Editors note: Filmmaker and producer Davis Guggenheim directed 2006’s An Inconvenient Truth featuring Al Gore. The film won the Oscar and helped put Jeff Skoll‘s social-impact-driven production company then known as Participant Media on the map, and also sounded an alarm about climate change that has become more pronounced since the film was released. In addition to documentaries, Participant was also responsible for Oscar Best Picture winners Spotlight and Green Book, and Steven Soderbergh’s Contagion, another timely topic. Guggenheim is a co-founder of Concordia Studio and most recently directed and produced Still: A Michael J. Fox Movie, which won four Emmys including for Outstanding Documentary or Nonfiction Special. He is the only person to direct and produce three distinct films ranking in the top 100 highest-grossing documentaries of all time (An Inconvenient Truth, It Might Get Loud, and Waiting for Superman). Here he penned a guest column for Deadline after learning Participant was shuttering.

***

Twenty years ago I sat with a hundred or so others in the auditorium at CAA. Next to me was Jeff Skoll, who had recently founded Participant Media, and together we watched Al Gore give a slideshow lecture about climate change.

Gore had his charts and graphs and methodically he made his case. I had first seen the presentation a few weeks earlier and I was shocked by it. I felt the weight of his message and the urgency behind it. I wanted to help share it with the world but I was dubious about how. I think we all were. How the hell could you turn a slideshow into a documentary — let alone a piece of entertainment?

After the lecture a group of us went upstairs to a small conference room and we all turned to Jeff.

He didn’t blink. “We can’t waste any more time. Don’t wait for lawyers or contracts. Start tomorrow.”

The five of us — Laurie David and Lawrence Bender who both brought us the project, and Leslie Chilcott, Scott Burns and I — jumped into action. Six months later the film, An Inconvenient Truth, was at Sundance. The doubts persisted. After seeing the the movie, the head of a major studio said, “Don’t fool yourselves. No one’s gonna pay for a babysitter to go watch this in a movie theater.”

He expressed a common wisdom. But he was wrong.

Jeff saw something that even those of us who made An Inconvenient Truth couldn’t — that the dollars-and-cents of investing in a film was only part of the calculus. That a film could land. That the right film at the right moment could make an impact.

(L-R) Jeff Skoll and Al Gore at the ‘An Inconvenient Sequel: Truth to Power’ premiere at Sundance in 2017

Gustavo Caballero/Getty Images for Participant Media and Paramount Pictures

So Jeff, like so many of the characters in the films he loved, made a bold choice. With that choice he helped bring Al Gore’s urgent message to millions all over the world and it moved the needle not just with awareness but policy. He changed the conversation around climate change. He changed the field of documentary. And he changed the movie business.

This week, since Participant announced that it’s closing its doors, I’ve received a hundred texts from friends and colleagues mourning the end of the company’s run. There’s also been the inevitable postmortem commentary about whether Jeff Skoll’s 20-year venture was worth it. Look at the ledger, the critics say. Participant never made a dime.

The implication is that Jeff was just another sucker, swindled by Hollywood charlatans. But anyone who worked with Jeff will tell you that he knew exactly what he was doing. Would the cynics have been happier if Jeff had parked his money somewhere to silently accumulate?

Those who look only at Participant’s bottom line miss the bigger picture. Sometimes when you consider only what you can measure, you miss what actually matters.

Jeff made this investment with his eyes wide open. And those who look only at Participant’s bottom line miss the bigger picture. Sometimes when you consider only what you can measure, you miss what actually matters.

To fairly assess the company’s legacy you have to remember the market for documentaries back in the days before An Inconvenient Truth. At the time, I was an aspiring director and I was floundering. I’d pitched PBS only months before on another project and never even received a reply. It was the kiss of death. There was PBS and there was HBO and that was about it for documentary work.

Look at documentaries now.

Look at all the films premiering every year at Sundance, Telluride and Toronto. Look at the range of documentaries available on all the streaming platforms. Even with the current constriction in the market, it’s hard to overstate the expansion of nonfiction storytelling — not only in the growing network of filmmakers making the work but also in an audience that is hungry for more.

This is the industry that Participant cultivated. This is the world Jeff helped create.

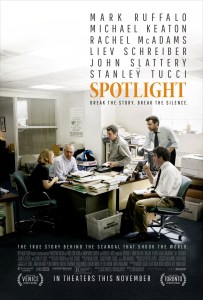

He didn’t do it alone, of course. He had the good sense to hire and empower the best creative executives, including Diane Weyermann, who championed documentaries like Citizenfour and American Factory, and Jonathan King on the fiction side, who commissioned Spotlight and Roma.

Participant also became a beacon for scores of filmmakers out there who, like me, were guided by Jeff’s simple idea — that storytelling can shape how we see the world.

Participant made films about women’s rights, workers’ rights, public education, journalism and racial injustice. They won every award you can name, not just in docs but on the fiction side, too. Some of the movies didn’t work. Some were great but never found a home in the marketplace. Jeff was okay with that. He accepted financial loss in pursuit of something more elusive but in my mind more important.

Hollywood’s in a funk at the moment, with the hangover from the pandemic and the shadow of the strike. But I look past that and I see the returns on Jeff’s 20-year investment in Participant paying off in beautiful, immeasurable ways.

Still, Participant’s absence raises questions for all of us going forward — who will step up as the next champion for the stories that don’t fit in the current business model or the accepted common wisdom? Who will make the next Good Night, and Good Luck, the next RGB, the next Citizenfour or Roma? And what will Hollywood look like if no one does?