Shared from Movies

In “Belfast,” Ciarán Hinds plays the grandfather we all wish we’d had. His Pop is a kindly soul, serving as wise, warm counsel to his grandson Buddy (Jude Hill), the impressionable hero of writer-director Kenneth Branagh’s semiautobiographical drama. Now just a few days shy of his 69th birthday — and his first Oscar nomination — Hinds is thinking back on his own grandparents.

“Not as hands-on as Ken wrote Pop,” he says over a video call from London in early February. “When I was growing up, my father was a doctor — he’d come from a working-class family and worked [his way] up to lower-middle-class, so we were removed a bit from the grandparents. But there was not a week that would go by that we wouldn’t visit them, either by car or bus. It wouldn’t be a regular [occurrence], but it was pretty regular. But we didn’t have anybody who would sit down and have the time to go over stuff with you.”

Little on this celebrated character actor’s résumé would suggest he’d be so well-suited to play the ailing but nurturing patriarch of an impoverished Protestant family in 1969 Belfast, the Troubles brewing all around them. Studying at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art before being part of the Royal Shakespeare Company and Glasgow’s Citizens Theatre, Hinds has become a mainstay of auteurist cinema, working with the likes of Paul Thomas Anderson and Martin Scorsese, often portraying somber, severe individuals. Pop presents a different side, one that’s sweeter and more elegiac, and it seems to reflect the real Hinds, who’s unfailingly modest, his voice a gentle whisper.

Judi Dench, Jude Hill and Ciarán Hinds in a scene from “Belfast.”

(Rob Youngson/Focus Features)

“Often, one is cast by the way one carries oneself — or the face one is cursed or blessed with,” Hinds notes. “Having played emperors and presidents, it’s a far cry from where I am in my spirit or soul.”

Hinds is about eight years older than Branagh, but they each grew up in Belfast. Branagh avoided advising him on how to play Pop, letting Hinds shape the character rather than imposing Branagh’s actual recollections of his grandfather on the performance. But Hinds says the script was guidance enough. The rest he took from his own family.

“I recognized in [Pop] some of the traits of my mother’s father,” says Hinds. “Especially the moments where he was working on little things out back — always doing something, fixing stuff. Then there was elements of my father — his ability to wind up the kids very easily, just to throw a little word in, and the next thing there’s doors being slammed. He’d say, ‘What did I say?,’ knowing full well what he said. [He had] that effect on people, but with a generosity and a kindness behind it.”

When Hinds discusses his upbringing, you hear the same affection for his family as Branagh’s cast brings to the fictional one in “Belfast.” That said, raised in a middle-class home, Hinds was encouraged to “get something behind you” — meaning, a proper job “for when you find out you’re never going to work in the theater.” Which explains why he initially went to college to become a lawyer, an occupation he never seriously considered.

“The truth is, at my first year at Queen’s University in Belfast, ostensibly studying law, I attended three lectures and one tutorial,” he confides with a chuckle. “I was kind of majoring in snooker and poker.” Hinds left Belfast later than Branagh — the filmmaker was 9, whereas Hinds was about 19 — but he shared with Buddy’s family a concern about how he’d be received in seemingly far-off England.

“I was very fortunate,” says Hinds. “I was going to a theater school with young students. They were very open. But I was coming from Belfast with a chip on my shoulder anyway, because of what was happening in the north of Ireland: ‘Your soldiers were all over us.’ But I [met] good English people, nice English people, who were interested and really wanted to know the issues. It seems like a small step — it was an hour’s flight to go to England — but it’s stepping off the island to a bigger island.”

He hasn’t been to his hometown much since. But he remembers going to movies as a lad — an activity that, in “Belfast,” is depicted as a magical event, one of the few instances this black and white film switches to color. For a young Hinds, cinema seemed an impossible dream. “Leaving the island and going to be trained at [the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art in London], we didn’t get any training in film whatsoever,” he says. “It was all about becoming a theater actor.”

