You can take one look at Dune: Prophecy’s Desmond Hart, the shifty interloper who is able to set people on fire with his mind, and say that at the very least he’s not being fully honest. And regardless of his intent, you should probably be careful with how far you can trust him.

So it’s a little odd the Imperium’s emperor and empress are so game to let him off the chain in episode 2.

But this is Dune; small actions carry weight that would reverberate for thousands of years, and ultimately are informed by those same echoes. And so, their choice to throw in with Desmond Hart and his pyrokinesis speaks volumes about where the show might go with this lore — and what it might tell us about how the Bene Gesserit came to flood the universe’s power structure.

And yet, the character who tells us the most about this isn’t a member of the Bene Gesserit at all. Rather, it’s the way Empress Natalya Arat Corrino (Jodhi May) navigates around her husband that speaks to much of Dune’s themes about gender and power.

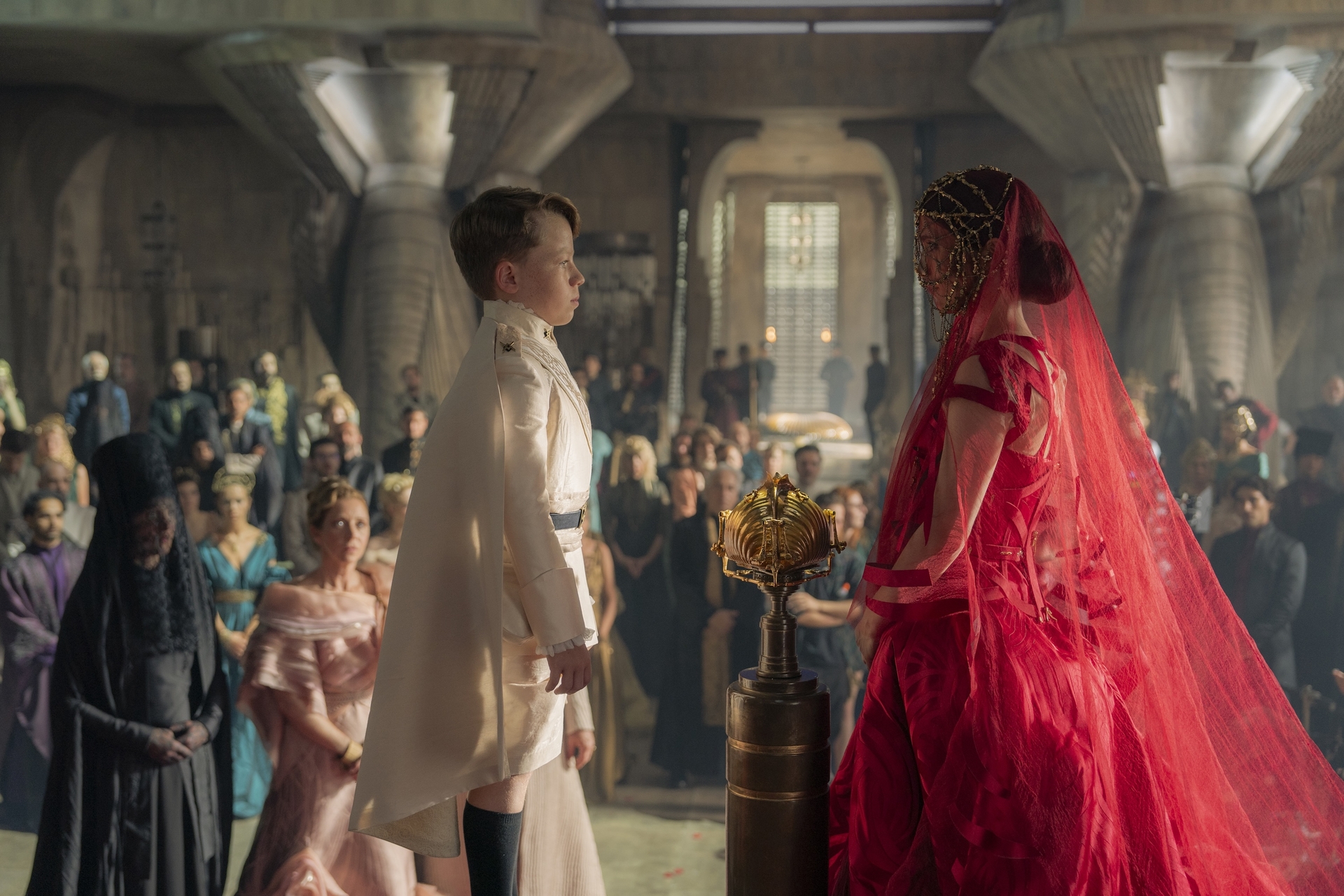

In the early episodes of the show, we see Natalya chafe against her husband’s distance from her: She pushes him to remember how it was when they ruled as a unit, insisting the Imperium was stronger because of it. She bristles at the way he relies on Reverend Mother Kasha for counsel while ignoring his wife, leaving her to simply help their daughter get prepared for the marriage ceremonies. And when he speaks to Kasha’s reasoning behind the princess’s engagement (and by proxy his own relationship), she snaps: “Stop parroting her words back at me. I know exactly what our marriage did, I brokered it.”

All this speaks to an old world that was, at least, more egalitarian than the Dune-era Imperium. By that time, the Bene Gesserit functionally run a lot of the game — as evidenced in Dune: Part Two with their manipulation of Feyd-Rautha and the emperor — but, for appearances, they’re limited to serve merely as advisors. It’s something that drives their placement of other women — like Dune: Part Two’s Princess Irulan — in advantageous marriages; all the better to manipulate. Once Paul Atreides is on the scene, they are essentially the Imperium, with the emperor at their command.

This all, of course, comes from Frank Herbert’s own old-school sense of gender dynamics when building this world. Herbert drew deep lines of gender essentialism and gender stereotypes in his universe in the early Dune books; the Bene Gesserit can only rule in a “power behind the throne” kind of way, so much so that their blueprint for the messiah is a man who can be trained in their ways. It’s the sort of choice that leaves modern adaptations doing a lot of work to thread the needle on the established lore and portray a more nuanced sense of gender and gender identity.

