Shared from www.wired.com.

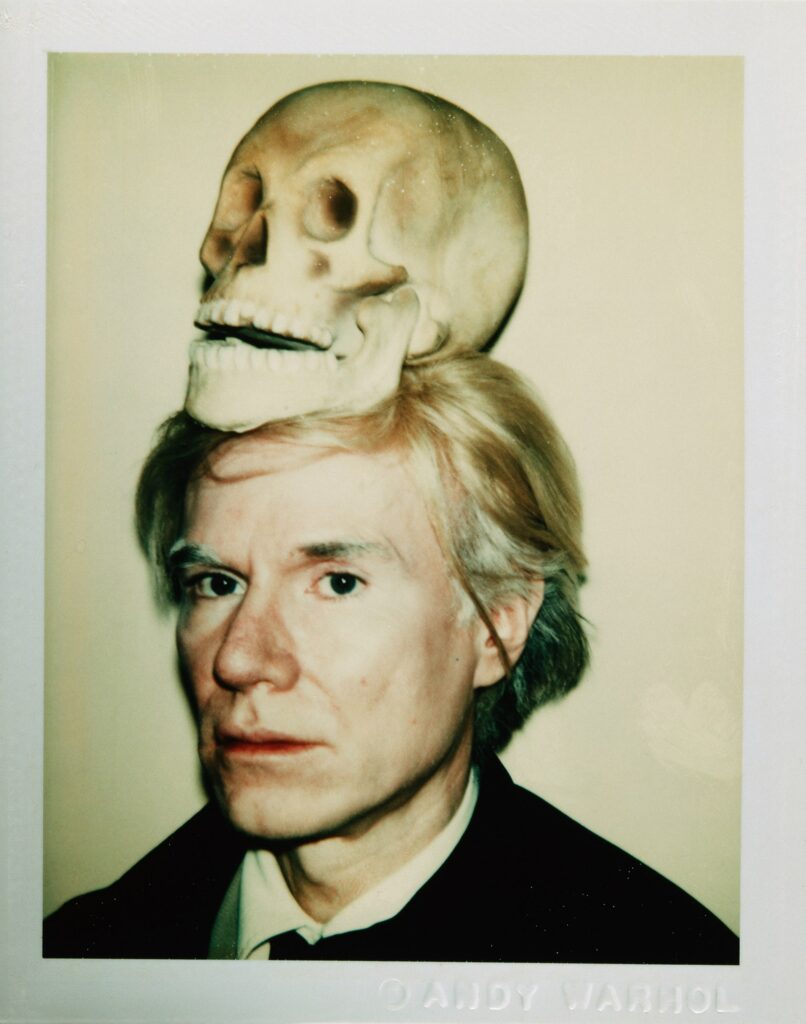

Back in 1982, Andy Warhol was, somewhat infamously, turned into a robot. The machine was made by a Disney Imagineering veteran for a project that never really took off, but Warhol liked his animatronic self. “Machines have less problems,” he once said. “I’d like to be a machine, wouldn’t you?” The artist, who died in 1987, was a master of his own cult of personality, and the robot was practically a manifestation of how the world perceived him: meticulously crafted, if a bit rigid and monotone in his conversational style.

Andrew Rossi knows this. It’s part of the reason the filmmaker felt OK letting an artificially intelligent machine speak for Warhol in his new documentary series for Netflix. Based on a book of the same name, the six-part documentary The Andy Warhol Diaries is partially narrated by an AI reading the stories that the artist told diarist Pat Hackett. The voice sounds just like Warhol—and then you remember the voice the world knew was always a flat and robotic one. Warhol’s work is about questioning iconography and surface-level appeal. He kept his voice flat to maintain that image, to belie how much heart he actually put into it, Rossi says, adding “when he spoke, he continued this superficial performance that was also part of the way he dressed and the way he made art.”

Even still, using an AI voice to speak for a beloved cultural figure—or anyone, really—isn’t without ethical quandaries. Rossi was already editing The Andy Warhol Diaries last summer when controversy erupted around director Morgan Neville using AI to recreate the voice of Anthony Bourdain for his doc Roadrunner. Rossi had been in consultation with the Andy Warhol Foundation about the AI recreation, and the Bourdain doc inspired a disclaimer that now appears a few minutes into Diaries stating that the voice was created with the Foundation’s permission. “When Andrew shared the idea of using an AI voice, I thought, ‘Wow, this is as bold as it is smart,’” says Michael Dayton Hermann, the foundation’s head of licensing.

