“Everytime I put on my costume and I jump off the pole I feel a great sense of freedom” says Irene García, a 33 year old voladora – or flying woman – from Cuetzalan del Progreso, a mountain town in the Mexican state of Puebla.

The Danza de los Voladores (Dance of the flying men) is a prehispanic indigenous ceremony that begins with performers dancing around a 30-metre pole before climbing to the top. After securing themselves with a rope around their hips, they launch themselves off headfirst, spinning around the pole towards the ground with their arms open wide.

-

Above: Voladores dance around the pole before climbing up and flying during the celebration of Semana Santa. Right: Irene García climbs up the voladores’ pole. Below right: Voladores atop the pole, seen from the Templo Parroquial de San Francisco de Asís, Cuetzalan del Progreso.

“There are normally five participants. Four represent the natural elements: fire, water, air and wind. The fifth participant is a representation of the sun,” said Irene, who started performing when she was 15. The ceremony is one of the most impressive traditions that have existed in Cuetzalan since Prehispanic times.

But until recently, the ceremony was only ever performed by men. Irene is one of a group of women in Cuetzalan who have challenged that custom, joining in the ritual and opening up new spaces for women to participate.

Cuetzalan del Progreso sits amid mountains, forests and waterfalls. The area has a large indigenous population, of Nahua and Totonac heritage. “It’s difficult to tell where the dance first originated. I personally think the tradition of the flying dance was born in different parts of Mexico at the same time,” Irene told me.

What is sure is that the ritual has changed over the centuries. In prehispanic times it was performed as a way to communicate with the gods and ask for a good harvest. After the arrival of Spanish colonizers, the dance became a tribute to Catholic saints during religious festivities. In Cuetzalan, which has become a popular tourist destination, the ritual is nowadays not only performed during festivities but also on ordinary Sundays. Tourists flock to the main cathedral in the town square to witness the spectacle.

-

Above: Yolanda and Xochitl Morales in their family’s milpa field. Yolanda and Xochitl are the first female practitioners from their family flying group. Atmolon. Right: Julisa Varela and María Azucena Vázquez, two Voladoras from Zoactepan, Xochitlán de Vicente Suárez, Puebla. Far right: María Azucena Vázquez displays her voladora costume in Zoactepan, Xochitlán de Vicente Suárez, Puebla. Below: Yolanda Morales shows her cruzado, the front part of the voladores’ costum.The two warriors embroidered are the symbols of her voladores group that is called Águilas Mensajeras.

The practice is normally passed down, generation to generation among the same family. But there are exceptions.

Irene, for example, had no family members involved in the dance, and her mother was outraged when she first announced that she was going to join the dance. “My family were worried about the risks I would face. But eventually they supported my decision”, Irene explains.

Before Irene, the first generation of flying women had to overcome many prejudices and discrimination in order to be accepted in the dance. Women were often considered too weak to fly, or they were derided for “wanting to act like men”.

-

Jacinta Teresa, a 50 years old voladora, is currently the oldest female performer who is still actively participating in the dance.

“Sometimes I felt that other flying men were jealous of me because I was allowed to perform as a woman” said Jacinta Teresa, 50, a voladora from the first generation of flying women. Jacinta is currently the oldest female performer who still actively participates in the dance.

In a social context which can still be quite conservative – and in which gender roles are starkly defined – it is hard not to see the act of flying as a metaphor for liberation: the flying women represent a rupture with ancient traditions and a step towards a more equal society.

Nowadays, it is increasingly common to see female participants within groups of voladores. “We know that taking part in the dance is a commitment towards our community,” says Yolanda Morales, a 22-year-old voladora from the town of Atmolón. Support for flying women has grown among the local community.

But female flyers still face some more barriers than their male counterparts. Once they get married or have kids it’s almost impossible for women to keep flying, as they are expected to take care of their household, while in many cases working full time jobs.

Because of such challenges, only a few women continue to fly past a certain age. Although some of the flying women are unmarried, others have formed relationships with men in their group. This is, for example, the case of Irene, who met her partner Arturo Díaz on top of the flying pole when she was 18. They share their passion for the dance and have passed it onto their daughters, especially Nikté, who started flying at six.

-

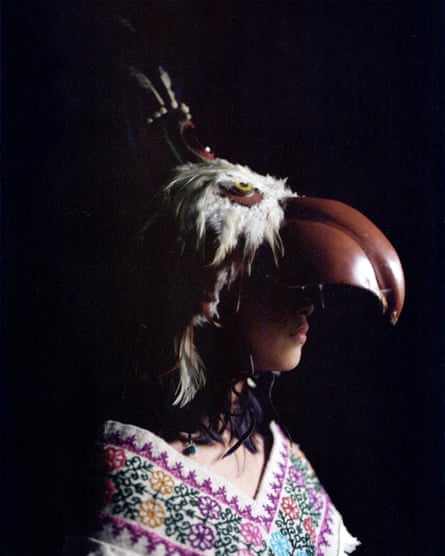

Above: Arturo Díaz helps his daughter Nikté to put on her eagle helmet. Cuetzalan del Progreso. Right: two voladoras’ hats: the white veil and feathers represent purity while the colourful strips stand for the colours of the rainbow. Zoactepan, Xochitlán de Vicente Suárez. Far right: Yohualli Nikté Díaz poses in her house with her eagle costum. Cuetzalan del Progreso, March 2022.

Nikté, who’s now 12, forms part of the newest generation of voladoras. At her very young age she already shows great commitment to the tradition – and to the fight for an equal society. “I don’t understand why women couldn’t take part in the dance. In my opinion the pole symbolizes motherhood. Before the flight, we tie a rope around our belly; it’s almost like we are tied to an umbilical cord”.

Irene takes up the theme, pointing to the dance’s strong connection to fertility, . When a volador flies off the pole to the ground it is like a flower that lets its seeds fall off. “It’s the circle of life: we come to this earth, we grow and we die, returning to the earth”.