victorian home so she can throw them out the window if her house goes up in flames. Greene has collected at least 10,000 patterns — possibly 20,000 — since the 1990s. And like other collectors, she is paranoid about losing them: to fire, flood, and mice or simply the indifference of people whose first instinct would be to toss them in the trash.

In 1994, Greene was a 24-year-old stitcher at the New York City Opera when she was brought along to visit Betty Williams, a costume designer and researcher with a large antique pattern collection. Old patterns are used as references by costume designers, especially when working on period pieces, and seeing Williams’ collection was formative for Greene. It began a decades-long hunt as she searched for the oldest possible examples to add to her personal archive.

“It didn’t occur to me that patterns themselves were that old. I didn’t even think about how people in the past made their garments, other than going to a tailor,” Greene says. “Once I knew for a fact that patterns that old existed, I just got lustful for them.”

Sewing patterns provide a uniquely detailed look at the lives of working-class people throughout history that clothing collections held at museums or universities seldom offer. These patterns — flimsy packets of paper covered in shapes, numbers, and symbols — guide sewists through the process of making everything from sweatpants to wedding dresses. And through most of the 20th century, before manufacturers moved production to capitalize on cheap labor abroad, sewing at home was a way to have high-quality clothing for less money.

But scholarship around patterns and home sewing is still relatively underappreciated, often dismissed as women’s work or insignificant to fashion and art. The common pattern’s ubiquitousness only adds to its disposability — patterns were cheap to purchase and finicky to preserve and were never meant to last.

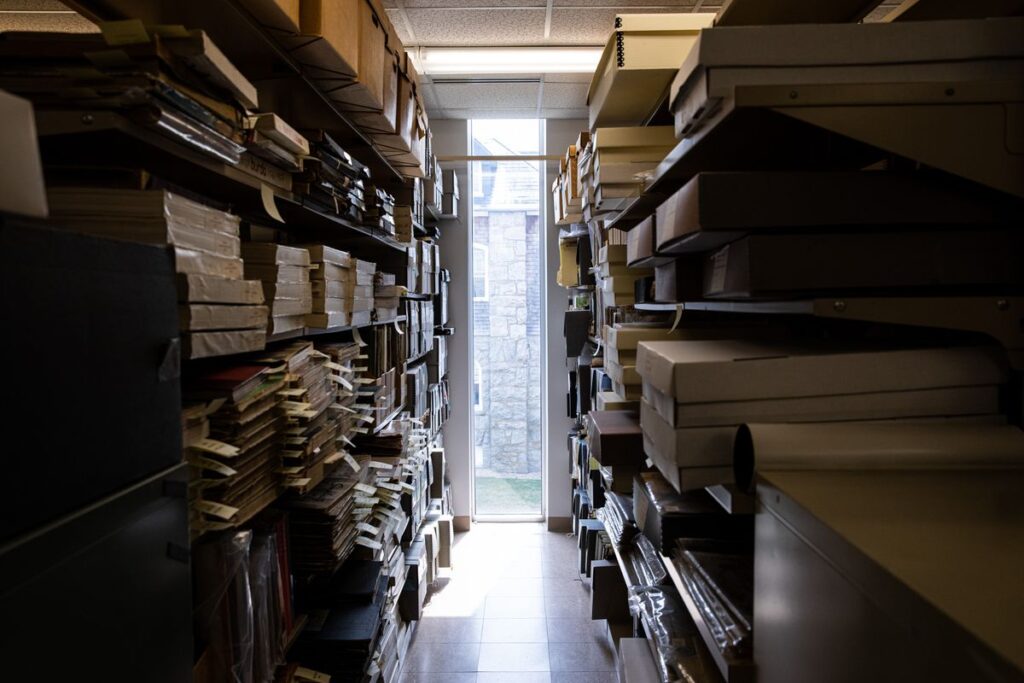

For the community of vintage sewing enthusiasts, an unassuming website maintained by the University of Rhode Island is a priceless and irreplaceable treasure. The Commercial Pattern Archive is one of the few projects in the world that safeguards these documents that are fragile, easily forgotten, and born to die. A labor of love and insistence on the part of a small team of historians, costume designers, archivists, and hobbyists, the archive began in the 1990s and includes a physical stash and digital database of English-language patterns unparalleled in its scope and depth. CoPA is home to around 56,000 physical patterns going back to the 1800s, along with books, pamphlets, journals, and other related material.

