She is a 66-year-old self-proclaimed all-American Jewish lesbian folk singer and cardboard cobbler, a queer punk icon who forged her feminist voice before most riot grrrls were born.

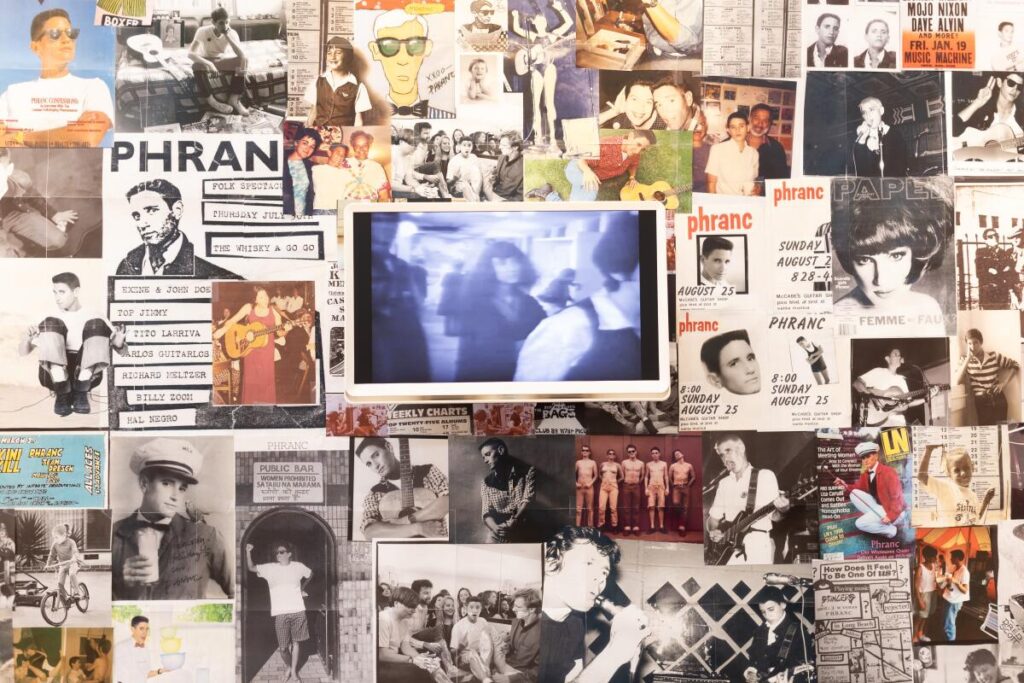

“Queercore was a dream for me because it was what I wanted when I was 20,” Phranc says, looking over five decades of notebooks, fliers, tour lanyards and promotional items created by Island Records to promote her first major-label release in 1989. Some of Phranc’s foundations surround her, including a paper sculpture memorializing the Slash magazine T-shirt that Phranc wore in the 1970s, and the drawings she made as a teenager working at the Woman’s Building, the Los Angeles landmark hailed as the nation’s first female-owned and -operated community center for feminist art and education. It’s all illuminated by the glow of 8mm home movies her parents shot in the 1960s.

Before signing to Island, touring the world with the Smiths or gracing stages in drag as Hot August Phranc, she surfed, interned at the Lesbian Tide magazine and played in early Los Angeles punk bands such as Nervous Gender, Catholic Discipline and Castration Squad at places like Club 88 and the Hong Kong Café. Phranc changed her sound and hosted folk spectaculars at the Whisky, performing “Take Off Your Swastika” acoustic in the style of the lesbian and radical folk singers who inspired her before punk. Phranc got her trademark flat top (artist Albert Cornejo is still her barber) and started making cardboard sculptures of food, selling her work to make rent on an East Hollywood apartment.

“The Butch Closet,” Phranc’s experimental retrospective at Craig Krull Gallery in Santa Monica, feels like a memoir. From reproductions of the dress she never wanted to wear to the boots that have become a part of her, the pieces in the show illustrate her life lived in clothing and music, set against important moments in L.A. history. The exhibition tracks her evolution from a young girl to an old butch through drawing, sculpture, fiber art, archival material, ephemera, music and other performance. Her care for community, sense of humor and knack for bringing people together are palpable. This conversation has been edited for length.