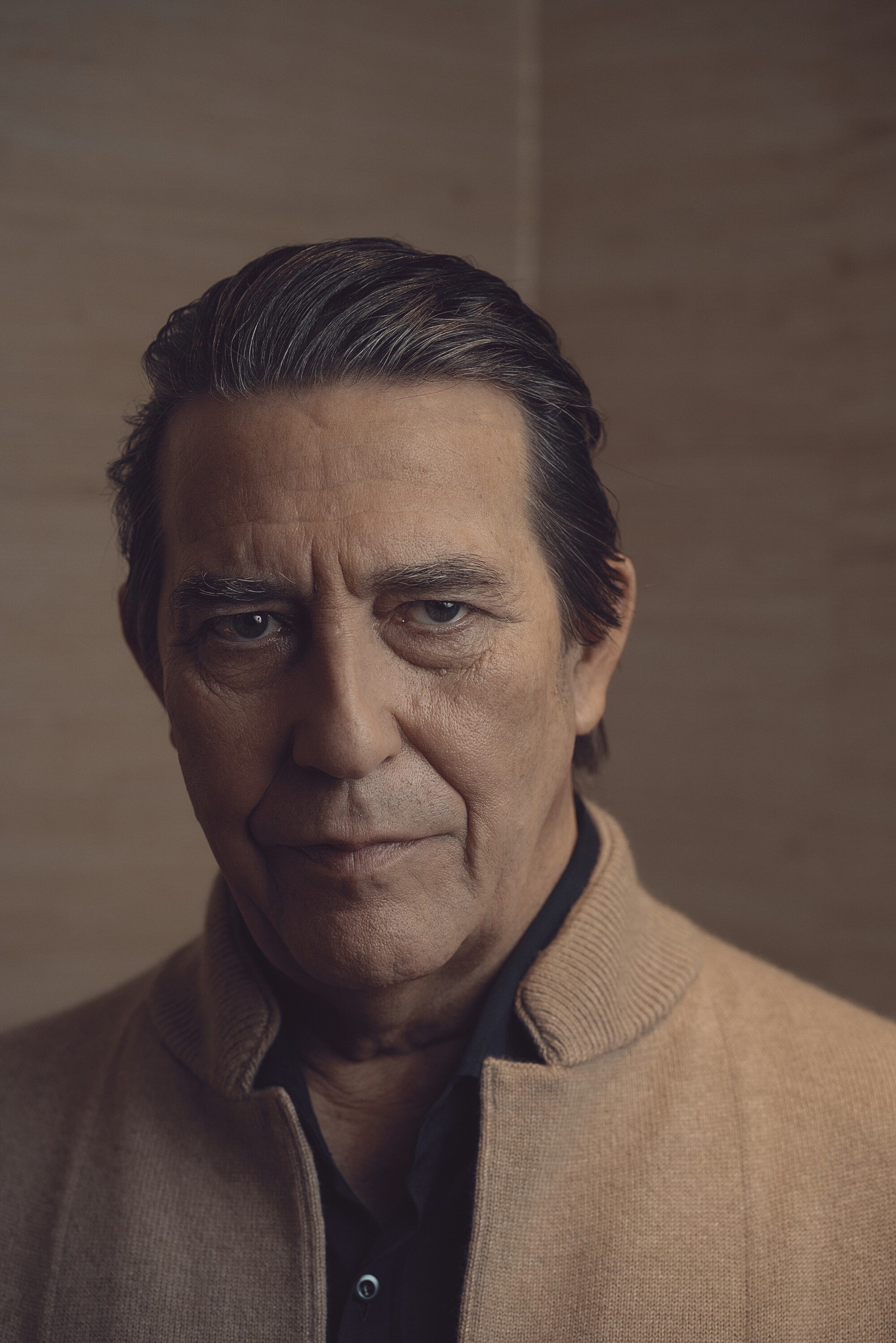

Actor Ciarán Hinds

(Tom Jamieson/For The Times)

His first movie role happened by chance. “I was in a pub. You worked without agents then — just be in the pub — somebody said, ‘Yeah, he’s an actor,’ and you got a job.”

It wasn’t just any job, though — this was for John Boorman’s “Excalibur.” “I was doing fringe theater at the time in Dublin, and I think somebody’d seen me,” Hinds recalls, almost with a shrug. “It was the look on my face he liked — medieval, or whatever it is.”

That face — timeless, weathered but capable of expressing such humanity — is a welcome sight for Buddy, who finds in his countenance a comfort during difficult times. When Hinds himself was a boy, he studied Irish dancing, a skill he shares with his young co-star Hill. Branagh thought it was kismet: As the director told Hinds, “‘He knows about discipline.’ Because, to learn the steps of Irish dancing, you’ve got to do it again and again to know where your feet go. You can’t just do it once and think you have it.”

Has such discipline been the secret to Hinds’ success?

“It didn’t help my lateness when I was younger, I’ll tell you that,” he replies, laughing. “I like to try and risk things — to get the essence down and the structure, but to try and be free. Now I realize, getting older, you need to be much better prepared, just because the old brain cells aren’t anywhere near as sharp as they used to be. But you throw it in the air to try and live in the moment.”

Images and Article from Movies