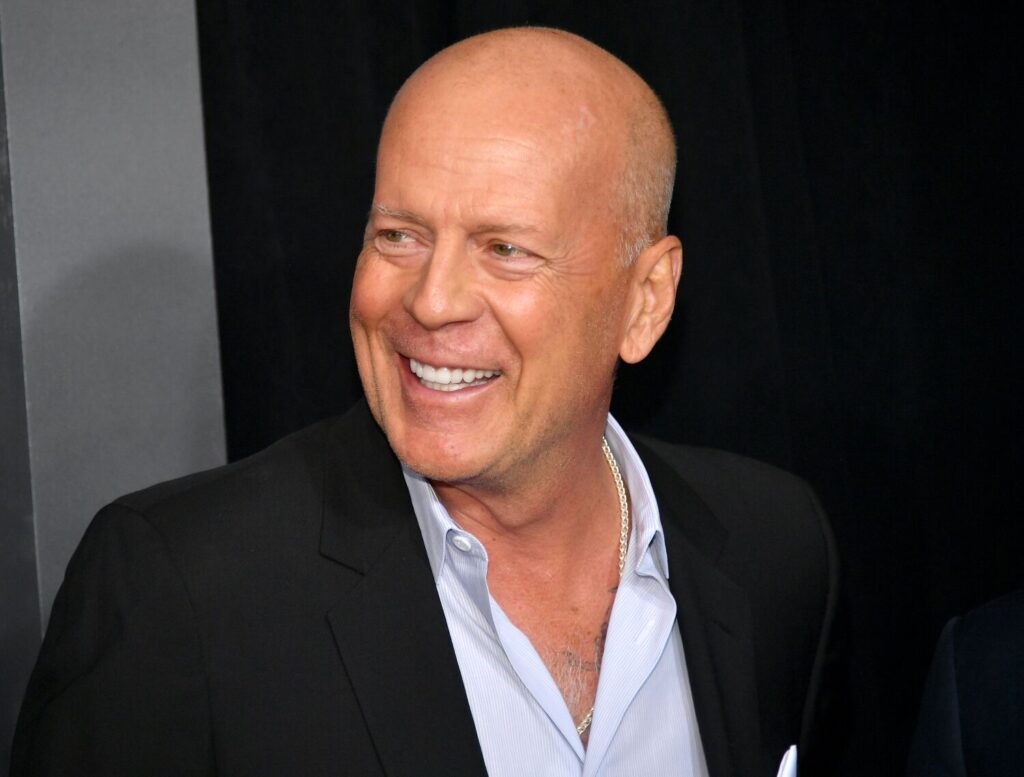

Bruce Willis, who left acting last year due to his struggles with aphasia, has been diagnosed more specifically with frontotemporal dementia, his family announced Thursday.

“Since we announced Bruce’s diagnosis of aphasia in spring 2022, Bruce’s condition has progressed and we now have a more specific diagnosis: frontotemporal dementia (known as FTD),” said the statement signed by wife Emma Heming Willis, ex-wife Demi Moore and daughters Rumer, Scout, Tallulah, Mabel and Evelyn.

“Unfortunately, challenges with communication are just one symptom of the disease Bruce faces. While this is painful, it is a relief to finally have a clear diagnosis.”

The “Die Hard” action hero’s diagnosis is sadly ominous, according to the Assn. of Frontotemporal Degeneration.

“There are currently no disease-modifying treatments for FTD; there is no cure, and no way to prevent its onset,” the association said on its website, where the Willis family’s statement was posted. “Average life expectancy is 7 to 13 years after the start of symptoms.”

The family called FTD a “cruel disease” that is the most common form of dementia for people younger than 60. “[B]ecause getting the diagnosis can take years,” the statement said, “FTD is likely much more prevalent than we know.”

“Bruce always believed in using his voice in the world to help others, and to raise awareness about important issues both publicly and privately,” the family said. “We know in our hearts that — if he could today — he would want to respond by bringing global attention and a connectedness with those who are also dealing with this debilitating disease and how it impacts so many individuals and their families.”

The frontal lobe of the brain is responsible for higher cognitive functions, including memory, emotions, problem-solving, language, judgment and more, according to Healthline, which labeled it the “control panel” of personality and the ability to communicate. It allows people to formulate speech and produce voluntary movements, including walking.

The temporal lobe is on the sides of the brain, inside the skull near near the ears and temples. This pair of areas plays a role in information-processing, memory, understanding language, management of emotions and the processing of information from a person’s senses, according to the Cleveland Clinic.

When someone has FTD, which typically hits between ages 45 and 64, the individual will commonly experience unexplained personality changes, apathy and unexplained struggles with decision-making, speaking and language comprehension, according to the Assn. of Frontotemporal Degeneration.

A hallmark symptom of FTD is anosognosia, or the inability to recognize one’s own illness, the association says on its website, noting, “People who present with anosognosia display a profound lack of insight into and emotional concern about their disease and its impact on their family members.”

There is no cure and no treatment to slow progression of FTD, though the association says some symptoms can be managed. The most common cause of death among people with FTD is pneumonia, the association says.

Prior to Willis’ new diagnosis, rumors about his work performance had been swirling in Hollywood for years before his abrupt retirement. Nearly two dozen people who had been on set with the “Moonlighting” star expressed concern to Times reporters Meg James and Amy Kaufman.

They questioned whether Willis — who was often paid $2 million for two days of work — was fully aware of his surroundings on set, according to documents viewed by The Times.

Filmmakers described the “Pulp Fiction” star grappling with his loss of mental acuity and an inability to remember dialogue. An actor who traveled with Willis would feed the star his lines through an earpiece, several sources said. Most action scenes, particularly those with choreographed gunfire, were filmed using a body double.

“After the first day of working with Bruce, I could see it firsthand and I realized that there was a bigger issue at stake here and why I had been asked to shorten his lines,” “Out of Death” director Mike Burns told The Times last year.