Old photos and ephemera from “The Butch Closet,” queer folk punk star Phranc’s show at Craig Krull Gallery in Santa Monica.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

I’ve heard that you got into Nervous Gender because you looked hot hanging around outside of a club in L.A. Is that true?

Well, it wasn’t outside of a club! It was an Avengers and Mutants show in Vermont. I was at the show, not knowing a soul, in a suit and tie, just trying to look cool, leaning up against the wall. Edward Stapleton came up to me and said, “Wanna to be in band?” And I was like, “Yeah, I play guitar!” I had this whole background, but it had nothing to do with it. I fit the bill, and I was off to the races.

How incredible because Nervous Gender was the queerest band in town, three gay men with incredibly different visions than I had. I played guitar a little, but mainly it was synthesizers and I’d never seen a synthesizer in my life! Gerardo Velázquez had such vision. I think I fit the vision, but I could never sing those songs to Gerardo’s liking; he was very particular. “My Mommy’s Chest” probably came the closest. Gerardo died of AIDS in 1992; I wish he lived to see what’s happening now in music.

So many queer musicians were a part of the early L.A. punk scene. It’s wild that the feminist art world and the queer world didn’t explicitly overlap with punk until much later.

Nobody had come together yet. But as individuals, if you were queer, that early 1970s L.A. punk community was a fertile place to be.

Nervous Gender was part of a benefit for the Woman’s Building. All I could see was the similarities between punk and feminism, how much we had in common, you know? We were oppressed by the same forces, I thought we should be one. This benefit — they just pulled the plug on the band! We just could not see eye to eye.

Can we talk about those early queer and feminist communities that helped you to develop as an artist at such a young age?

Feminist art is where I developed my identity, my foundation and my perspectives, which are continually changing. I didn’t just come out as a dyke onstage in punk, I’d already been at the Woman’s Building and part of the lesbian feminist scene in West L.A. I was the little junior dyke at Lesbian Tide with Jeanne Córdova, who had a huge influence on me.

There was a newsstand across from Canter’s, and there was a copy of the Lesbian Tide. On the back was a list of queer and lesbian places, and women’s places. There was a lesbian feminist drop-in rap group, in Santa Monica. I told my mom I was going to the library, and I rode my bike there. I stumbled in and I sat down in the circle of women having a meeting, and they asked, “Why are you here?” I said, “because I like chicks.” And they were like, “Peep peep peep!” Finally, they said, women are not chicks. That was my first consciousness-raising lesson.

These women were so kind to me, they took me in. My whole story is based on community. Community raised me.

An experimental retrospective of Phranc’s career include her paper art creations and other reflections of her life in L.A.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

When did visual art become central to your creative practice?

I’ve always made artwork, since I was a kid. Always on cardboard. When [the album] “Folksinger” came out, I started touring with the Smiths and did shows with Violent Femmes. when “Positively Phranc” came out, I toured with Morrissey. Right when things were starting to peak, my brother was murdered, and everything stopped for me. My brother was a very kind and generous person. When you lose a family member, it affects everybody. I just stopped, I didn’t want to be in front of anybody or perform anymore.

Jill Burnham at 18th Street Arts Complex in Santa Monica said, “We have this space opening, do you think you might want it?” It was a dark room. I painted it and started making my cardboard work. I made a lot of cardboard food when I lived on Normal Avenue because I was always hungry. I painted food, then I’d have sales the day the rent was due.

Why cardboard?

Cardboard is great because it’s free. You can find it in the alley. You don’t need anything. You don’t have to have money to make art. I learned to sew eventually so the work started transforming.

(Myung J. Chun/Los Angeles Times)

Why call your show “The Butch Closet”?

I’m calling it a closet, not just for the metaphor of the closet, but also because the closet is a place where you keep things, where things can grow, where you can put yourself together. I’m using it to tell the story of how I grew up to be who I am today from birth to punk rock, and a little beyond there.

I have re-created mainly objects of clothing that were significant to me growing up. It starts with my baby quilt made of paper and cardboard. I have a Slash T-shirt, my favorite jacket from when I was 5, my Lamb Chop Halloween costume. Re-creations of significant pieces of clothing that tell my story.

