Shared from Culture

The Lord Mayor of Liverpool is wearing a nervous smile and a gold ceremonial chain the size of a saucer, the kind worn to greet royalty or a foreign dignitary—which feels appropriate, because it’s not every day you get a visit from the Egyptian king. It’s a cloudless fall day in the city, and star Liverpool forward Mohamed Salah has come to the town hall to film an interview with an Egyptian TV channel. The producers wanted somewhere aspirational, opulent, to film their national icon, and honestly they couldn’t have picked better. The building is ostentatiously beautiful, late Georgian, all Corinthian columns and gold-filigree cornicing and crystal ballroom chandeliers that the Lord Mayor, a tiny woman named Mary, informs me each weighs a ton. The staff buzzes around nervously, chattering in low voices while the cameras roll in the next room. Salah! Even Mary, an Everton fan—and thus a supporter of Liverpool’s most hated rivals—is excited. “I’m not a bitter Blue,” she whispers, because all rivalries aside, who doesn’t love Mohamed Salah?

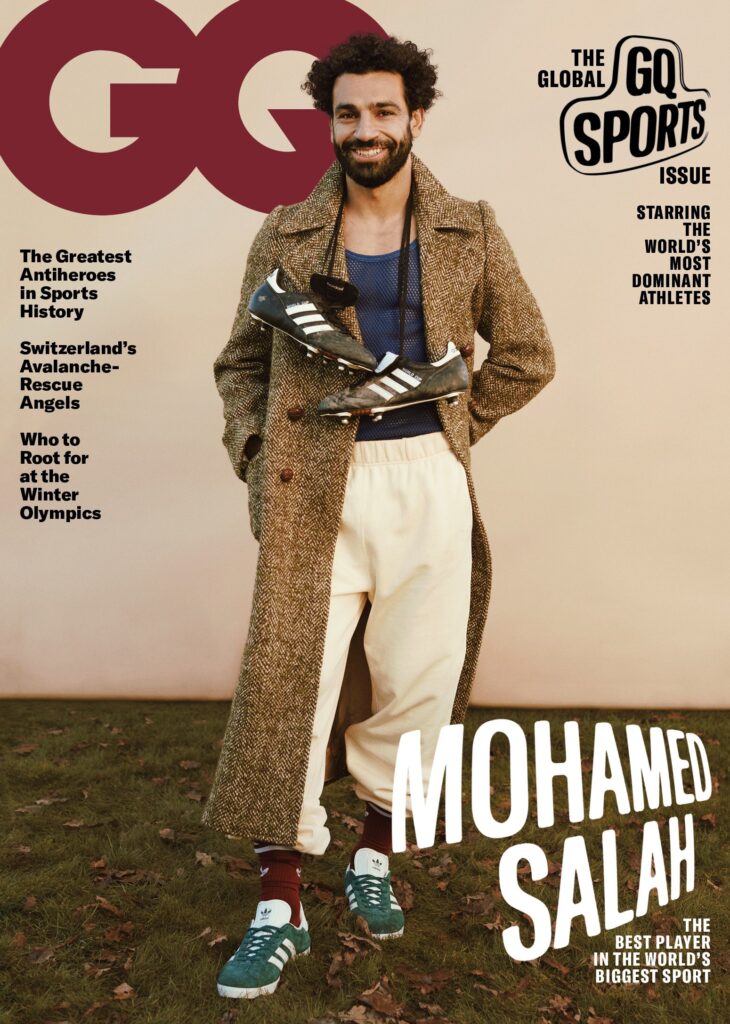

Mohamed Salah covers the February 2022 issue of GQ. To get a copy, subscribe to GQ.

Coat, $5,300, by Gucci. Vintage tank top from Melet Mercantile. Pants, $495, by Winnie New York. Sneakers, $80, and cleats (worn around neck), $160, by Adidas. Socks, $18 for pack of three, by Adidas Originals.In Egypt, where his life story is taught in schools, his nickname is the Happiness Maker. This is as much for his feats on the field—where he has in five seasons led a resurgent Liverpool to Premier League and Champions League titles, breaking umpteen records on the way—as his feats off it. He’s got that million-lumen smile; the Afro-beard combo; the whole wholesome, hardworking, family-man image. In Nagrig, the village in the Nile Delta north of Cairo where Salah grew up, his generosity is legendary: He has paid to build a school, a water-treatment plant, and an ambulance station there, and every month his foundation provides food and money to the destitute.

Tales of Salah’s beneficence occur so regularly that stories about it occasionally now crop up that aren’t even true, but because Salah almost never gives interviews, nobody is around to dispel them. Others are true but would seem fantastical if there wasn’t video and/or photographic evidence to confirm them, such as the time a bunch of assholes were picking on a homeless man at a Liverpool gas station, only for Salah to show up in his Bentley and defuse the situation, before giving the homeless guy money for somewhere to stay. (True.) Or the time that a thief stole 30,000 Egyptian pounds—about $1,900—from Salah’s father’s car, and the police caught the culprit, only for Salah to persuade his father not to press charges, and then actually give the thief money to help turn his life around. (Also true.) According to Stanford University researchers, Salah’s arrival at Liverpool in 2017 correlated with an 18.9 percent fall in hate crimes in the city; in Egypt, his involvement in a government antidrug campaign led to a fourfold increase in help-line calls. At this point it may not surprise you that at Egypt’s last presidential elections, in 2018, there were widespread reports of voters spoiling their ballots and writing in Salah’s name, despite the seemingly pertinent fact that he wasn’t running.

Finally, some double ballroom doors swing open and here comes Salah, in a black Haculla hoodie and jeans and MGSM sneakers, being mobbed by what must be two dozen of the film crew all attempting to get a selfie with their idol. Salah goes along with it, smiling even though it’s clearly a bit much, until eventually his agent intervenes and we take refuge in another equally splendid room that appears to be set up for a wedding. Salah sits down, hands in pockets, unfazed by it all. He is used to the adoration. “It’s something I wanted,” he says. “But not that much!”

Besides, this is nothing. If he were to step out onto the street right now in Liverpool—a city that reveres its soccer players almost as much as it does the Beatles—instant mob. In New York, he can’t even stay at a hotel without some Egyptian staff member tracking down his room number and calling up to pay tribute while he’s trying to sleep. (True.) And in Egypt itself? Well, I am unable to adequately convey the extent to which Salah is beloved in his own country, where the bazaars sell his face on every marketable household item, and streets and schools are frequently renamed in his honor. “Salah is the dream,” Amr Adib, the Egyptian TV anchor who has come to interview him, tells me. “He is a role model. It is a success story: how you can begin from zero and become number one in the world.” For a country that has struggled to get back on its feet since the Arab Spring uprising over a decade ago, Salah is something more than an athlete: He has become a paragon of how to live.

Images and Article from Culture

#Salah #King #Football