“For me the work is about asking questions about the complexity of the world that we all share,” the Canadian artist David Hartt told me, while discussing work that he is showing at this year’s Art Basel Miami Beach. “The way that I inhabit a political position is through an oblique set of questions that I attempt to open up in the same ways a prism does, to break a really complex situation into its component parts so that we can better understand how it’s operating.”

Hartt was sharing his perspective on the notion of “protest art”, which is a theme of sorts at Art Basel this year. Perhaps more than in other years, artists are showing works that speak to politics, causes and longstanding issues around human rights. While much of the art this year is informed by such notions, artists had varying reactions to construing their work as an act of protest, often voicing unease with seeing their art as a political gesture.

The work that Hartt was showing, an elaborate, intriguing tapestry titled The Histories (after Church), version with xenoformed atmosphere / Rayleigh scattering spectrum shift, is an apt example of how politics and history can be layered into a piece that is ultimately sophisticated and open to interpretation. Examining ideas around slavery, colonialism, terraforming, alien species and the biosphere, The Histories is a work that wears its heady intellectual pedigree quite lightly.

The Histories is partly inspired by the work of Frederic Edwin Church, a major voice in the Hudson River School of landscape painting and also an abolitionist. For Hartt, Church was a way into the complicated discourses around history, politics and economy that he seeks to implicate in his art. “Church, for me, is a synthetic figure, somebody who is in the process of trying to work within and expand the boundaries of historical narrative and social categories operational within the 19th century. I see him as being a really beautiful cypher.” Hartt aspires to make The Histories a seductive and sensual work that draws a viewer in, ultimately catalyzing conversations around a set of very important ideas.

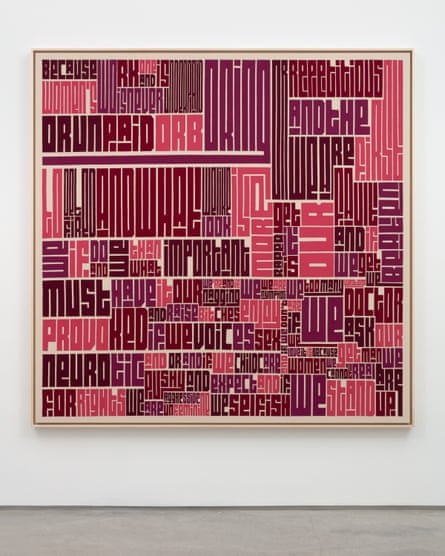

Another tapestry striking a quite different note is Egyptian artist Ghada Amer’s Because, a beautiful piece done in a palette of maroons. The work uses a textile process that, according to Amer, has ancient roots and dates back to the time of the pharaohs, and which nowadays is associated with producing tents for special events like funerals, weddings and political rallies. Creation of these textiles is in decline because of cheaper modern alternatives, and Amer was asked to work with them in her art as a way of reinvigorating the dying industry. “In the beginning I wasn’t interested at all,” she said. “But then I said, ‘OK, I’ll try it,’ and once I did it was like, ‘oh wow,’ I was really inspired. I was surprised by what I could do with it.”

Amer’s square tapestry is filled with English-language words of varying shapes and sizes drawn from a 1975 Australian feminist declaration that Amer happened to come across. Although written decades ago, the critique in Amer’s text still feels contemporary. “Everything has been said and very little has been done,” Amer said. “Sometimes very ancient quotations look very modern.”

Part of what makes the work feel so compelling and original is how Amer draws on calligraphy traditions to create a form of written English that is at once beautiful, mysterious and somewhat undecipherable. “We designed something on the same principle as Arabic calligraphy – you can stretch out words, you can put them wherever. In that way, the words become the form itself, it becomes like a figure.” This highly stylized English challenges a viewer’s attempt to read it, forcing audiences to engage with the text of Because less as a political message and more like a piece of art that each will interpret in their own way. “It was a bit of a risk for me,” said Amer. “I wanted to do something new, and I worked for three years on this series.”

Donald Moffett offers a much more abstract work – a longtime crusader for LGBTQ+ rights with Act Up, his most recent art is not about civil rights but rather the degradation of the Earth’s biosphere. He is showing Lot110123 at the fair, a striking addition to his ongoing Nature Cult series, through which the artist has engaged the climate crisis via a diverse array of striking and mysterious works. “Nature Cult is an ongoing umbrella category of work. The whole use of the word “cult” tends to stand the hair up on people’s necks. But the way I talk about it is, let’s all join the cult, all seven billion of us.”

Moffett created Lot110123 from several pieces of the plentiful driftwood that washes up regularly on the beaches of Staten Island, where he lives. “I love it in Staten Island,” he told me, “it’s the ugly stepchild of the five boroughs. There’s all this driftwood that comes in like manna.”

In order to build his piece, Moffett used joinery to integrate the driftwood together until it appears as a single, beautifully tangled mass, with birdhouses improbably sprouting up from it. The most striking things about Lot110123 are the intricate textures found in the driftwood that Moffett has selected for this piece and the unmistakable ultramarine color. “It seemed to be the perfect color because this wood is coming out of the sea,” he said. “This ultramarine was just insistent. It expresses so beautifully on this wood with all of its texture.”

Moffett connected his transition away from protest and toward a more abstract body of work with his transition away from political action and toward the privacy of the art studio. “Things were winding down, and it was time to retreat to the studio and be more in the private practice of art. This is what happens in the studio when you’ve lived through all that street work.”

Artist Chakaia Booker’s Flip Technique and Weighted Balances are gloriously tactile works that the artist created out of repurposed rubber. “I see rubber as a raw material like stone, wood, or steel,” she explained. “It can be used in a modular way, creating both intimate and monumental experience for the viewer and myself. I see rubber as capable of opening dialogs about consumerism, mobility, environmentalism, materialism, class, race, culture, and socioeconomic disparities.” Beautiful, intricate and somewhat foreboding, Booker’s rubber works are impressive for their size and for the strange forms that the artist was able to wrest out of her materials. “Making sculpture in this way is a physically and intellectually demanding process. It requires the whole body to work the material, and all my attention to fit the details into the larger whole.”

Ultimately, each of these four artists had different perspectives on the degree to which politics and protest should be a part of their work as artists. For Hartt, “it was a question that every artist should be confronted with,” since he believed that “the act of occupying space is a political act”. Yet Hartt also recognized that art will not be boiled down to a single message or action, seeing art as fundamentally about inquiry and complexity. Booker came down in a similar place, telling me that protest was not a part of her artistic practice. “I don’t see my work as protesting, I see it as promoting or encouraging looking at the world differently. Art at its best should help us see the world as capable of changing, capable of evolving to something better by showing us who we are and who we can be.”

For Amer, art was above all about having an experience that starts out as compelling and over time develops layers and layers of meaning. She saw this as distinctly different from protest, which seeks to communicate a message directly and immediately. “I want to make something that is beautiful, it’s enjoyable, but I’m not here to make a manifestation. To protest is to have something dragged in your face. My art makes a statement, yes, but it’s very abstract, it’s not to teach you something. You have to live with something and slowly come to an understanding of it.”