Why is clothing central to your work?

It’s the constant and so significant in claiming identity. Growing up I had to wear a dress because of dress codes. That didn’t change until seventh grade. They let you wear pants; it was torture up until then. It was a struggle at home. I see so much reflection in that today. Why can’t we all feel good about who we are, and present ourselves in the way that feels the best to us without restrictions on who we can be and how we can look?

When you talk about being queer, coming out, cutting or growing your hair, wearing clothing that makes you feel good and strong and like you are who you are — that’s why clothing.

What does the word ”butch” mean to you?

I’ve had an interesting relationship with the word “butch” over time because when I came out, it was the beginning of the lesbian feminist movement. There wasn’t appreciation at the time for the old gay community, especially the butch femme community, where many butches passed as men to save their lives and be who they were with their partners. You’d see the older butch femme couples in the bars with their ties and big hair. And some of the older dykes would say, “Oh, you’re such a baby butch” as a compliment, and I would be very defensive. I’ve come to appreciate through the years that butch identity is something to be honored and cherished. Our history is something to be loved and appreciated. I’ve evolved, as I have in many ways of my life, I’m proud to be butch today, I love it. You can call me butch.

(Myung J. Chun/Los Angeles Times)

Butch has always been a part of the lesbian and the trans community. It’s a both/and, and people could be on many different places of that spectrum.

Yeah! And now it’s cool to be butch!

What becomes illuminated for you in the process of translating something from everyday life into this other medium?

I’ve felt so strongly about this little plaid jacket from my childhood, I’ve wanted to make it forever. You’ll see in the home movies. I’m wearing it wherever I go. It was a long making because it’s plaid. The way I make my paper is I roll out a giant roll of craft paper, and then I paint the paper to look like fabric. And then I cut and sew it like it’s a piece of clothing. Each piece is painted and created and then cut as if it was fabric.

Making plaid is such a meditative process, every brushstroke of making that plaid, the memory of wearing the jacket, the memories that come up in the creation, that is all the energy that’s put into the piece. Making that jacket and painting that plaid was an intense process. And when I see it made, it just fills me up. I’m hoping all that feeling is something that people feel when they see it.

Phranc’s paper-art creations include a replica of her baby blanket.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

This genre of working with your younger self is becoming a beautiful queer style of storytelling. Can you talk about what it’s been like to look back on and collaborate with your younger self through this project?

It’s interesting and it’s weird. You look back and you see things that you didn’t remember. Last night, I was looking at a video from 1975. I’m singing at the opening of the Woman’s Building and there’s Judy Chicago, and Gloria Steinem, and I’m on the top of this ladder, with my tie, and I look around, and I forgot my grandparents were there!

I left home when I was 16 because I couldn’t be a dyke at home. When I became a little bit more successful, my parents were pretty supportive from that point on. But before those years, they documented everything. My mom would sign me up for Parks and Recreation, just like Billie Jean King. There’s footage of me skateboarding, learning to ride a bike, surfing. I had such the 1950s 8mm childhood. I didn’t realize all the good stuff that I had when I was a kid.

Why did you make “The Butch Closet” a retrospective?

I could have had a show of new work because I’ve been focused on making these significant pieces for the last three years. I could write a bunch of new songs. But it’s the same song. How old is “Dress Code”? That song came out in 1990. What I do and have done onstage the last 30 plus years is storytelling. The songs are storytellers, and so are the objects in my show. That’s the constant between my visual art and my music. They’re both on a parallel track of storytelling. “The Butch Closet” tells a story, in music, with visual art, and archival memorabilia, the story of becoming.

It’s special that I’m here to tell the story. As a young queer coming out, I had all the struggles with self-worth and suicide that many of us have. Coming out, having a community waiting for me at that women’s center saved my life. I’m lucky to be here to do it. There’s no better time for me to include as much of my story and process into the show as possible.

“The Butch Closet” at Craig Krull Gallery.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

‘The Butch Closet’

Where: Craig Krull Gallery, Bergamot Station, 2525 Michigan Ave. Suite B3, Santa Monica

When: Through Dec. 2. Reception 4-6 p.m. Saturday

Info: (310) 828-6410, www.craigkrullgallery.com