Of the hundreds of galleries in London, none has been given over exclusively to the growing and vibrant market for African photography. Until now, that is.

Doyle Wham is the creation of two young Londoners who are eschewing Britain’s “elite” art scene to open what they say is the country’s first ever gallery dedicated exclusively to African photographers.

“We were aware of so many amazing photographers who were Africa-based but who weren’t being exhibited or even noticed,” says Imme Dattenberg-Doyle, 27, a graduate of the Royal College of Art in London.

She and her friend, Sofia Carreira-Wham, 28, a museums and heritage scholar, have opened Doyle Wham as a new permanent gallery in a converted warehouse in London’s Shoreditch.

The founders started out offering pop-ups and one-off exhibitions of African photography – “not safari shots by random people, but African photographs by African people!” says Carreira-Wham.

“It sounds niche, but, for us, it wasn’t really like that,” she says. “We’d been sending each other incredible African photographers back and forth for some time via social media, and we’d spent a lot of time going to exhibitions, but we didn’t see any of this exciting talent being shown.”

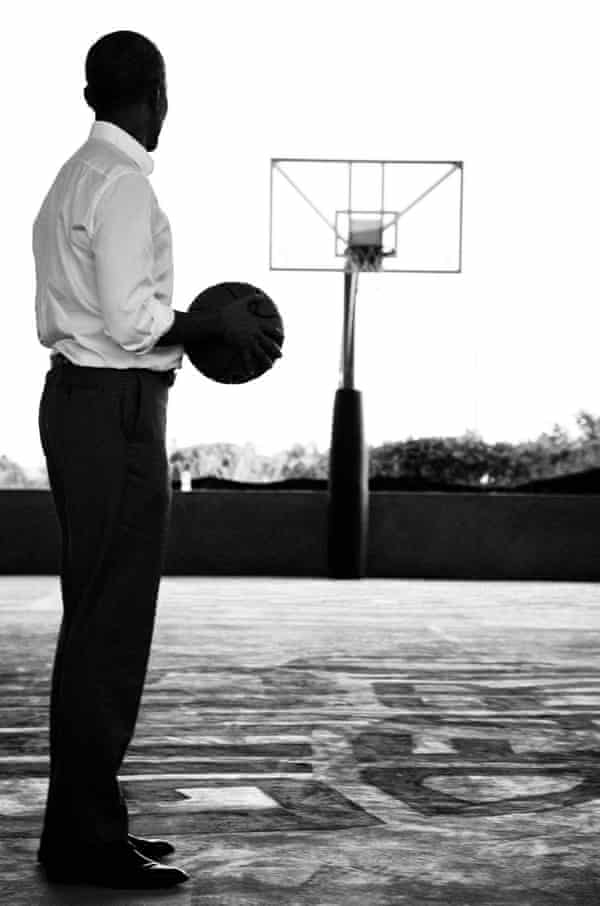

That talent begins with South Africa’s Trevor Stuurman, the first big solo show at Doyle Wham. His bold, highly stylised images are of black men and women in poses that the artist says are about elevating and celebrating African people, and taking back the narrative so that Africans, like him, tell “the African story”, rather than having it imposed on them by others.

Despite Stuurman’s immense success in his home country, with subjects including Barack Obama, Naomi Campbell and Beyoncé, the 29-year-old’s photography has never featured in a gallery in Britain.

Speaking to the Observer from his home in Johannesburg, Stuurman says the gallery is a much-needed platform for African artists.

“I feel like so much was stolen from Africa, and it’s about reclaiming that. That’s why I think photography is such a powerful medium – it allows us to retell the story and show what [the continent] looks like now – to cultivate a better understanding of what Africa is,” he says.

Stuurman grew up in a small mining town five hours drive from Johannesburg, and started taking pictures when he was 14, not with a conventional camera but using a cheap mobile phone, he says. (Stuurman’s family had little money, and his father died when he was still at high school.)

He took shots of his friends, imitating poses they’d seen in glossy magazines at the local grocery store. After leaving school, he took an SLR camera on to the streets of Cape Town and snapped pictures of everyday people. That brought him his big break, winning a competition with Elle magazine and a trip to London – his first time outside South Africa.

At 19, he found himself on the front row of a Burberry show. It was surreal, he says. “These figures I’d seen in the magazines were literally right in front of me. It was a world I’d always looked at as a fantasy – and there I was, part of it.”

A decade on, Stuurman has been credited with helping change the visual narrative of contemporary Africa (Beyoncé picked him to work on styling and costume design for her 2020 film Black Is King).

“Being African is my superpower. I want to use it to capture African images that don’t exist on Google,” he says.

This idea of casting new light on Africa, instead of focusing on the continent’s wildlife, poverty or charity, is also at the core of Doyle Wham, says Carreira-Wham.

Later this year, they will exhibit work by the Gabonese photographer Yanis Davy Guibinga, Nigeria’s Morgan Otagburuagu and Angèle Etoundi Essamba from Cameroon – artists who each have incredible and authentic stories to tell through their work, she says, but who are so far unknown outside their own countries.

Doyle Wham’s founders also hope to challenge snobbery and the perceived low value of African photography in Britain’s galleries and auction houses.

“People (especially men) come up to us all the time and say things like, ‘but collectors don’t want aluminium frames’ – and ‘there’s no value in African photography’,” Dattenburg-Doyle says.

“And we’re like, OK, we’ll figure that out for ourselves, thanks.”

They are trying to brush aside this elitism, they say, and come up with their own ideas – like “snaps and schnapps nights” every Thursday. Not one for the purists, perhaps, but anything to get people – especially younger people – through the door of the gallery.

Trevor Stuurman: Life Through the Lens runs from 13 May to 2 July at Doyle Wham in London