“The nightmare for most of us who collect antique patterns is that when generations inherit their mom’s or grandmother’s stuff, the paper, the ephemera, the magazines, the catalogs, the paper patterns — that’s just stuff people throw away,” Greene says.

Home sewing patterns aren’t meant to be saved for decades — they’re made to be disposable. Patterns are packaged in paper envelopes, with sizing, materials, and example garments illustrated on the sleeve. The pattern inside is printed on delicate tissue paper that might tear if a sewist looks at it the wrong way. That pattern paper is then layered atop fabric and cut along the printed lines, making reuse and resizing tedious. Once pieces are cut out of the larger sheet, it’s easy to lose them — a rogue sleeve or a missing front bodice piece — rendering the pattern incomplete.

Verge reporter Mia Sato works on a dress from a vintage pattern at a makeshift sewing station — her dining room table.

“They’re essentially ephemeral objects,” Karen Morse, acting curator of the archive, says of the patterns in the collection. “The fact that they’re even around at all is in a way a modern miracle.”

For most of the 20th century, making your own clothing was cheaper than buying off the rack, says Susan Hannel, associate professor of textiles and design at URI. Patterns were inexpensive and easily accessible, and for thousands of years, sewing was an everyday activity. And yet, most museum collections don’t include clothing from everyday, working-class backgrounds — whether that’s a work uniform or a skirt suit sewn at home using a commercial Dior pattern. For one, home-sewn garments aren’t as flashy as clothes shown on a runway or worn by the wealthy. And home sewing done by women and working-class families is generally undervalued.

“[The pattern archive] is what people dreamed about wearing, and who they were, but also just everyday stuff. You just don’t get those objects in historic costume and textiles collections,” Hannel says. “That’s lost history.”

The oldest pieces in CoPA are from 1847, when patterns in this format were first coming into being, and include baby bonnets, ruffled wraps, and robes. Though the collection is mostly women’s pieces, curators will take patterns for just about any kind of garment, from clergy robes and Halloween costumes to Cabbage Patch Kids doll clothing. The ’40s through ’70s are particularly well-represented with 7,000 to 9,000 patterns per decade, when home sewing was booming in the US.

The largest of its kind in the world, the Consumer Pattern Archive contains over 60,000 patterns dating from 1847.

Though the archive is open for in-person viewing and use, Morse says the online database is the primary way people utilize the patterns. Requests for access range from hobbyists and home sewists to designers, researchers, and curators. But unique requests illustrate the value of the collection beyond the fashion industry: Morse recalls the graphic novelist who wanted to draw characters in period-accurate clothing using the archive as a research tool. She also recently had a request from an applied mathematics professor who wanted to tag garments at key points like neckline and hem to see if there was a formula to explain changes to clothing through the decades.

When patterns are donated to CoPA, they’re first examined and compared to the existing inventory, checking for dates, a pattern number assigned by the publisher, and the type of garment. Older pattern sleeves often did not include the year of publication, and publishers regularly reused pattern numbers, so CoPA staff use supplemental materials like industry magazines, journals, and pamphlets to expertly date each piece. The front and back of patterns are scanned and uploaded to the online database, and the physical copies are placed in a protective plastic sleeve and stored in a filing cabinet in the library, where temperatures are controlled, and exposure to light is limited. Though the pattern sheets themselves are not digitized, some users have enlarged envelope scans showing outlines of garment pieces to create usable patterns.

Donations from institutions and libraries, collectors, publishers, and individuals make up CoPA’s vast catalog, believed to be the largest collection of its kind in the world. The basis of CoPA comes from Williams, the costume designer in New York, whose collection was acquired following her death. Joy Spanabel Emery, a theater professor at URI who became the leading expert on home sewing patterns, served as the curator of CoPA after retiring from teaching and eventually added her own collection as well.

