In Japan, you can set your watch by the arrival of a train. “Delays” (if that’s the word) tend to be calculated in seconds – not minutes or hours.

“This precision results from a combination of advanced technology, meticulous planning, and a deep-rooted cultural emphasis on punctuality and respect for others,” notes the website ScienceABC.

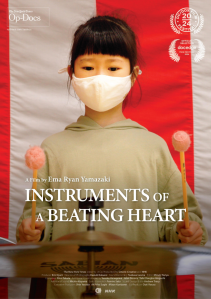

But how do you cultivate a society that values punctuality and respect for others? The key can be found in the country’s primary school system, observes filmmaker Ema Ryan Yamazaki. Her Oscar-contending documentary Instruments of a Beating Heart, a New York Times Op-Doc, goes inside a typical Tokyo school where kids are preparing to complete first grade. Yamazaki herself is a product of that educational environment.

“If you wonder why Japan is the way it is, why our trains run on time, why there’s no trash on the streets — we’re not born that way,” Yamazaki tells Deadline. “I think we’re really taught to be a certain way. And when I look back and think of those six years [of primary school], I learned how to be Japanese.”

The director adds, “I think how kids are being taught, what kids are being taught, especially at a young age, maybe is an indicator of where that society is headed.”

New York Times

Instruments of a Beating Heart follows Ayame, a schoolgirl eager to take part in a group performance of “Ode to Joy” from Beethoven’s 9th Symphony which is being organized to welcome the next crop of first graders. “Discover the joy of being useful for the new first graders,” the music teacher tells kids (the subtle message: don’t think only of yourself).

Ayame wins the audition to crash a cymbal to Beethoven’s beat, but in the ensuing days she arrives late for practice and rehearsals demonstrate she’s been slacking off in preparations meant to be done at home.

“Those of you practicing a lot are getting better. Your hearts are becoming one. I can hear it. But those who are not practicing are ruining that togetherness,” the music teacher reproves. “What a shame.”

Called out at rehearsal, Ayame cries. Teardrops cascade onto her hoodie.

“Some might think it’s a bit too harsh,” Yamazaki acknowledges. But that’s not her personal takeaway. “I really think you see in the film the value of challenging kids to overcome something, and through the experience of that, them really growing. I was little Ayame and I feel like my work ethic and my responsibility, whether it’s to myself or my work or the community I belong to, really was fostered in this system.”

Later, a still weepy Ayame tells classmates, “There’s so much pressure.” A boy runs to her side to share words of encouragement. “I make mistakes too, even though I practice,” he says. “Shall we give it a try?”

“My husband and producer [Eric Nyari] tells me in the U.S. it’s all about being different from the person next to you at a young age. You’re taught to be unique, have your personality. Whereas in Japan, you start by figuring out how you belong within your group, what you are responsible for, what your role is, and you figure out your identity through being part of a community,” Yamazaki comments. “When you start with community, these kids can really feel for one another as though it were themselves because they have such empathy with their classmates. Again, we’re taught to really care about each other. We’re all in it together. Bringing hearts as one in a musical performance cannot be more symbolic of that, I think.”

Does Ayame hunker down and rise to the symphonic occasion? You can watch the film to find out — the link is below. Yamazaki offers a hint: “She really learned what it takes to be responsible for her part,” she says. “And we kind of see that through her journey.”

The film is nominated for Best Documentary Short at the IDA Documentary Awards, which will be presented in Los Angeles on Thursday.

Instruments of a Beating Heart was adapted from a larger film Yamazaki directed called The Making of a Japanese, “where the school itself is the main character, and you meet all sorts of kids and teachers and you kind of go through the school year, again with the idea that this is how maybe a Japanese person is made.”