Taking in Mexican artist Minerva Cuevas’s exhibition in gods we trust is like feeling your way through bits and pieces of enormous counter-narratives that retell hundreds of years of Mexican history. Like the proverbial tip of the iceberg, the offerings that Cuevas gives audiences feel so suggestive of so much more, and everything in the show seems to fit together in some unbelievably complicated way. Juxtaposing elements from ancient Indigenous cultures with 20th-century advertisements by oil conglomerates, and appropriating imagery from Mexico’s most lionized and institutionalized artists, the show pushes audiences to see beneath the surface and connect the dots.

On view at Kurimanzutto New York through 15 April, in gods we trust is a truly ambitious and wide-ranging exhibition. Cuevas framed her work as an attempt to add complexity to an all-too-simple story, bringing back many of the pieces that official accounts have left out. “I wanted to find these more complex narratives – not everything is Aztec,” said Cuevas, laughing. “We don’t know enough about these histories. I wanted to go further than this discourse of the Aztecs and the Mayas. Little by little you get these narratives of economic processes and social history.”

Cuevas is known for working on enormous surfaces and making grand statements, so it’s no surprise to find that the show’s headliner is a giant piece called The Trust – a 10ft-tall relief collage collecting 25 corporate logos, ancient Indigenous gods and symbols, national emblems, and more into a fever dream of history. Impressive and visionary, The Trust includes its own glossary to help viewers navigate the various world-ordering systems that Cuevas brings into conversation.

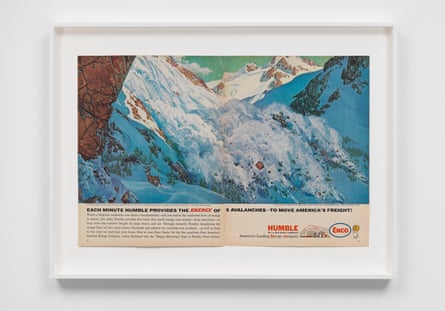

In orbit to The Trust are other collections of work exploring the same historical, political and economic narratives. For instance, a dozen reproduced vintage ads from midcentury show the now-cringeworthy ways the oil industry once positioned itself to consumers eager to tap into the possibilities of fossil fuels. There is also the artist’s curious Petro series, which stack Indigenous-themed animal heads atop oil barrels. And the collection Epopeya de un pueblo snatches away elements from Diego Rivera’s singular mural Epopeya del pueblo mexicano, reproducing them into strange groupings of stark, porcelain-white reliefs.

Self-taught, Cuevas began making video art as a teenager before eventually pursuing studies in art school in the mid-90s. At the time she felt very isolated from contemporary art trends in Mexico and relied on a DIY ethos. She started exhibiting her work in public marketplaces and forming connections with other street artists. “I was the only one with a video camera, so I was helping other artists,” she said. “I would record their shows. We were helping each other and it was very low-key.”

Cuevas got drawn into the anti-globalization movement and became fascinated with the Zapatistas, who emerged with a bang on 1 January 1994 in opposition to the institution of the North American Free Trade Agreement. She recalled that these movements reflected her own beliefs, as she had lost faith in the governmental institutions in Mexico. “The first logo I modified was related to the government, not a corporation. It had to do with the national lottery – using the statistics of poverty in connection with the enormous monetary prize offered by the lottery.”

Throughout her career, Cuevas has bristled at the term “activist”, seeing what she does as something wholly different – art. True to form, in gods we trust doesn’t feel like it’s trying to convey a certain message about colonialism or environmental degradation as much as it’s trying to pull so many disparate pieces together into a thesis about what has happened in Mexico from pre-Hispanic times to today. “I’m just bringing elements together, like a cultural experiment. Let’s put these things together and see what happens. It’s not me who’s criticizing the oil companies. I tend to avoid moral statements – I think moral statements are the worst things to connect socially with people,” she said.

Cuevas sees her work with logos as related to “archaeology”, 21st-century corporate branding existing on a spectrum that also includes Indigenous gods, national emblems and even stock exchange graphics. “I wanted to use logos as a way to access people’s image banks, as a way to connect with our visual language,” she said. “As I looked more into logos, I found that there were commonalities in their production – certain national resources appear again and again, animals, various colors.”

For Cuevas, the works she produced for in gods we trust also marked a personal turning point as an artist – long eschewing artists like Diego Rivera for their association with power centers in Mexican culture, she began to see this art in a different light, realizing that his centrality and connections to the pre-Hispanic culture posed an opportunity. “The younger generations have lost interest in Rivera’s historical movement because it’s so institutionalized,” Cuevas said. “Creating this art, this was the first time I could relate to the cultural history in Mexico.” For in gods we trust, Curvas pulled out a series of motifs from Rivera’s magisterial mural Epopeya del pueblo mexicano, completely decontextualizing these elements and forming them into series of all-white assemblages. In this way, she hints at how the narratives surrounding Mexico’s Indigenous peoples and its enormous natural resources have been pulled apart and reformed so many times.

The show also features a series of reproduced vintage advertisements from oil corporations. For today’s audiences, many of the ads’ text reads like extremely cynical parody – for instance, one ad exuberantly proclaims “Each Day Humble [Oil] Supplies Enough Energy to Melt 7 Million Tons of Glacier!” The ads offer implicit commentary on how the image of oil extraction has transformed in the past 70 years, even as it remains a central part of the Mexican economy and its ties to the larger world.

“Visitors have been really curious about the vintage ads,” said Cuevas. “They find it unbelievable that they haven’t been changed in any way! You can see there the history of the oil industry’s interests – in the 40s it’s connected to war, and racism played a big part in politics and the economy; in the 50s car culture was the main interest; later in the 60s they were very much connected to the natural elements and landscape.”

As much as this is a show about Mexico and its history, it sits very well in a New York gallery. In fact, Cuevas excitedly pointed out the exhibition’s many resonances with New York’s history, including the connection between Rivera and the Rockefellers, who first commissioned the painter’s mural at the RCA Building at Rockefeller Center, but later rejected it for being communist propaganda. There are many other less-known connections as well: for instance Cuevas told me that Chase Bank was integral in planning the city’s water infrastructure. And there were also smaller, more coincidental connections. “One of my oil barrels has a torch on it – I ended up using that torch as a part of the main mural, and someone pointed out that it connected to the Statue of Liberty,” she said. “It was really a nice coincidence. The pieces I chose for New York are very specific to that context. I’m responding to the city.”