Greene, the tailor and pattern collector, has used the online database for her work to research how particular garments were constructed while working on stage productions, films, and TV. Without CoPA, she wouldn’t have been able to examine the unusual pattern pieces of an evening gown from the 1930s or the complexity of an 1890s dolman, a type of outerwear resembling a shawl that wraps around the wearer’s arms. In her work for the 2013 film The Secret Life of Walter Mitty, Greene used antique patterns to outfit Ben Stiller’s character in a 1940s playsuit. Greene, who specializes in corsets, also served as a corsetier for the 2017 film The Greatest Showman and season two of the TV series Boardwalk Empire, among many other productions.

CoPA is also a popular tool for members of the Vintage Sewing Pattern Nerds Facebook group. The group’s more than 42,000 members convene to share stashes they find in attics, show off garments created using decades-old patterns, and ask questions, and CoPA is often the first stop for research in dating patterns or to find garment construction techniques that are rarely seen today. Members sort through the tens of thousands of entries, hoping to find a match to the pattern they recently came across or to dig up more information about a pattern they haven’t been able to get their hands on.

For patterns impossible to find for sale and not documented in CoPA, the search continues. One particularly sought-after pattern is Advance 2795, a 1942 women’s coverall designed by the US Department of Agriculture that’s not yet archived in CoPA. Members of the Nerds group have tried to reproduce the piece by sharing what they know about similar garments and experimenting with construction.

“I search for this every single day,” one member wrote about the coverall pattern. “I missed out on it once about 10 years ago. It was in my Etsy cart but sold when I went to check out,” says another. “Been hunting ever since!”

Though CoPA is not complete, those who use the archive say its existence at all is a marvel — there is nothing else like it in the world. Because home sewing was more accessible than expensive ready-to-wear clothing, the patterns in CoPA represent swarths of people and communities that other university or museum collections do not, says Charity Armstead, a fashion professor at Brenau University in Georgia.

“What’s preserved in museums is often the best of the best. It’s wealthy people’s clothing; it’s their best dress,” Armstead says. In contrast, CoPA’s focus on home sewing provides significant data on what rural and working-class people made, wore, and used. Armstead also notes people of color who sewed out of necessity, like Black shoppers who were denied access to fitting rooms during Jim Crow.

“We don’t know necessarily who these patterns belonged to. But we do know what groups of people historically used sewing patterns the most,” Armstead says.

The database incorporates individual donations but has also absorbed other collections, like those formerly held at the Fashion Institute of Technology. Most pattern companies did not keep consistent records of pattern designs they published or lost what they did save as companies were bought out or shuttered, Morse, the curator, says. Butterick, one of the largest publishers of patterns, was an exception; the company’s archives now live in CoPA.

“If we weren’t doing this, where would all this stuff go?” Morse says. “FIT decided that they didn’t want to maintain their pattern collection anymore. What would have happened if we didn’t take it? Would it have just gone in the dumpster?”

People who rely on CoPA can’t help but worry about the collection’s future, especially following the 2018 death of Spanabel Emery, the founding curator. Armstead, who knew Spanabel Emery and visited the collection in person, says her death was a significant loss to the field of research.

Funding, too, has caused delays. In 2017, the university shifted the database from being a paid subscription service to being open access, Morse says, which allowed more people to use it but also resulted in a loss of income that was used to pay students who worked on the collection. Money from an endowment set up by Spanabel Emery has yet to kick in, resulting in the current “fallow period.” Morse hopes to hire a dedicated coordinator and curator later this year with funds from the endowment.

Greene, the collector and tailor, is now in the process of selling off some of her thousands of sewing patterns that she no longer uses. Before Spanabel Emery died, the two were discussing how Greene’s vast collection could be integrated into CoPA, whether through donations or filling in information gaps. Mostly, Greene just wants to make sure CoPA lives on and that these irreplaceable patterns are saved and available to anyone who is drawn to them as she was.

“I definitely don’t want to be a dragon sitting on my hoard not sharing it,” she says. “I want it to be documented and useful and out there.”