So Natalya’s place — both in the power structure and in opposition to the Bene Gesserit — becomes fairly telling in this regard. At a roundtable interview, May did indeed cite that she read up on medieval queens who pawned jewelry to raise tithes and armies on behalf of their husbands, women who “would have to be the power behind the throne” in preparation for playing the empress. But she also saw Natalya as rooted in a different time in the universe, one that was based on a “trust in nature,” and a return back to the “very spiritual, very instinctive” way of going about things. It’s those instincts that make her vehemently distrust anything machine-related. At the same time, it drives her to bring in Desmond Hart, despite all the unknowns about him.

“I think for Natalya what’s happened is she really feels that Javicco’s overreliance on the Sisterhood has destroyed their marriage. It’s destroyed her husband, and his capacity to be a leader, and to secure a future for their daughter,” May said. “[So] on the one hand it seems like she just sees [Hart] as a tool, and she’s being an opportunist.

“And on the other hand, he seems like someone who is, like her, an outsider. And like her, [he] has the same mistrust of the Sisterhood — and who does seem to be from this world that believes in Shai-Hulud, and is about mysticism.”

In-universe, there was a rush following the Butlerian Jihad to firmly root humanity in things that made them human. Natalya seems to represent one side of this, screaming against her would-be son-in-law’s thinking machine (aka little lizard robot), and trying to build on the human instincts inside her.

But the Bene Gesserit had a different schism, locked out of power by the emperor and banished to Wallach IX. To them, doubling down on humanity might mean leaning into hyper-femininity as a means of seizing some authority for themselves. It’s not so much that Natalya rejects their relationship to femininity, but rather that she doesn’t buy what they’re peddling — because she doesn’t need it.

After all, what we have in Valya Harkonnen (Emily Watson) is a woman who wants respect, but more than that, wants power. She sees herself and her Sisterhood as the moral arc of the universe, and will do anything to ensure they hold onto such sway. In episode 2, we see Valya check in on the Arrakis rebellion effort (for which they are playing both sides, of course) because now it’s more helpful to bolster the emperor rather than to tear him down.

And so, when all roads lead to the Sisterhood, it’s not hard to guess that maybe Natalya’s way of influence and rule might represent the old world in more ways than one. Dune: Prophecy might be about a legion of powerful women coming into their own and controlling the prognostication and truthsaying that will hold the universe in a vice grip for another 10,000 years. But the show seems to just as clearly be shaping up to be about the downfalls of that approach as well — confining power to a select group of women, and a select strategy of demure. It’s no accident that the corset Natalya wore and passed down to her daughter for her wedding is a cage.