Director Sarah Friedland knew she wanted to set her debut feature, “Familiar Touch,” in Los Angeles. The decision was, in part, personal — both her grandmothers lived in the city — but also thematic. “Familiar Touch” is about an aging woman, Ruth (Kathleen Chalfant), dealing with memory loss.

“I didn’t want the viewer to have a sense of time passing that Ruth doesn’t,” 33-year-old Friedland tells me at the film’s publicity office on a gray New York day. “So it needed to be somewhere where you couldn’t tell that there was seasonal change.”

But Friedland, who was born in Los Angeles but grew up in Santa Barbara, also had another goal in mind. She wanted to shoot in a real senior living community where the residents could participate in the production.

Friedland ended up making “Familiar Touch” (in theaters Friday) at Pasadena’s Villa Gardens in a unique collaboration with both the staff and denizens. Before her 15-day shoot, she and her team held a five-week workshop on filmmaking for Villa Gardens’ seniors, who later became background actors and production assistants on the project. It was an example of Friedland essentially putting her money where her mouth was.

“It came a lot from the anti-ageist ideas of the project,” Friedland says. “If we’re going to make this film the character study of an older woman that sees older adults as valuable and talented and capacious, let’s engage their capaciousness and their creativity on all sides of production.”

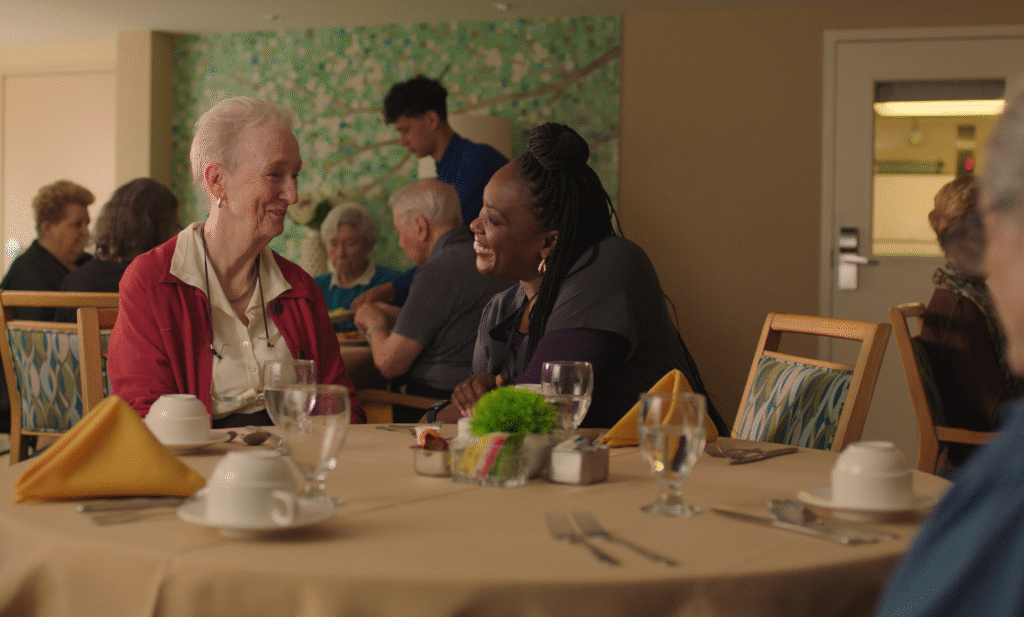

Kathleen Chalfant, left, and Carolyn Michelle in the movie “Familiar Touch.”

(Music Box)

Friedland, whose background is in choreography, wrote the screenplay inspired by her own experience as a caregiver to artists with dementia. In the film, Ruth is disoriented when her son (H. Jon Benjamin), whom she does not recognize, moves her into a senior living home. Ruth does not see herself as elderly, instead making her way to the kitchen and working alongside the staff. That’s where she is comfortable, having spent years as a cook.

In order to find her perfect setting, Friedland started researching just as if she were a child of older adults looking to move her parents. She heard about Villa Gardens from the sister of her own grandmother‘s caregiver, and it was exactly what she wanted: a place with the resources to accommodate her crew that felt appropriate for the story she was trying to tell. In her mind, the community in her fictional story should be one of privilege, a circumstance in which Ruth, who grew up in a working-class Yiddish family, could initially feel ill at ease.

The history of Villa Gardens also was appealing. It was founded in 1933 by Ethel Percy Andrus, who also started the AARP and was California’s first female high school principal.

“It’s a community that draws a lot of retired educators and social workers,” Friedland says. “So there’s this culture of lifelong learning.”

Before Friedland could move in, however, she had to prove herself. Villa Gardens executive director Shaun Rushforth turned her down four times before saying yes. Having worked at Kingsley Manor in East Hollywood — another senior living community which is often used as a location thanks to its handsome brick facade — he was skeptical of inviting the crew.

“Small independent films were the ones I’d had the worst experiences with,” Rushforth says. “I wasn’t sure how this was going to fly with the residents.”

