“Saltburn” director Emerald Fennell had one directive for her cinematographer: “It needs to feel like a vampire movie.”

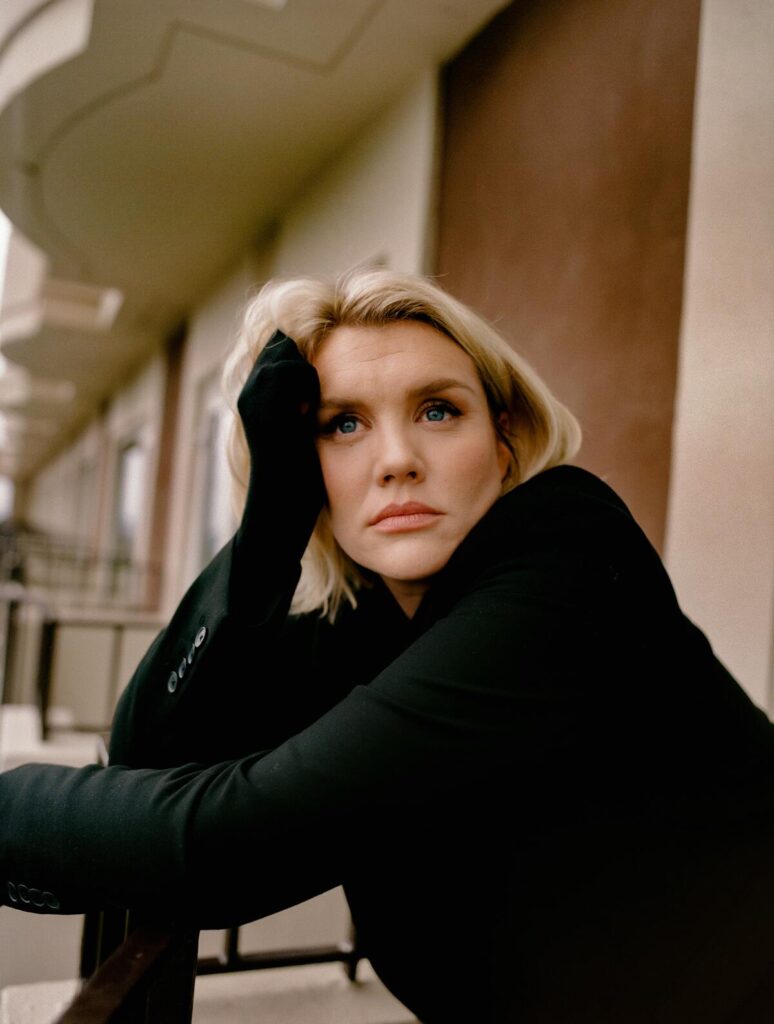

(Tracy Nguyen / For The Times)

“Saltburn,” writer-director Emerald Fennell’s second feature, is about a lot of things: class, desire unquenched, obsession and a summer vacation at a sprawling upper-crust estate where things are certain to fall apart. And when Fennell met with Linus Sandgren, her gifted cinematographer, she told him exactly how she wanted “Saltburn” to look. “I said, ‘It needs to feel like a vampire movie, be incredibly sexy and we need to shoot the house like a fetish object,’” recalls Fennell.

“Saltburn” is the dark tale of a friendship between a cowed-looking Oxford scholarship student, Oliver (Barry Keoghan), and his effortlessly gorgeous aristocrat classmate, Felix (Jacob Elordi), with Fennell admittedly borrowing from the best of the English country house thriller genre. “Tropes are great,” she says. “It’s a shorthand. They create a world, they put you in the frame of mind — and then you can slowly undermine it.”

You’re also a working actor. How does that affect the sort of conversations you have when directing?

The moment [Oliver] meets Felix is quite a good one to talk about, because it’s no longer about Oliver and Felix. The game of it is, “You guys have worked together for seven weeks and you know each other really well. So what can you do?” So I said to Jacob, “Felix is the hero of a romantic comedy. I want to see you take Barry down with your charisma. Barry should not be able to remember his lines because your charisma is so potent. The motivation here is to get Barry to fall in love with you,” and then you get Bambi eyes. And Barry afterwards was like, [breathlessly] “Holy s—.”

From left, Alison Oliver, Jacob Elordi and Barry Keoghan in “Saltburn.”

(Chiabella James / Prime Video)

Because of “Saltburn’s” themes of power and privilege, were you tempted to treat the cast members differently?

Some people love working that way. But I want to rely on the fact that [I have cast] actors who are so good they’re going to get there themselves. Some actors like [being] immersive. It’s a completely valid process. But I feel that I’ll get the very best out of people when they know I’m going to be completely honest with them. That means when I love it, they know I love it emphatically. And if I don’t, I can really kindly but clearly say, “That didn’t work. I didn’t feel that.”

What was it like to first set eyes on the 127-room mansion in Northamptonshire that’s “Saltburn’s” main location?

It was terrifying, because I was like, “If they don’t let us film here, I’m going to be heartbroken.” It had all the things I wanted. The house itself had to be alluring, beautiful, different, unique. But it [also] had to feel like a place where a family lived, not a museum or a hotel. You’ve got a chapel, five dining rooms, and not one, but two, cantilevered staircases. The house, like the people in the movie, had to be so seductive that even if we know better, the moment you see it, you think, “I want in.”

What I love is that [these] houses are built for voyeurism. There are mirrors everywhere, sometimes multiple hidden doors. Staff only come in once the family leave, and then they clear everything away.

(Tracy Nguyen / For The Times)

Is it true that Paul Rhys, who plays the estate’s smirking, all-seeing butler, was allowed to sleep at the house?

The first conversation I had with Paul, I said to him, “You are the house.” And he knew I didn’t mean it metaphorically. He is the house. Paul is kind of gently Method. So it made total sense for him to stay there.

You have a handful of eating scenes — describe shooting the elegant guest-filled dinner party.

Because the whole scene was candlelit à la “Barry Lyndon” and there were so many people in the room, the walls started to sweat and the paintings started to warp. It’s testament to how amazing the people who worked in the house were. They said, “Can you shoot the rest of the scene in 20 minutes?” And I said, “I can,” and they let us continue. And that’s the thing. It’s always about trust and relationships. You cannot expect people to go the extra mile unless you’ve earned their trust and respect.

Your set on “Promising Young Woman” was famously female driven. Was it different on “Saltburn”?

Actually, our crew was over 50% women, so we were more women than men. We are and may still be the first film of our budget level and above in England that has ever had that high a statistic. It’s incredibly important to take all of that into consideration. We have humane hours so that people can get home, put their kids to bed or read them a story; we have all that stuff.

What else makes a film production run well?

We don’t have any nice trailers. Everyone has exactly the same kind of crap two-way. We have a communal greenroom and makeup room on set always. If the actors have any downtime, they go and sit in the greenroom, whether they’re the lead or they’ve got one line. Everyone eats together, cast and crew. So much of the structure of this industry is designed to make people feel alone, to make them feel they’re in competition with each other: Who’s got the biggest trailer? I just don’t think that’s a way to make interesting work.