Who is the most successful entrepreneur in the commercial space sector? Most people would say Elon Musk, CEO of SpaceX, a company whose valuation exceeded $200 billion as of late June, per Forbes.

But New Zealand native Peter Beck belongs in the conversation. Rocket Lab, the company he founded and runs, celebrated its 50th commercial rocket launch in June, reaching that mark faster than SpaceX did. (A few days ago, it extended the streak to 51, launching an Electron rocket that deployed a low-Earth orbit satellite for a Japanese company).

If Beck commands much less of the attention economy than Musk, it has something to do with personality type.

Peter Beck on September 5, 2018 in San Francisco, California.

Kimberly White/Getty Images for TechCrunch

“I’m a natural introvert, so it’s unnatural for me to want to be ‘on show.’ And I think Elon is the inverse of that,” Beck tells Deadline. “And if you optimize for maximum attention, then it explains a lot of his decisions. At the end of the day, what I’m trying to do here is have maximum impact on the planet, and I think you’re on the planet for a period of time, and at the end of the day, the success of your time being on the planet is judged by how much impact did you have to the number of people you could. So, I’m not optimizing for attention, I’m optimizing for that.”

Courtesy of HBO

Beck steps out of the introvert’s natural comfort zone to “star” in the new HBO documentary Wild Wild Space. The film directed by Ross Kauffman examines the remarkable mix of minds trying to give Musk and some of his fellow space-obsessed billionaires a run for their money.

“We are never going to outspend Elon Musk. We’re not going to outspend Richard Branson and we’re not going to outspend Jeff Bezos, and these are our competition,” Beck notes. “The only way you win is you have to outthink. And sometimes when you don’t have the resources, you have to come up with more innovative ideas.”

Among Rocket Lab’s innovative ideas is developing the Neutron rocket, a 131-foot-tall colossus that will support big payloads and human space travel beyond Earth’s orbit. It’s designed as a direct competitor to SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rocket. Rocket Lab, despite its name, sees itself as a good deal more than “just” a rocket maker. Last year, it won a half-billion-dollar contract from the U.S. Space Development Agency to build 18 spacecraft as part of a constellation of military satellites.

Rocket Lab

“What we are trying to build here at Rocket Lab is something really unique. We’re trying to build an end end-to-end space company,” Beck explains. “If you look at the really large space companies of the future, they’re not going to be just a launch company or just a satellite company. They’re going to be a company that provides a service to a person, a government, or a corporation. And that’s where we’re driving to at the fastest pace we can.”

As seen in Wild Wild Space, Beck accomplished all he has without the benefit or need of a college education. He was raised in Invercargill, New Zealand in middle class surroundings (unlike Musk, who grew up in great wealth).

Peter Beck receives the “Ernst & Young Entrepreneur of the Year” award for New Zealand on June 10, 2017 in Monte Carlo, Monaco.

Toni Anne Barson/Getty Images

“I was lucky that I knew exactly what I wanted to do from the youngest time I could remember and that was I wanted to work on rockets, and I wanted to work in space,” he recalls. “And the original plan was to go and work for NASA, but as an engineer with no degree and a foreign national, that wasn’t feasible. So, the only logical solution here was to just do it myself.”

If not for the encouragement of his mom, a teacher, and his dad, a museum director, he might have ended up with a rather more mundane occupation.

“I remember when I was at high school, the local school called in my parents for a family meeting with the careers advisor because the careers advisor felt that my aspirations were totally unrealistic and that I should go and work in the local aluminum smelter as a welder,” he says. “I was just lucky that I had parents that there was no ceiling placed on your ambitions.”

Wild Wild Space explores how SpaceX has become critical to America’s defense as a major Pentagon contractor (it landed a $1.8B contract “for a powerful new spy system with hundreds of satellites bearing Earth-imaging capabilities,” according to a Reuters report earlier this year). As such, Musk exerts considerable sway over American foreign policy, and has inserted himself into geopolitics by dictating certain terms under which his Starlink satellite system can be used. Is it healthy for the world’s richest person (a man often branded by critics as a megalomaniac) to have acquired that much influence? Beck hesitates to tee off on Musk but does offer a measured assessment.

“I think the obvious is true is that anybody that wields kind of [an] unwieldy amount of power, sometimes it comes off for the best and sometimes it comes off for the worst,” he observes. “I think in my industry, what’s become fairly obvious is it has been described as an accidental monopoly. And I can assure you there’s no accident about it. And that is fine. He is a very, very tough businessman and that’s fine, but I don’t know any monopoly that has survived the test of time. And so at least in part what we’re trying to do with our big Neutron rocket is to bring some balance to the system. And there’s a lot of people and a lot of customers that are very happy to see that happen.”

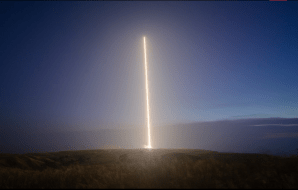

A SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket, loaded with Starlink communications satellites and launched from Vandenberg Space Force Base, heads for orbit on July 10, 2024, as viewed near Lompoc, California.

George Rose/Getty Images

Musk’s SpaceX suffered a rare setback in July when a Falcon 9 rocket failed to properly deploy a satellite. The company says it traced the cause to “a crack in a sense line for a pressure sensor attached to the vehicle’s oxygen system.” Another argument, perhaps, for not leaving the commercial rocket business to one company alone. Another lesson that can be drawn from that failed SpaceX mission? It’s extremely challenging to launch a rocket, whether you’re SpaceX or Rocket Lab.

RocketLab CEO Peter Beck poses for a portrait at the company’s Auckland facilities on June 10, 2015 in Auckland, New Zealand.

Phil Walter/Getty Images

“Every day we get up and we go to work and we battle with physics. And that’s just the nature of the job. Somewhere between 1 and 3 percent of the total weight of the rocket is actually the payload that you lift. A rocket is like 92 percent fuel, 2 or 3 percent payload, and the rest is structure. And fundamentally it’s just really freaking hard to do and there is zero margin for error,” says Beck. “There’s just incredibly fine safety margins. You’re in an incredibly harsh environment and everything has to be 100 percent perfect 100 percent of the time, and that’s really hard to do.”