The Andy Warhol Diaries debuts Wednesday on Netflix.

Courtesy of NetflixBy being upfront, Rossi’s documentary avoids one of the big issues Roadrunner faced. Viewers know from the start that what they’re hearing is computer-generated; whereas a lot of the backlash Neville faced came because his deepfake wasn’t initially disclosed. But that doesn’t mean there aren’t still many unanswered questions about when it is and isn’t acceptable to recreate someone’s voice with a machine. In the Bourdain documentary, the words the AI speaks were actually written by the late chef, but there aren’t real recordings of him saying them. For Diaries, Warhol did once speak all the things the AI Andy says—he told them to Hackett—but they weren’t recorded at the time. Do these caveats make a difference? Both of those documentaries used AI because their subjects were deceased. Presumably, there would be a different set of ethical concerns if they were living. What if it wasn’t just the voices that were recreated? What if their likenesses were, too? AI and other technologies are improving to a point where digital effects can practically create whole performances. The question soon will be whether they should.

Zohaib Ahmed thinks about these things a lot. The CEO of Resemble AI, he’s the one Rossi turned to in order to create Warhol’s voice. But before Ahmed even signed on to the project, he made sure the Warhol Foundation had given consent. Generally, Resemble AI works with the voices of people who are still alive—largely making automated voice responses for call centers and the like—but the company says it remains strict about guidelines. “[Warhol’s] diaries are written in a really interesting way, almost like they’re meant to be read aloud. They’re in his voice,” Ahmed says. “It’s almost like this was an extension of Andy’s work, so we weren’t creating something that was an ethical dilemma for us.”

So the project for the pair felt ethical, but not easy. For one, there was that voice Warhol crafted for himself—a monotone built from his Pittsburgh upbringing and years in the New York City art scene. For another, Ahmed and his team didn’t have a lot of that voice to work with. When the company started, it only had about 3 minutes and 12 seconds of audio data—and needed to create a voice that could read about 30 pages of text. To do that, Resemble’s AI engine used the characteristics—or phonemes—of Warhol’s voice that were in that dataset to predict the phonemes that weren’t in order to create a fairly full voice. That voice was then loaded into the company’s web platform, where users—in this case, Rossi—could type in what they want the voice to say and then ask the AI to make adjustments until it sounds the way they want it to. Being able to have that human involvement, Ahmed says, is “really powerful.” It even allowed Rossi to shift the emotion or have Warhol say words that required an accent—like, for example, the name of his friend and collaborator Jean-Michel Basquiat.

Content

This content can also be viewed on the site it originates from.

Ultimately, the AI didn’t do quite everything based on just those few minutes. Along the way, Rossi brought in actor Bill Irwin to record some lines in a Warhol voice to help the machine learn the proper delivery. “We tried models combining 80 to 75 percent of the AI voices and 20 to 15 percent of Bill’s performance,” Rossi says. “In the end, Andy’s voice throughout the series presents a variation of ranges on this interpolated model.” Some words—“quaalude,” for example, or “Rorschach test” needed more pitch modulation, and sometimes Rossi inserted sounds into the algorithm phonetically, forcing the AI to say things a certain way through creative spelling. “Bear in mind,” the director says, “this is for Andy, who has a Pittsburgh accent but is delivering names and locations over the phone as a veteran New Yorker.”

The Andy Warhol Diaries, then, serves as a reminder of what could be possible. It doesn’t fully answer all the questions currently swirling around the ethics of using AI to bring back long-lost luminaries—but it does demonstrate how close the technology can get to recreating the past while also being transparent about what exactly it is. “When I first heard the AI-created voice,” Hermann says, “I felt confident it was going to be an incredibly effective way to bring Warhol’s diaries to life and humanize the enigmatic artist.” Maybe, in other words, a robot can help us understand him better than anything.

More Great WIRED Stories

Images and Article from www.wired.com