If your bag is packed for your summer holiday, does it contain books that you’ve been meaning to read for ages, or titles that you very recently bought or borrowed?

Perhaps you grabbed a bestselling mystery or romance in an airport bookstore, or chose an intriguing-looking celebrity memoir from a little free library in your neighbourhood.

Maybe you loaded up your e-reader a few weeks ago with titles that were recommended to you on the basis of your most frequently read genres, or that you saw featured in a “summer reads” list in a newspaper, website or book blog.

If you’re a reader, at least one of these scenarios will be familiar to you. But the chances are that your summer reading choices have been influenced by someone you know and trust, whether that person is an influencer on Bookstagram, a colleague or your best friend.

We may have online access to a recommendation culture that supplies us with reviews, star ratings and book promotion buzz, but how we choose books is significantly influenced by our offline relationships and book-browsing habits.

Even for those of us who regularly use social media platforms like YouTube, Instagram, Goodreads or TikTok to find out what other readers recommend, suggestions offered by friends, family members or colleagues remain the main way of picking our next book to read, according to our recent research.

Longer hours of daylight … to read

For many Canadians who enjoy reading books for pleasure, the summer season brings with it some extra reading time. Longer hours of daylight and, if we are lucky, a summer vacation allows us to tackle the TBR (to be read) pile, or to reach for a lighter “beach read.”

As a practice, summer reading in North America has a history stretching back into the 19th century, when an increase in literacy, the mass production of more affordable books, the provision of electricity to many towns and the proliferation of public libraries all combined to create the conditions for leisure reading for those with access to these resources.

Fast forward about 150 years and we find ourselves in a post-digital age: as noted by scholars like Alexandra Dane and Millicent Weber, digital technologies and platforms have changed and complicated how books are produced, and how they circulate and are consumed.

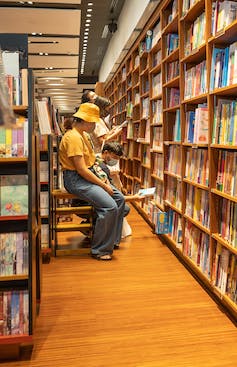

A trip to the library now consists of a few mouse clicks to borrow an audiobook or comic, while a browse through a bricks-and-mortar bookstore may include skimming through paperbacks on the “BookTok Books” display table that curates notable books promoted by TikTok influencers.

Opinions on ‘bestsellers’

Our research involved an online questionnaire with more than 3,000 readers, interviews with social media influencers and a two-month asynchronous conversation with international Gen Z readers in a private Instagram chat space.

The readers we surveyed frequently combine traditional methods of book selection such as consulting reviews in newspapers, and browsing in libraries and bookstores, with the use of online recommendation sources.

We learned the label of “bestseller” is a further resource for choosing books.

This is the case regardless of whether “bestseller” is signalled by a sticker on a book’s cover, by a publisher’s advertisement or by a BookTuber’s roundup of #summerreading. And, it’s true even when readers view “bestseller” as a term that screams “not for me,” “trashy” or “poor-quality writing” — as many of our surveyed readers did.

(AP Photo/Paul White)

Trusted influencers

But for every reader who dismissed bestsellers, there was a reader for whom the word bestseller was an invitation to research that title further. Add in a recommendation from a friend or a trusted online influencer like Canadian Ariel Bissett, and a reader is highly likely to at least try out the book.

Gen Z readers are especially likely to use a range of sources and media when choosing a book, including finding their way to the next read via a film adaptation, TV show or videogame tie-in.

Among the people we surveyed who responded to our survey question about the various — and combined — ways that they choose books, “favourite author” (73 per cent) and “friend’s recommendations” (72 per cent) were the top two means of selecting a book.

“Prize winners” and “family member’s recommendations” were also significant, with 40 per cent of respondents indicating both of these as their go-to methods. Thirty-five per cent of readers identified “work colleague’s recommendations” as trustworthy.

Young adult readers

(Shutterstock)

Another aspect of our research highlighted how readers engage with reading recommendation cultures online and offline. This research involved a two-month conversation with an international group of young adults from 13 countries living on five continents.

These readers look for books that reflect their concerns about climate change, mental health issues and the experiences of their own communities, especially if their communities are racialized and/or discriminated against in terms of gender, language and abilities.

For this generation of readers, making ethical choices not only based on who or what is represented within the pages of books, but also about where and how to buy or borrow books, are important.

A book to engage us

Summer in Canada affords readers the opportunity to pick a new book to read. Some will be guided by their favourite authors or genres. Others will make choices inspired by their ethics or political commitments. As readers, we all want to invest our time in a book that will engage us, whether for entertainment or education.

If we’ve made a successful selection, we are very likely to tell friends about it, or to go online and share our reading experience with other readers through social media posts or Reddit reviews.

In these post-digital times, we are perhaps more likely to judge a book by its readers than by its cover.