When television goes to college, it’s usually to focus on the students, with their youth, dewy skin and lust for life undimmed by time, experience or perspective. These shows offer a hit of fantasy nostalgia for older viewers and a flattering mirror for younger ones. They’re sexy by nature.

Stories that focus on professors and administrators are a different breed. (The 2021 Netflix series “The Chair,” with Sandra Oh, was a rare recent example, and it died after a season.) If often as childish as their most difficult students, these characters may carry the added weight of moral exhaustion, aging bodies and/or minds, spouses or ex-spouses, and children; their days are mired in bureaucratic folderol, intra- and interdepartmental competition amid shrinking budgets, and the pressure of just holding on to a job. Not so sexy!

Even so, bookshelves’ worth of literary works have been set in that milieu. Many writers have not only been to college but have also worked in them, and age tends to play better on the page than coming off an 80-inch, 4-K flat screen.

One such book, Richard Russo’s 1998 institutional comic novel “Straight Man,” set in a third-tier college in a distressed western Pennsylvania town, has become the series “Lucky Hank,” premiering Sunday on AMC.

Bob Odenkirk plays William Henry Devereaux Jr., a professor of writing and chair of the Railton College English department. The author, years before, of a well reviewed but unsuccessful novel, he’s the estranged son of a literary critic so esteemed his retirement is front-page news. He’s married to Lily (Mireille Enos) — reason enough to call Hank lucky — a high school administrator whose patience he often seems on the verge of exhausting; they have a grown married daughter, Julie (Olivia Scott Welch), who is ever in need of money. Hank is also having trouble urinating and is convinced, in spite of his doctor, that he has a kidney stone because his father had them — which, apart from a name, may be all that he’s inherited from him.

Creators Paul Lieberstein and Aaron Zelman, who co-wrote the two episodes available to review (both directed by Peter Farrelly), have turned up the heat on Hank. In the novel, which is less the story of a midlife crisis than midlife stasis, he comes across mostly as amused or bemused. Here he’s more dyspeptic, cynical, unsatisfied, insecure, prone to panic and driven by insecurities. He’s avowedly miserable. (Hank to Lily: “Who isn’t miserable? Being an adult is 80% misery.” Lily: “I think you’re at 80. The rest of us hover at around 30 to 40.”) That he hasn’t written a second novel — the failure of nerve also assigned to Jay Duplass’ character in “The Chair” — is much more of an issue in the series. While novel-Hank has come to terms with the possibility he’s just a one-book writer, series-Hank is haunted by it.

All these qualities lead early on to an outburst in class, prompted by a particularly trying student, the self-admiring Bartow (Jackson Kelly), who is quite sure that his work is beyond criticism. Demanding a stronger reaction from Hank, he gets it.

“The fact that you’re here means that you didn’t try very hard in high school or for whatever reason you showed very little promise. And even if your presence in this middling college in this sad forgotten town was some bizarre anomaly and you do have the promise of genius, which I’ll bet a kidney that you don’t, it will never surface. I am not a good enough writer or writing teacher to bring it out of you. But how do I know that? Because I too am here. At Railton College, mediocrity’s capital.”

