Willem Dafoe knew the script for Yorgos Lanthimos’ “Poor Things” was different the moment he read it. It was teeming with big themes — identity, social convention, hubris and human attachment. It was also fantastical and often funny. But Dafoe, a four-time Oscar nominee known for his soulful, cerebral presence, has been doing this long enough to know the page is just the starting block. “Scripts have to be put on their feet,” he says in a video interview from his home in Rome. And Dafoe was ready to help “Poor Things” stand up on the screen.

“It’s about collaboration,” he says. “It’s about melting into the thing, becoming the thing, not having it be about you, but also having it be intensely personal. I think it’s a chance to lose yourself in something bigger. That means these people coming together to tell a story or express a world or express a hope. And I’m down with that. That’s what makes it fun to get up in the morning.”

Dafoe is primed to score his fifth nomination for his performance as Dr. Godwin Baxter, a Victorian scientist and surgeon bearing scars inside and out. Baxter’s favorite creation is Bella (Emma Stone), a young woman who survived a suicide attempt only to begin a new life in the strangest of ways: Baxter, called God by those around him, has given her the brain of her unborn child. Paternal, protective, by turns gruff and caring, and more or less insane, the good doctor is the latest take on Victor Frankenstein, the mad scientist of Mary Shelley’s archetypal horror novel. When Bella leaves to sow some wild oats with a caddish lawyer (Mark Ruffalo), Baxter pines for his creation even as he knows she must become her own human being.

When Dafoe told an actor friend he would be working with Lanthimos, a master of deadpan absurdity, he was warned: “Oh, God, he’s going to not want you to act at all.” The Greek filmmaker built a name for a sort of anti-acting style, an almost Brechtian distancing. But his more recent films, including “The Favourite” (the 2018 drama for which Olivia Colman won a lead actress Oscar), have expanded the performance palette.

The actor saw the potential for fun in the “Poor Things” script by Tony McNamara. “It’s such a complex world,” he says. “The relationships are on paper, but you don’t know the depth of them until you play those scenes. With a director like Yorgos, it’s about being ready for anything and being game and taking on the world, taking on what’s around you from watching.”

Dafoe, a Wisconsin native, has made a career from being watchful and game, starting with his days on stage as a founding member of the groundbreaking experimental New York theater company the Wooster Group. He was drawn to avant-garde playwrights and such directors as Richard Foreman and Robert Wilson, who taught him the importance of being present for whatever might happen.

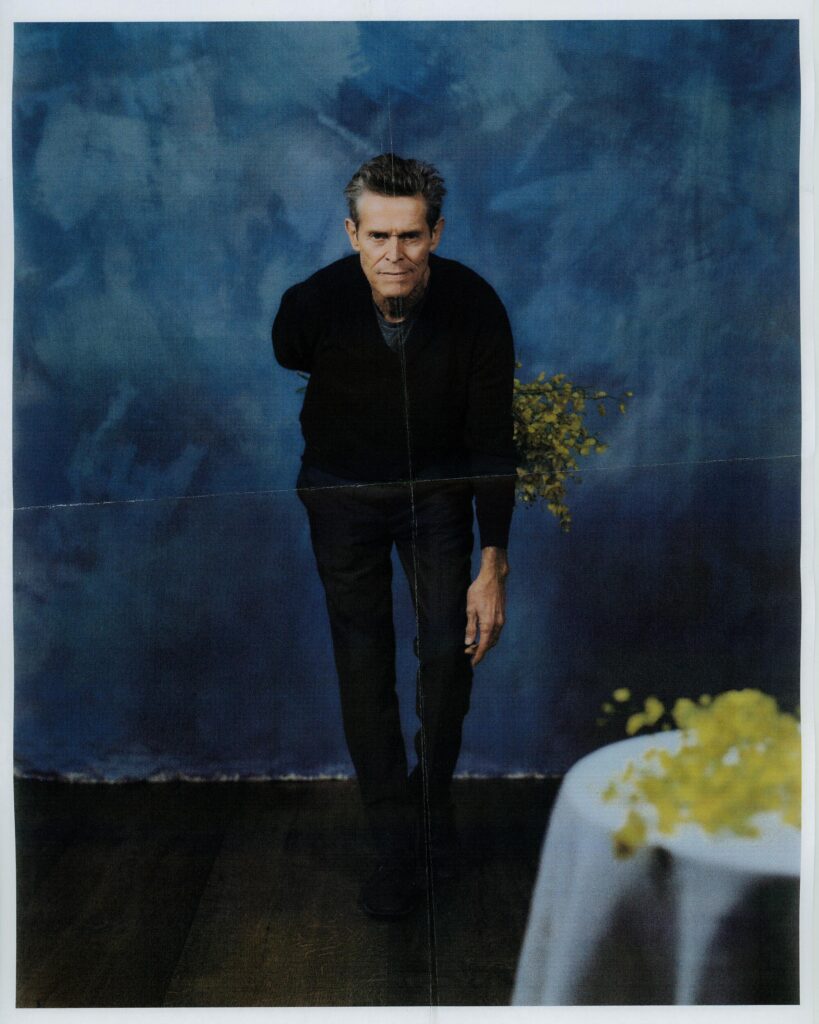

Willem Dafoe plays the scarred Dr. Godwin Baxter in “Poor Things.”

(Atsushi Nishijima / Searchlight Pictures)

“All the theater work really made me who I am as a film actor,” he says. “I think the principal thing is the idea of doing. It’s about the quality of being there. Receptivity to what is around you is so important.”

His roots also taught him that the work comes first, before making a buck or earning fame (though he isn’t averse to hitching himself to a quality franchise; his Green Goblin added considerable color to Sam Raimi’s “Spider-Man” movies). When you see a Dafoe performance, you’re seeing pure dedication to and joy in craft. The accolades come, but they’re never the guiding force.

He traces these priorities directly back to his Wooster days.

“We felt like a bunch of kids that were doing this for now; we’d do something else later,” he says. “That was a luxury, because it taught you the beauty of really doing this for this, not doing this to get that. It wasn’t about career. It wasn’t about you. It was about making something with people. When you’re with good people and you’re in that collaborative spirit, that’s when the best things happen.”

But his commitment to honesty also keeps him from downplaying the importance of awards. He knows he can give the work precedence and still savor recognition, especially when the recognition draws viewers to projects he felt passionate enough to make in the first place. He knows what business he’s in. And he knows it is, indeed, a business.

“Awards help those films get seen,” he says. “And when you make a movie that you think is worthwhile and you feel deeply about it, maybe it’s silly, but it breaks your heart when it doesn’t get good distribution. So I like anything that helps a movie get seen and also helps you.”

What does he feel most proud of in his long career? Dafoe initially demurs. “You don’t want to be proud of anything, because then you have to protect it,” he says. “But this I don’t have to protect: I still love doing what I do, because it’s always different. For me, it always gets deeper. It teaches me things. It’s a beautiful job to have. I’m very lucky. You don’t want to lean on that too much, because then it’s like someone talking about having a religion or something — I have this, you don’t. But I’m proud of the fact that I still get very excited when I go to work.”