A powerful new documentary about the life and work of Christopher Reeve has premiered to tears and applause at this year’s Sundance film festival.

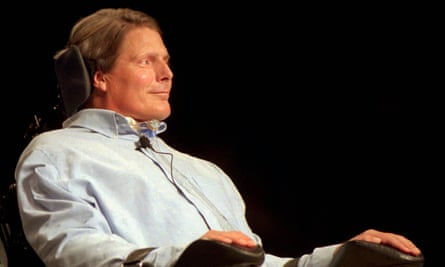

Met with a rousing standing ovation, Super/Man: The Christopher Reeve Story traces the career and activism of the Superman actor before and after the 1995 accident that paralysed him from the neck down.

The film, directed by Ian Bonhôte and Peter Ettedgui, features an intimate collection of home video footage and new interviews with Reeve’s three children and the actors who knew him. Reeve, who died in 2004 at the age of 52, narrates a lot of the film, his words transplanted from the two audiobook versions of his memoirs.

It begins with new year’s eve 1994, a time Reeve looked back on as when both his personal and professional lives were “perfectly balanced” but “in an instant everything changed”.

The actor was so allergic to horses that he had to load up on antihistamines to shoot the riding scenes from 1984’s Anna Karenina, yet riding became an important part of his life. In May 1995, he was thrown from a horse during an equestrian competition and at the age of 42, his life suddenly hung in the balance.

During his time in hospital, Reeve was “unable to avoid thinking the darkest thoughts” with hallucinations clouding his mental state, unable to move beneath his neck. There was fighting within his family as his mother thought he should be taken off life support.

His first lucid words were to his wife Dana: “Maybe we should let me go.” She responded: “You’re still you and I love you.”

The film shifts back and forth from Reeve’s earlier career to the aftermath of his accident, life before and after the unimaginable.

In the early 1970s, he gravitated toward theatre, which felt like home as his childhood had been “so fucked up” with an acrimonious divorce at the age of three. “It felt like he lived on shifting sands,” says his daughter Alexandra.

His old co-star Jeff Daniels recalls working with him on stage in a play also starring William Hurt when the Superman audition came up. “Don’t go, you’re gonna sell out,” Daniels recalls Hurt warning him.

But at the age of 24, the “skinny little kid” with shoe polish in his hair for the screen test, won the role. His children remember an urban myth within the family that apparently his otherwise unimpressed father ordered champagne when he found out, yet only because he was mistaken and thought that his son had secured a role in George Bernard Shaw’s Man and Superman. When he found out, he didn’t approve.

“It was difficult to breathe easy when he was around,” Reeve says of his father.

Reeve remembers being eager to star alongside Gene Hackman and Marlon Brando, but found the latter to be difficult and uninterested. He “took the $2m and ran” while “phoning it in”. It was different for Reeve. “For dad, Superman needed to be art,” his daughter says.

The film was a giant hit, but Reeve’s heart wasn’t in the sequels (he called Superman IV “a catastrophe from start to finish”), retreating to stage and making films that were less commercially minded. The trappings and pressure of playing the character of Superman also affected him. “I am not a hero, never have been, never will be” he said at the time.

His relationship to British modelling agent Gae Exton, which brought him his first two children, was put under strain from being in the public eye, the pair criticised for not getting married and the work taking its toll. Exton was “effectively a single mom”.

Their relationship ended and he soon met Dana Morosino, an actor and singer, and they got married in 1992 and had a son the same year.

The film details just how difficult life was for Reeve after the accident, affecting everything from his bowels to his bladder to his skin to his speech. “He was so terrified that he could die at any moment,” recalls friend Glenn Close.

But rehab became a magic place for him, pushing him out of isolation along with the support from various celebrities including Robert De Niro, Katherine Hepburn and Paul McCartney. Caring for him back at home would end up costing around $400k a year.

Advocacy became vital for him, his new life showing him just how ill-fitted the world was for people with disabilities. “America does not let its needy citizens fend for themselves,” he said in a rousing speech at the Democratic National Convention in 1996.

But the film also details the tensions that came with. While he became the most famous face of the movement, his desire to help further research into a cure was both “galvanising and polarising”, with a controversial commercial using visual effects to show him walk again leading to a backlash.

His three children play a key part in the documentary and detail how his approach to parenting changed after the accident, de-prioritising often overly competitive activities and engaging with them on a more personal level. “I needed to break my neck to learn some of this stuff,” Reeve says.

After developing an infection in 2004, Reeve died soon after, and his wife also died within a year from lung cancer. “That was the moment, I’ve been alone ever since then,” their son Will says.

His friendship with Robin Williams is a key tenet in the film, the pair graduating from roommates as twentysomethings trying to make it in the industry to A-listers in Hollywood. Williams then became one of Reeve’s closest and most loyal friends after the accident, hosting a party every year on the anniversary of his accident. Wrenching footage after Reeve’s death shows a bereft Williams, struggling to gain composure. “I’ve always thought if Chris was still around, then Robin would still be alive,” says Close.

The film ends with hope, celebrating the legacy of the foundation created in Reeve and his wife’s names with the three children carrying on the work. Late in the film, a quote from Reeve recalls what he used to think about when someone would ask him what a hero was, his answer changing from before and after the accident.

“A hero is an ordinary individual who finds the strength to persevere and endure in spite of overwhelming obstacles,” he said.