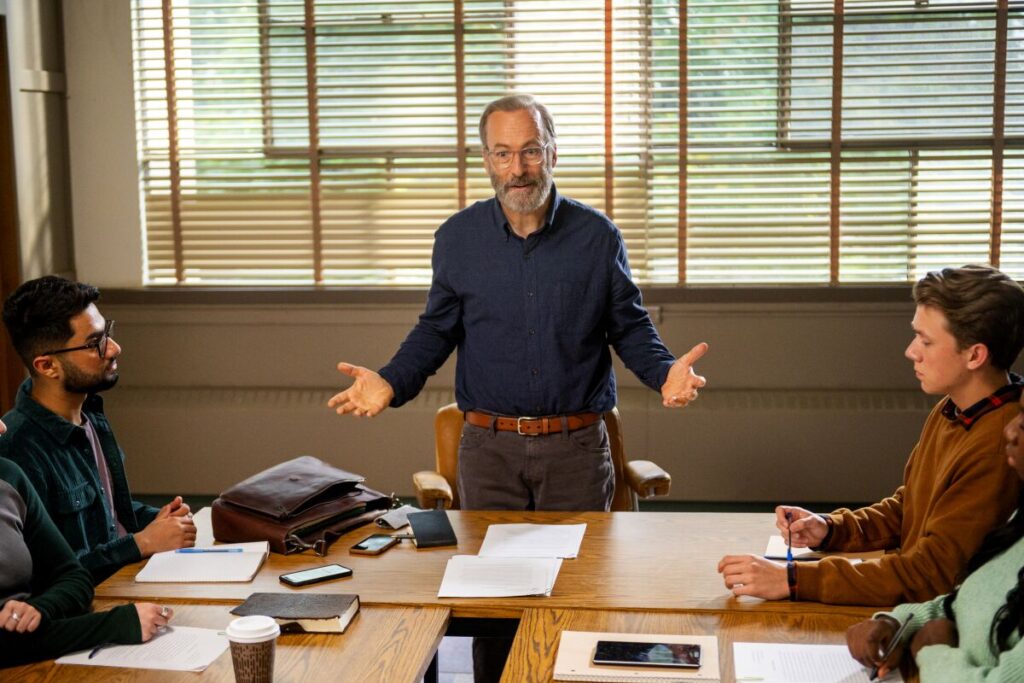

Odenkirk as a cantankerous writing professor at the fictional Railton College.

(Sergei Bachlakov / AMC)

Having felt himself demeaned by Hank, whose rant winds up published in the campus newspaper to general chagrin, Bartow — who stands for a certain sort of entitled sensitivity — will not be content to accept his apology but insists it also be published in the campus newspaper. He is, seemingly, a nemesis in the making.

Surrounding Hank are characters as pointedly individual and colorful and as antagonistic as the cast of any workplace sitcom. In the English department are Paul (Cedric Yarbrough), who is at war with Gracie (Suzanne Cryer); Teddy (Arthur Keng) and June (Alvina August), who are married; Finny (Haig Sutherland), pretentious; Billie (Nancy Robertson), drunk; and Emma (Shannon DeVido), who is, if anything, more sardonic than Hank. Above them is Jacob (Oscar Nuñez), the dean, who goes out of his way to be accommodating but is also threatening budget cuts that make the professors feel that their jobs might be on the line. (Hank, who regards these threats as seasonal and empty, is more sanguine on this account.) Diedrich Bader plays Tony, Hank’s friend and racquetball partner, who also works at the college.

With only two episodes available to review, it’s hard to tell just how much of “Straight Man” will find its way into “Lucky Hank.” (The opening shot, as Hank contemplates the college duck pond, suggests that at least one major incident from the book will repeat in the series.) The novel is eventful without being especially plot heavy, and in its early stages the show comes on less like a strict translation of Russo’s novel than the foundation of a workplace that might wander any old way and continue for years, whereas the book takes place over a week.

Indeed, the first two episodes contain myriad original scenes and plotlines, most notably a visit to the campus from George Saunders, a real author played here by the actor Brian Huskey, with whom Hank started out but who has far outpaced him. And though they have imported Russo’s characters — with some alterations — Lieberstein and Zelman have not used much, if any, of his dialogue and written their own jokes for Hank, some of them better than the book’s.

Odenkirk, who started out as a comedian, is a fine choice for a character whose main conversational mode, and way of dealing with the world, is the dry wisecrack. (These either tend to be ignored or to escalate a situation — no one ever laughs.) A more or less charming antihero once again — his Saul Goodman was all that kept me watching “Breaking Bad” — who may or may not become more hero than anti with time, he exerts a kind of authority even as he avoids responsibility.

Enos, a soulful presence wherever she turns up — “The Killing” is where many of us would have met her — is so sympathetic that, if there’s something out of tune in the opening episodes, it’s that you can’t quite see how Lily and Hank have stayed married. One greets a scene in which they walk holding hands with relief and hopes for more of that, not that dark comedies are in the business of satisfying those hopes.

There’s something about the series that feels both quaint and timely, given current debates about the worth of college and the marketability of an English degree. Nevertheless, people still attend college or work in one, and write books or want to. And though “Straight Man” was written in a world before media was social and when cancellation was a word applied only to the likes of TV shows and restaurant reservations, its social dynamics and cultural concerns are still very much alive. “Lucky Hank” intensifies them to entertaining effect.

‘Lucky Hank’

Where: AMC

When: 9 p.m. Sundays

Rated: TV-14 (may not be suitable for children younger than 14)