As the diesel-fuelled generator pumps CO2 and toxic fumes into the air, Chris and Katherine Singer’s children kick a football not far from the exhaust. This is daily life for Chris and his family, who own a 486-hectare (1,200-acre) farm, and for the other 14 homes in the upper Coquet valley in Northumberland national park. The noisy generator and toxic fumes are in stark contrast to the tranquil and picturesque hills of one of the most beautiful landscapes in the UK.

“All we want is the same electric utility that the rest of the UK take for granted,” Katherine Singer, who looks after 1,100 sheep, says.

In the 1950s, it was deemed too expensive to connect the area to the mains. Now, a proposal to get mains electricity to the farms and homes of the valley stands a chance of going ahead.

-

Chris Singer services his generator, a task that should be done every 300 hours. Oil changes and filter changes are common, with a full rebuild needed every two to three years.

-

Harry Byatt, 39, services his generator. Even if the valley gets mains electricity, Harry’s farm is too far away, and will not be included.

No house in the valley has phone reception and all depend on outdated and unreliable generators. But the community’s generators, with annual running costs of £7,500 each, often fail.

Simply using hair straighteners and a washing machine at the same time can be enough to overload the antiquated engines, say the local people.

Each generator burns through approximately 8,000 litres of polluting diesel a year. The CO2 emission from one litre alone is 2.68kg and the toxic emissions contain more than 40 air contaminants.

-

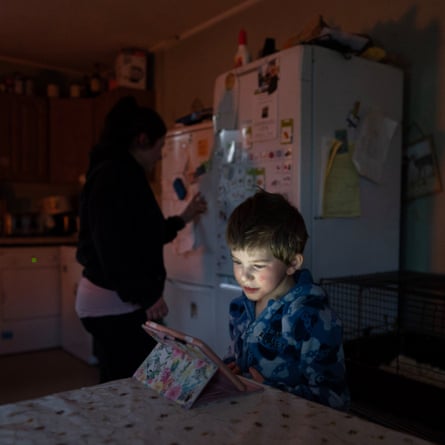

Riley Day, 8, watches his iPad in the kitchen. Riley is autistic and is heavily dependent on the internet and electricity to communicate, a lifeline for what can be a very difficult situation.

-

Riley in the kitchen (left). Harry Day, 12, speaks with other players online as he plays on his video game. His mother, Laura, says that as they are so remote, and so far away from anyone, using video games is an important form of communication for him.

“I feel like this is the forgotten valley,” says 30-year-old sheep farmer Laura Day. Her son Riley, aged 8, is autistic and heavily dependent on the internet and electricity to communicate, a lifeline for what can be a very difficult situation. If the generator cuts out it can be a race to get it back running again before Riley starts thrashing, when he can end up hurting himself.

Her other son, Harry, 12, uses online gaming to communicate with his friends. “It’s not as if he can just pop down the road and see his mates, so the games are an important part for his communication with others,” Laura says.

It is worth pointing out that given the surrounding location alternative forms of energy are not an option. There is not enough sun for solar energy given the long winter months, low-flying aircraft over the MoD land and military ranges rule out wind farms and hydro-power is unfeasible because many of the riverbanks are sites of special scientific interest (SSSI).

The head of conservation and environment for Northumberland national park issued a 16-page rejection letter to the valley’s application to secure mains electricity. Their reasons among others were the unavoidable 7.5 miles (12km) of overhead lines and light pollution of the night sky.

But local walker Jason Seymour, 38, said: “People who come out here aren’t going to be concerned about a few poles. Plus, I don’t think the light pollution will be a problem, the houses already use electricity from their generators, and each house is about a mile apart from each other.”

The houses and farms rely on electricity just as much as anyone else in the modern world, if not more due to farming practices such as lambing: the 24-hour a day, six-week period where sheep provide them with the next generation. The heat lamps and farm lights provide a salvation, and an ability to keep the farm operating.

-

Newborn lambs, rejected by their mothers, use the heat lamp to stay warm as they gather their strength. The heat lamps run on electricity from the generator and need to be constantly on. Katherine Singer watched the sheep in the lambing shed through a newly installed camera. This is another example of their dependency upon constant electricity and internet access in order to look after their livestock.

Not only do the farmers rely on the constant supply of electricity but the younger ones of the valley often use the internet for communication and even education. Without a mobile phone signal they use BT phone lines supplying internet speeds of approximately 0.76 Mbps. Some houses in the upper end of the valley don’t even have the privilege of the BT lines, so have to rely on a satellite dish for their internet, costing £76.00 a month.

-

William Wood, 15, getting ready for an online maths tutorial at his home. His mum, Sam has to make sure every other device such as Sky and the smart TV are switched off to ensure a better internet connection.

With internet as bad as this online education is near impossible, so the children still make their way to school every morning, having to take a taxi and two buses to get there, taking an hour and a half each way.

In defiance of the 16-page rejection letter the Northumberland county councillor for the area, Steven Bridgett, along with residents of the valley, attended an extraordinary meeting with Northumberland national park authority, where he made a passionate five-minute speech to the members of the authority as they then decided to either to object to the proposal, something that would keep the upper Coquet valley in the dark, or register “no objection”, which would take the valley one step closer to an easier, brighter and greener future.

-

A relieved Katherine Singer and other residents outside Northumberland national park offices after national park members to decided to make no objection to the application for mains electricity, taking the valley one step closer to an easier, brighter and greener future. The decision now lies with the secretary of state, Grant Shapps, and is the closest the valley has ever been to getting mains electricity.

-

Left: the proposed route of power lines is displayed on a map at Northumberland national park offices during the meeting with national park authority members to decide the potential future of the upper Coquet valley and its chance of getting mains electricity. Right: members of the Northumberland national park authority vote “no objection” to the application for mains electricity, taking the valley one step closer to an easier, brighter and greener future.

The outcome was “no objection”, which means it is now in the hands of Grant Shapps, the secretary of state for energy security and net zero.

But even if he does give the green light, there will always be one house left out, at the top of the valley.

Meghan Byatt, 39, would need her own substation to get power to her, but she says: “Everyone is in support of this. Even me!”

For now, her house, along with the others in this part of Northumberland, will remain in the dark.