Director Sarah Friedland, right, works with a Villa Gardens resident while filming “Familiar Touch.”

(Music Box Films)

Still, every time Rushforth thought he was going to give Friedland a strong no, it ended up being a “soft no,” he remembers. Eventually, she won him over with her commitment to telling an authentic story. With that pledge in place, Rushforth gave her a final test: She had to convince the residents. Lisa Tanahashi, 68, a resident who ended up assisting the “Familiar Touch” art department, was happy Rushforth gave Friedland a hard time.

“I feel bad that Shaun always has to say that he turned her down four times,” she says on a joint Zoom call from Villa Gardens with Rushforth. “And yet from my perspective, that’s exactly what we residents want him to do.”

Jean Owen, 87, who was the elected president of the residents’ association at the time, was immediately impressed by Friedland and the narrative she wanted to tell.

“We need more information about senior living,” she says in a video call from her apartment at Villa Gardens, her face hovering at the bottom of the frame. “We need more information about dementia or Alzheimer’s or whatever we call it — anything that can give it a good spin, not a negative, because we’re all aging.”

Owen, like Tanahashi, signed up for Friedland’s twice-a-week workshops, where she learned about cinematography and production design from “Familiar Touch” department heads who were patient in their teachings.

“We’re not easy,” Owen says. “We don’t mean not to be, but there’s just something about the aging process that it takes a little longer to catch on. She made us feel so comfortable. They all did.”

Villa Gardens residents Jean Owen, left, and Ann Graf discuss a scene in front of a camera.

(Sarah Friedland)

Once the workshops concluded, the participants could then decide what department they wanted to contribute to during the actual filming. Owen helped cast background actors for scenes. She says she received very little pushback from her fellow residents. Only two complained.

“One man said he had better things to do for four hours than to sit at a table with stale food,” she says. “And the other woman complained because in her scene, which was a dining scene, they kept serving the same food and it was cold.”

(Friedland confirms this gripe: “The scrambled eggs being cold was the main point of complaint.”)

Friedland worked with Rushforth and other members of the staff so that the filming wouldn’t interrupt the daily rhythms of life at Villa Gardens. Caregiver Magali Galvez, who has worked at Villa Gardens for around 20 years, fielded questions from “Familiar Touch” actor Carolyn Michelle, who plays the woman who assists Ruth.

Although Ruth is supposed to be in a memory care unit, the production did not collaborate with those receiving similar treatment because Friedland believed they would not be able to give consent to be on camera. Ultimately, close to 30 Villa Gardens employees worked on “Familiar Touch,” along with 80 residents.

The movie’s 80-year-old star, Chalfant, who shot the film when she was 78, saw the people living at Villa Gardens as her peers.

“We’re all old people,” she says. “The oldest person in the crew was in their middle-30s. In an odd way, that was a kind of division and also a collaboration between old people and young people. There wasn’t any hierarchy.”

One issue Friedland had directing the non-professional actors was that they often became entranced with Chalfant’s performance.

“Kathy’s such a magnetic performer that there were some residents who would start out playing their background role, and then Kathy would start her dialogue, and they were mesmerized and watching her,” Friedland says.

One sequence where Chalfant was supposed to be floating alone in the pool drew crowds of residents watching through windows. Meanwhile, the video village, where a director typically watches playback footage on screens, was perpetually crowded. “Video village was a village,” Friedland says.

Jean Owen, president emeritus of the Villa Gardens Residents Council, poses with the Venice Film Festival awards won by “Familiar Touch.”

(Gabe Elder)

But the participation also kept the filmmakers honest. Through working with the Villa Gardens community members, Friedland strove to inject humor into the film based on what she observed. A moment where Ruth sees a woman wearing a potato chip clip as a hair adornment captures that atmosphere.

“The residents, when I pitched the film — one of the first things they said was that this film can’t be too depressing,” she recalls. “There’s so much humor in our daily lives. This has to capture that sense of humor, but we can’t be laughing at them — we have to be laughing with them, and it has to be absurd and uncanny.”

Watching the final product has been a bittersweet experience for those from Villa Gardens, who both are thrilled to see themselves on screen but recognize that some of their fellow castmates have since died.

“It’s wonderful to see them real again,” Owen says, also noting that she found the portrayal of the onset of dementia true to life.

Many saw the film for the first time during its AFI Fest premiere at the TCL Chinese Theatre, a screening that Friedland says gave her more nerves than the movie’s debut at last year’s Venice Film Festival, where it won the prestigious Lion of the Future award, as well as prizes for directing and acting.

“The residents and staff put so much work into this, and I wanted to do them proud,” Friedland says. “But it was so joyous.”

The day after the Chinese Theatre screening, Friedland brought the film to Villa Gardens for those who couldn’t make it to Hollywood. She also brought along the Lion statues the team won in Venice and got the festival to send an extra award certificate to give to the community. It is going to live in the Villa Gardens library, forever connecting the place to its cinematic history.

Content shared from www.latimes.com.