By any indicator, filmmaker Sean Wang has had a career year–and we’re only in Month Two. His narrative feature debut, Dìdi, captured the Audience Award and a Special Jury Award for Best Ensemble in the US Dramatic Competition at the recently concluded Sundance Film Festival, and that same week, he earned an Academy Award nomination for Best Documentary Short Subject for Nǎi Nai & Wài Pó (Grandma & Grandma). What’s more, Focus Features acquired Dìdi for a mid-summer release, and Nǎi Nai & Wài Pó just premiered on Disney+ as part of the streamer’s “People & Places” series.

(From L) Director Sean Wang, Chang Li Hua, Yi Yan Fuei, and producer-cinematographer Sam Davis attend the Oscar Nominees Luncheon.

Valerie Macon/AFP via Getty Images

This is not to dub Wang, 29, an overnight sensation, mind you. Dìdi was six years in the making, earning support from various Sundance Institute labs and Google Creative Labs. And during that gestation period, he made a number of shorts, including Nǎi Nai & Wài Pó, a charming slice-of-life capture of his two grandmothers as they exude the day-to-day joys of living–dancing, singing, cosplaying action heroes, cooking–while ruminating on the pains of aging and loss. Both widows, Nǎi Nai (Wang’s paternal grandmother, Yi Yan Fuei) and Wài Pó (his maternal grandmother, Chang Li Hua), live together in a house in Fremont, Calif., where the filmmaker grew up.

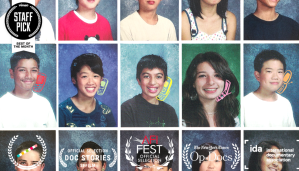

‘Have a Good Summer’

SeanWangFilm.com

Wang’s nonfiction canon, mostly accessible on his website, explores a litany of interrelated themes: intergenerational bonding; the challenges of being an immigrant and the sacrifices they make for their children (Wang’s parents immigrated from Taiwan); expectations of first-generation children of immigrants; and the idea of home, assimilation, and what one leaves behind. There’s Wang’s 2016 work 3,000 Miles, a contemplation of a year in New York City, underscored by a series of voice-mail messages from his mother calling from across the country; his 2021 NYTimes Op-Docs piece Have a Good Summer, in which his middle-school yearbook serves as a cinematic foundation for reuniting with his classmates via recorded phone conversations about specific memories and deeper ruminations about the sacrifices their parents had made for them; 1990 (2021), a two-minute reel of home videos of his sister and him, from their respective births to present; and Still Here (2020), in which Wang travels to his grandmother’s old village in Taiwan–now suffering from both neglect and gentrification–to interview her former neighbors who have elected to stay.

“They all come from a very personal place,” says Wang. “They start from a question to a feeling that I have of exploring what it feels like to come of age, and what it feels like to be a first-generation immigrant kid and figuring out this worldview that is specific to me, but also specific to everybody who shares that intersectional identity.”

‘Dìdi’

Focus Features

“When you dive into this very personal lens, you actually access a very universal audience and a very universal emotional bracket,” Wang continues. “A lot of those films were made in the last six or seven years. And I started writing the feature film [Dìdi] about seven years ago, so many of the things I was thinking about, I was putting into the feature. [With the shorts], I was finding other containers to explore those feelings and emotions.”

Given that these works all draw from Wang’s personal narrative, he manages to transform what are, on the surface, home videos, into indelible works that resonate with a bigger audience. “I think it goes back to this idea of, Who is your audience?” he explains. “People always talk about this idea of an audience as this ambiguous sea of people. But at the end of the day, you’re an audience member, I’m an audience member, my friends are audience members, and we all watch movies, we all look to a screen as entertainment….In the last few years, the common thread about all these films is, the audience in my head is much, much, much smaller. With Have a Good Summer, for example, as I was working on it, I thought to myself, If this still doesn’t feel honest, if it doesn’t work for me and my friends, it’s not going to work for anybody. But I think it really nails the hyper-specific experience. If my friends are able to see the honest version of themselves in this film, a much bigger group of people are able to see a version of themselves in this experience.

‘Nǎi Nai & Wài Pó’

Disney+

“The fact that other people can see a version of their grandmothers and their relationship with their grandmothers [in Nǎi Nai & Wài Pó], that says a lot about the empathy and the experiences that can translate across cultures, across different backgrounds.”

Wang and his DP/producer, Sam Davis, had no trouble convincing Nǎi Nai & Wài Pó to participate in the short. Indeed, the grandmothers share in the film how much younger they feel when the filmmakers are around, and how much quieter their house is when they’re away. “It was so organic and small and intimate,” Wang recalls. “We would shoot for a little bit and then they would go take a nap and then we would shoot. It was eight days of just following what feels good, what feels right, and what feels honest.”

‘Nǎi Nai & Wài Pó’

Disney+

“I had made things with both of them over the course of the last decade, whether I shot on my phone or a camcorder.” Wang continues. “We had done little skits together; they’re used to this idea of me filming them and showing them something. So Nǎi Nai & Wài Pó was an extension of that. It was really trying to make something that was worthy of the big-screen experience, because they are worthy of the big-screen experience. Their stories are so deep and complex and layered. We wanted to make a movie that was about the silliness, about that childlike youthfulness, that joy, without ignoring the pain of their lives–what it feels like to grow old, what it feels like to feel your body get weak, what it feels like to see your friends pass away and think you might be next.”

Wang had lived with his grandmothers for a time, prior to making his short, which afforded him the opportunity to observe them carrying out the mundanities of their daily lives–-cooking, washing dishes, reading the newspaper, doing laundry. But in making this film, was there something that he discovered about them that he hadn’t known before?

“I knew so much of the broad strokes of their lives, their lives before they were my grandmothers,” Wang explains. ”But I think through this experience, I got to really understand and see the emotion and know the stories behind those broad strokes: what it felt like to go through those things, and who they were as people before I knew them, before their identity became my grandmothers. It was just getting to know a version of my grandmothers on such a deeper level. And knowing that they always had this creative, playful, silly side, this film really gave them an opportunity and a platform to bring that to life in a way that no one has ever really given them the opportunity to do. That, to me, is the greatest joy: They get to, at ages 86 and 96, discover something new about life and this opportunity to play.” (Chang Li Hua, Wang’s maternal grandmother, plays a substantial supporting role in Dìdi).

Sean Wang at the Deadline Portrait Studio during the 2024 Sundance Film Festival.

Michael Buckner for Deadline

With each film Wang has made in his brief career, he has learned something about himself and his place in the world. With Nǎi Nai & Wài Pó, “This film was a really good reminder of two things: One, sharing space doesn’t just mean spending time with somebody. In our day-to-day lives, we can often fall into these traps of being around the people you love, but you’re on your phones, you’re on the internet, you’re working. Just because you’re in the same space as somebody doesn’t necessarily mean you’re being present with them. And hopefully, this is a takeaway that audiences have too. But I think what this film allowed me to do was really be present with my grandmothers in a way that it was a collaboration, in a very intimate sense. Getting to spend 17 minutes with them [as an audience member], you learn so much about the world. You learn so much about your outlook on life.

“One thing that Sam and I talked about a lot was, Hearts don’t cost anything. This project was so intimate. It was so small in scale. But it was made with a lot of heart; with the most special projects, the most meaningful projects, that’s where they come from. They don’t always need to have A-list talent attached; they don’t need to be the high-profile projects. The ones that end up becoming the most special, that resonate with the most people, are the ones that come from inside you.”