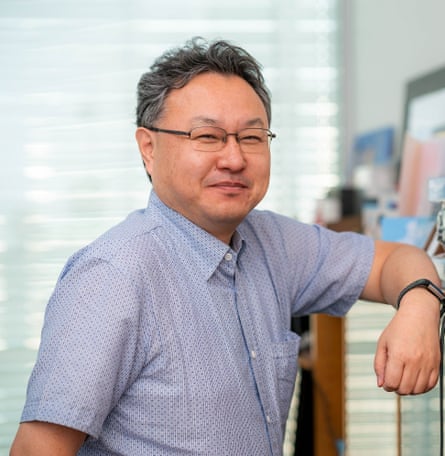

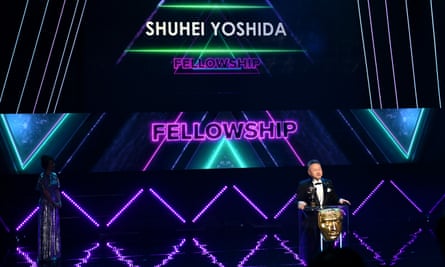

In early 1993, Shuhei Yoshida joined Sony’s nascent PlayStation division as a business development guy – the first member of the team who didn’t have an engineering background. When he was working with Ken Kutaragi and the other architects of the original PlayStation, and later producing games from Crash Bandicoot and Gran Turismo alongside game development legends Mark Cerny and Kazunori Yamauchi, he freely admits that he could scarcely believe his luck. When I speak to him, on the eve of receiving Bafta’s prestigious fellowship award for his contribution to video games, he still seems endearingly surprised by his own success.

“The people who have received [this award] before are all creators! Amazing, talented, genius people! I don’t know how I fit in,” he says. (Previous recipients of the award include Shigeru Miyamoto and Hideo Kojima.) “But everybody says I deserve it, so I guess I deserve it.”

Yoshida is a recognisable face not just for people working in games – he has been a champion of game development for decades, as president of Sony’s game studios from 2008-2019, and has helped hundreds of developers get their games on to PlayStation – but to fans, as well. When the PlayStation 4 was the world’s most popular console, he was a regular face in Sony’s marketing and communications, gently poking fun at the rival Xbox One console or appearing on video game podcasts to discuss games he’d been enjoying.

At 59, he still plays everything, from Sony’s own blockbusters such as God of War and Horizon to independent games from little-known developers; currently he’s got a big Marvel Snap habit going, he tells me, but he’s also been playing the Bafta-winning Before Your Eyes on the recently released PlayStation VR2 headset (it made him cry), and he expresses an enduring admiration for Nintendo’s polish, creativity and tactility. He knows who video game journalists, streamers and influencers are, and posts unselfconscious selfies with them on Twitter. He is, like Nintendo’s fondly remembered late president Satoru Iwata, a gamer first and an executive second.

In 2000, Yoshida was sent to the US to help run PlayStation’s American studios – Naughty Dog (which would go on to make The Last of Us), Sucker Punch and Insomniac. It was here, with Santa Monica Studio, that he worked on his first game-of-the-year winner, the original God of War (2005). It was the first of many. “After that there have been so many game of the year awards, I cannot believe it,” he says. “If you are involved in one GOTY game, that’s a good career I think, but for me it’s been six or seven.”

Behind those successes, though, have been plenty of failures – cancelled projects, developer partnerships that didn’t work out, a lot of work that was never seen by the public. When you work in game development, you get used to that, Yoshida says. “PlayStation embraces new ideas, and many of them fail. We do a prototype, we evaluate, we decide whether to spend more time and resources, or we just stop. We cancel so many games. I usually try to convince the developer that I’m trying to save them from getting stuck with this project … We tend to work with people who have very strong ideas, we love these people, so trying to change or stop their project is so hard. It’s all about talent in this industry. I have tried to help them as much as I could.”

In doing so, Yoshida is often present for the entire lifecycle of a game, from idea to prototype to release, and he sees how hard developers work to realise them. He still counts 2012’s Journey – which he says was an incredibly hard project for its makers at Thatgamecompany – among his career highlights, because it overcame impossible odds. “When that game received all its game-of-the-year awards – not just the best indie game, but the best game, against all these AAA titles, it started something,” he says. “It had such impact on the people who played. You could finish it in four hours but it’s about life and death, and people who have gone through family or close friends passing away could reflect on things they experienced as they played. I am so fortunate to have been involved with it.”

Things have become more difficult for game developers in the 25+ years that Yoshida has been working in the industry. Development costs have skyrocketed: 2010’s God of War III, an extremely expensive game for its time, cost $44m to make. Modern PlayStation 5 games, such as God of War: Ragnarok can cost around $200m. At the other end of the scale, independent developers are coming out with better games on smaller budgets, meaning getting noticed is harder.

“Getting games funded is tough, but even when you make an amazing game, there are so many out there in the market, great games that nobody knows,” he muses. “The good thing is, these days, there are really good high-quality indie publishers out there. When I was in São Paolo last year, there were scouts from Devolver, Curve Digital, Team17, all trying to find the talent from these places, the games that only they can make – [a game’s] cultural background, mythology, artwork, music, can all be something special to stand out in the market… It’s all about economy. Some big games sell tens of millions of units and justify putting all these resources into expensive regions, but I think the industry has to diversify, and I think that will happen naturally and organically.”

after newsletter promotion

Yoshida’s job these days involves reaching out to and developing talent from outside the established game-making regions of Europe, Japan and North America – something that Xbox, PlayStation’s big rival, has also been investing in. And he sees AI tools – which are currently causing a lot of consternation in the creative industries, including games, because of their potential to devalue human work – as something that will open up game development to many more people, and dramatically reduce its cost.

“I was going through 15 pitches in a competition for indies in Japan just this morning, and one of them had amazing beautiful graphics made by a small team of students,” he explains. “They said that they used Midjourney, the AI art generator, to create the art. That is powerful, that a small number of young people can create an amazing looking game. In the future, AI could develop interesting animations, behaviours, even do debug for your program.”

I ask him what he thinks about developers’ expressed fears that AI could replace human effort in these areas – art, music and code. “It is a tool. Someone has to use the tool,” he says. “AI can produce very strange things, as you must have seen. You really have to be able to use the tool well. AI will change the nature of learning for game developers, but in the end development will be more efficient, and more beautiful things will be made by people. People might not even need to learn programming any more, if they have learned how to use these tools of the future. The creativity is more important, the direction, how you envision what you want.”

Yoshida describes video games as a medium that takes every technological advancement and turns it into fun. “The games industry will never cease to be a fun place,” he says. But he is adamant that just like in the 1990s, it’s the talent, not the technology or the business model, that defines its future. “The industry keeps growing and growing, and I hope it keeps supporting and chasing creative ideas and people who try to work on new things. You don’t want to see the Top 10 games every year being almost the same, all games becoming service games … That would be a bit boring, for me.”